New school discipline rules to start statewide

By Jean Lotus Staff Reporter — July 12, 2016

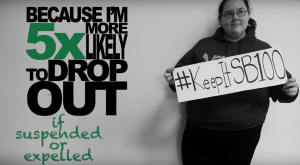

A student holds a promotional sign for SB 100 in a video released by Chicago Public Schools student group Voices Of Youth in Chicago Education (VOYCE).

Changes in school district disciplinary procedures coming this fall around the state will seek to reduce the number of student suspensions and expulsions.

SB 100, signed last summer by Gov. Bruce Rauner, will provide a framework for districts to develop their own school discipline policies, filed with the Illinois State Board of Education. The new law, which takes effect Sept. 15, aims to reduce the number of suspensions and expulsions in Illinois schools, and make out-of-school discipline measures the “option of last resort” after other procedures have been exhausted.

“We need SB 100 because I was fined a dollar for every stick of gum I had in my backpack when I was in middle school,” said CPS graduate Jaime Adams at a Springfield press conference. “I know students who were suspended or expelled for minor offenses like not sitting down on a chair, or using their phones in class. These policies are unfair, don’t change behavior and don’t help students learn,” she said.

Reacting to 2011 data showing that Illinois African-American students were suspended or expelled from school at the highest rate in the U.S., an educational task force, including State Sen. Kimberly Lightford (D-Maywood), worked for years to hammer out a proposal that protected students but gave school districts autonomy.

“What we found was that some districts are doing a good job, but many others were not,” Lightford said. A 2013 version of the bill was shot down by school administrators and law enforcement groups.

The new law gets rid of “zero tolerance” discipline policies unless the student can be shown to be a danger to others. It also requires schools to seek in-school discipline options, if possible, and to give written reasons for discipline measures.

Students who are asked to leave school are allowed to complete homework, and districts are required to check in with students when exiting and returning to school. The new rules also forbid fines for discipline infractions, and forbid counselors from encouraging students to drop out after a long absence from school, a practice known as “counseling out.”

In 2011-12, data from the U.S. Dept. of Education brought racial disparities in school discipline to light nationwide. For the first time, the department’s Civil Right Data Collection project collected discipline data from every school district in the country instead of just a sample.

Soon, researchers were making interesting findings: Illinois had the highest suspension rate in the country of African Americans (25 percent) according to a study by the UCLA Civil Rights Project.

“Zero tolerance” policies came into vogue after the 1999 Columbine shootings, Lightford said, and were originally used for students who brought weapons to school. But over time, “those policies were beginning to be misused,” Lightford said. In Illinois, suspensions between three and 10 days long were adding up to more than 1.2 million hours of instructional time lost in the 2010-11 school year. Often these suspensions were the result of “minor infractions,” she said.

Members of the Chicago Public Schools student group Voices Of Youth in Chicago Education wait in Springfield as lawmakers discuss Senate Bill 100 on June 28. (Photo courtesy VOYCE Facebook)

Research provided by Chicago Public Schools student group Voices Of Youth in Chicago Education (VOYCE) was the foundation on which SB 100 was built, Lightford said.

“VOYCE was on the front lines of pushing [SB 100],” Lightford said.

Data analyzed by VOYCE in 2011 showed Chicago Public Schools suspended around 89,300 students a year in 2009-10. Of those about 25,500 were in high school. Minority students were much more likely to be suspended or expelled. In the 2012-13 school year, Chicago Public Schools issued 32 out-of-school suspensions for every 100 black students, compared to just five for every 100 white students, data showed.

“Multiple research sources [conclude] that harsh discipline policies are highly overused in Chicago, keeping students out of valuable learning time, decreasing students’ chances of graduating, and costing the city millions of dollars,” said VOYCE in a report. “Harsh discipline policies at CPS have negatively impacted school safety and student achievement, at a huge cost to taxpayers.”

A culture of metal detectors, in-school police officers did not make students feel safe and interfered with student achievement, according to VOYCE. Along with the University of Chicago Consortium on Education, researchers found that “Inside the school building, the mutually supportive relationships that parents and students have with teachers are the most critical elements defining school safety.”

VOYCE said the passing of SB 100 was a giant step in the “decriminalization of children of color.”

Students who are suspended or expelled are three times more likely to have a run-in with the law, five times more likely to drop out and six times more likely to repeat a grade, the group said. Additionally, almost 20 percent of school expulsions in Illinois are given to students with special needs.

Lightford said members of the education task force found Chicago was the tip of the iceberg. The task force found many districts in Illinois had high suspension rates. For example, there were 47 out-of-school suspensions for every 100 students in Thornton Township HSD 205 (South Holland), 36 for every 100 in Proviso Township HSD 209 (Forest Park), and 30 per 100 in Thornton Township HSD 215 (Calumet City). School discipline policies varied widely all across the state, the task force found. Data showed minority children were being suspended at a significantly higher rate statewide.

The changes are in part a response to educational research showing that student exclusion isn’t the best motivator.

Sometimes teachers and principals have to explain new research to school boards.

In 2015, Lyons Elementary District 103 George Washington Middle School Principal Paul Bleuher faced skepticism from the board when he closed a “time-out” room that was used by teachers to remove students from class.

“Positive behavior relationships begin in the classroom,” Blueher told the board. “If discipline happens down the hall, that gives the power to someone else other than the teacher,” he said.

“Current research and best practices has proven zero-tolerance and punitive measures don’t work. They’re just not effective,” Bleuher said. “Some students are dealing with extremely challenging life situations. There are better ways to deal with that.”

Schools were given an extra school year to overhaul, or create a discipline policy.

“They will have one [discipline] policy, available on request, to level the playing field across the state,” Lightford said.

Chief sponsor in the Illinois House Rep. Will Davis (D-Harvey) said SB 100 “allows schools to maintain control, while providing guidelines for schools to follow so that our students remain in school and on track to graduate.”

Read the current issue of the Cook County Chronicle

Free digital subscription to the Cook County Chronicle

— New school discipline rules to start statewide —