BICENTENNIAL 2018: Saukenuk was once home to Black Hawk and more than 6,000 Sauk

By Roger Ruthhart — October 26, 2018

This statue of the warrior Black Hawk looks out over the Rock River Valley from a perch next to the lodge at Black Hawk State Historic Site in Rock Island. (Dispatch-Argus photo by Terry Herbig)

Saukenuk was well-known as one of the largest Native American villages in North America, but one of its residents, the warrior Black Hawk, was even better known.

Although born in Saukenuk, which was located where Rock Island stands today, his father Pyesa and mother Summer Rain and other relatives could trace their ancestry back thousands of years. According to their oral traditions, both the Sauk and Meskwaki tribes were living in Canada 12,000 years ago at the time of the last glacial retreat. Many centuries later they were displaced from their Canadian home by the Iroquois.

The Sauk and Meskwaki migrated through New England and New York to the area near Niagara Falls. By 1640, the Meskwaki had settled at the west end of Lake Erie, near present-day Detroit, and the Sauk near Saginaw Bay in Michigan.

In 1701, the decades-long war began between the French and the Meskwaki, which almost led to the tribe’s extinction. Weakened, they joined the Sauk and together they migrated to the Mississippi River, where for nearly 100 years the tribes lived in their own villages and farmed, hunted and traded.

The two tribes were separate nations. The Meskwaki were the smaller of the two, numbering about 1,600. In Rock Island, the Meskwaki had a village located across from Arsenal Island in what is now downtown Rock Island. In the days before the locks and dams, the river was 17 feet lower than today. Fort Armstrong loomed 30 feet above the river, according to Beth Carvey, retired historian at the Black Hawk State Historic Site.

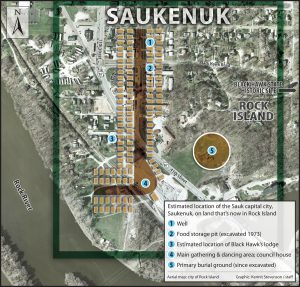

Over the years, the Sauk had several cities called Saukenuk. In 1808, the decision was made by the Sauk nation to consolidate smaller villages into the city now known as Saukenuk, located near the Rock River in Rock Island. Its location is near the Black Hawk State Historic Site, home to the John Hauberg Indian Museum which commemorates the lifestyle of those who lived at Saukenuk.

According to Ferrell Anderson, a local archaeologist, the Meskwaki village was made up of two rows of huts – about 30 total – located where downtown Rock Island is today.

Antoine LeClaire, an early area settler, Illinois Gov. John Reynolds and Gen. Winfield Scott, at the table, are depicted in this mural of the signing of Black Hawk Purchase Treaty of 1832. Agreed to in the wake of the Black Hawk War, the sale conveyed Sauk lands in Iowa to the United States. (Photo courtesy of Rock Island Arsenal Museum)

In 1824, Thomas Forsyth, the Indian agent at Rock Island, wrote a report detailing the Indian villages within his jurisdiction.

Two miles up from the mouth of the Rock River was the “grand Sauk village where the principal chiefs, braves and warriors reside, … and where all the affairs pertaining to the Sauk Nation of Indians were transacted,” Forsyth wrote. “Indeed, I have seen many Indian villages, but I never saw such a large one or such a populous one.”

Behind the town, on the side of the ridge, were the Sauk gardens which Black Hawk indicated extended about 2 miles. Forsyth estimated the Sauk had about 800 acres under cultivation.

Saukenuk had a north-south and an east-west esplanade that formed a “T.” The east-west road was defined by the river and the bluffs. It intersected with a longer north-south avenue that was lined with many lodges. At one end was a gathering area and the council lodge. We know there were as many as 100 or more lodges at one point, and Saukenuk was home to as many as 6,000 – perhaps more.

For most of the years that the Sauk and Meskwaki lived on these lands, their life was an idyllic one. They lived peacefully in their villages with occasional skirmishes with other Indian tribes. They traded with the French and fought alongside the British, providing a lifestyle that was partially Indian and partially European.

The Sauk lived what might be described as an affluent lifestyle by Indian standards. Many of the Sauk dressed in European clothes and hunted with rifles. When they did use arrows, they had metal tips, not stone. Their village on the shore of the Rock River was a thriving metropolis during the summer. In fall, crops from their farms were stored in food pits and they crossed the river and wintered in southern Iowa and Missouri – returning to Saukenuk in the spring.

Unknowingly, the end of this lifestyle had been assured in 1804 when a few chiefs – possibly plied with alcohol – signed a treaty in St. Louis in which they agreed to move west of the Mississippi River in exchange for $1,000 a year, at such time as settlers arrived seeking to live on the land.

In 1830 the Sauk and Fox were ordered to leave their villages in Illinois and move to Iowa. Black Hawk and others refused to accept the terms of the 1804 treaty that the Sauk and Meskwaki had not been involved with.

In the winter of 1830, the tribes left but faced a winter of near starvation. In spring 1831, Black Hawk defied the government order and returned to Saukenuk and planted crops.

The settlers who had now occupied the old village were alarmed. Illinois Gov. John Reynolds sent 1,500 men to move the tribes out. On June 20 the volunteer army moved on Saukenuk.

This overlay map of south Rock Island shows the Sauk village of Saukenuk covered a good portion of a residential area of present-day Rock Island. (Dispatch-Argus graphic by Kermit Stevenson)

When the militia arrived at Saukenuk, they found fresh footprints and fires still burning. The Sauk had left without a fight. The militia burned the lodges, destroyed the crops and vandalized the main cemetery and dug up graves, according to a letter from the new Indian agent, Felix St. Vrain, to Indian superintendent William Clark.

Fearing he would be pursued, Black Hawk went to Fort Armstrong and sued for peace. He got it, under the terms that he would stay out of Illinois.

Peace lasted until the next winter when the Indians, unable to grow crops in the less tillable land, once again faced starvation. In 1832 the Indians again crossed into Illinois, marking the second year of the Black Hawk War.

There were numerous skirmishes and Black Hawk’s people, on the verge of starvation, fled into Wisconsin. They were finally trapped at Bad Axe Creek where they were slaughtered. Black Hawk and other leaders were captured and the militia killed old men, women and children, as well as 150 braves.

“When I call to mind the scenes of my youth and those of later days – and reflect that the theatre on which these were acted had been so long the home of my fathers, who now slept on the hills around it, I could not bring my mind to consent to leave this country … for any earthly consideration,” Black Hawk wrote in his autobiography.

Roger Ruthhart is former editor of The Dispatch-The Rock Island Argus.

Editor’s note: The weekly Illinois Bicentennial series is brought to you by the Illinois Associated Press Media Editors and Illinois Press Association. More than 20 newspapers are creating stories about the state’s history, places and key moments in advance of the Bicentennial on Dec. 3, 2018. Stories published up to this date can be found at 200illinois.com.

–BICENTENNIAL 2018: Saukenuk was once home to Black Hawk and more than 6,000 Sauk–