Advocates tout economic benefits of renewable energy

By Jerry Nowicki Capitol News Illinois — December 9, 2020

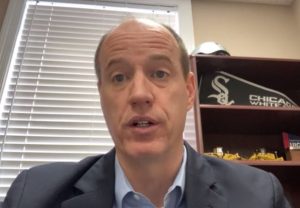

State Sen. Bill Cunningham, D-Chicago, speaks at a virtual news conference Tuesday, Dec. 8 in support of the Path to 100 Act to fund renewable energy investment in Illinois. (Blueroomstream.com)

SPRINGFIELD – While advocates in Illinois were optimistic that a series of measures reforming the state’s energy landscape could pass in 2019, various factors caused the legislative package to stall while most of Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s first-year agenda eventually became law.

At the time, advocates behind the Path to 100 Act warned of an impending “funding cliff” for renewable energy projects if the General Assembly did not act to increase the rate cap on ratepayer bills, which is the funding source of the renewable energy fund overseen by the Illinois Power Agency.

Now, amid a backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, an ongoing scandal ensnaring the state’s largest utility and a potential upheaval of leadership in the state House, the lawmakers pushing for that bill say the funding cliff has arrived.

“The Illinois Power Agency announced the close of the state renewable energy incentives for residents in central and southern Illinois just this last week (on Friday, Dec. 4) and incentives in Chicago and the rest of Northern Illinois are going to be gone in a matter of weeks as well,” state Sen. Bill Cunningham, D-Chicago, said in a virtual news conference Tuesday, Dec. 8. “This is a problem we’ve been talking about for years and we’ve been predicting and it’s here now. Without new legislation, renewable energy programs will be shut down, it’s going to be shut down for years to come.”

There are solar and wind projects with existing commitments from the Illinois Power Agency that will continue to be funded, but applicants for new incentives will be waitlisted indefinitely.

Dawn Heid, who is CEO of the residential solar panel installation company Rethink Electric, said that’s going to mean layoffs for her sales force as the waitlist grows. Her installation crews, she said, will likely be employed through April 2021 as they finish installations for projects with currently committed funding.

“Beyond that we do not have any revenue sources coming in from renewable energy,” Heid said.

The fund overseen by the Illinois Power Agency is replenished through a charge on the supply portion of ratepayer electric bills, which is currently capped at about 2 percent. The Path to 100 Act would lift that cap to 4 percent over a period of years, allowing for more money in the fund to be granted for new investments in wind and solar energy.

Illinois State University economics professor David Loomis estimated the impact of passing the Path to 100 Act would number in the billions of dollars from 2021 to 2033.

He authored a report showing the legislation would create or support 53,298 jobs during construction periods and 3,215 jobs during operations. That would create $8.27 billion in increased economic output during construction and $571 million per year in increased economic output during operations, per the report.

Rep. Will Davis, a Hazel Crest Democrat and the bill’s House sponsor, also noted the report showed existing renewable energy projects have generated $306 million in local property taxes, including $41.4 million paid out in 2019.

“As a firm advocate for school funding and knowing that a lot of local school funding is derived from property taxes, these resources are going to go a long way,” Davis said.

According to Davis, part of the purpose of the virtual news conference Tuesday, Dec. 8 was to build support for the Path to 100 Act in the General Assembly. While he said the bill is straightforward enough to pass on its own, he acknowledged it may be difficult without being tied to a larger legislative package.

Cunningham, the bill’s Senate sponsor, said he was “not opposed” to attaching it to an omnibus bill, but said the funding cliff necessitates quicker action, “or we’re going to really fall behind when it comes to generating renewable energy in Illinois.”

“We’ve kind of gotten used to the practice as legislators of making big energy policy changes all at once. And unfortunately that’s one of the reasons why this legislation has been tied up,” he said.

There are various interests in play as the state tries to enter a carbon-free future while keeping energy costs low and ensuring the state has enough available energy producers to keep the lights on at peak usage hours, according to Sen. Michael Hastings, D-Frankfort. As chair of the Senate Energy and Public Utilities Committee, Hastings has been taking part in energy reform discussions for months.

He said it may be difficult to pass a bill in a “lame duck” session of the General Assembly before those recently elected in November are seated, due to the complexity of the various energy bills and an unclear leadership situation in the House.

The other major initiative before lawmakers, which is far more sweeping than the Path to 100 Act, is the Clean Energy Jobs Act. That bill deals with electrification of the state’s transportation sector and overhauls the way energy capacity is procured among other initiatives.

It’s backed by a number of labor unions that are part of the Climate Jobs Illinois coalition, the Illinois Environmental Council and a number of other advocates.

One of CEJA’s key measures would remove Illinois from the multi-state PJM capacity auction, putting the power to procure guarantees of future energy production in the hands of the state in order to give Illinois more authority to focus on renewables instead of carbon producers.

But Hastings said one difficulty that arises from such an approach is that the PJM market serves northern Illinois, essentially north of Interstate-80, while the rest of the state is on the MISO grid. He said working groups are currently exploring the possibility for a statewide solution on capacity procurements, rather than one that affects just the PJM market.

But there are also a number of coal-to-solar initiatives and other lower key energy measures to be considered, Hastings said.

“We have to have a diverse energy portfolio that’s clean, and that includes nuclear, wind and solar and then you also have to have some offset capability in the natural gas world,” he said. “You have to look at it globally.”

jnowicki@capitolnewsillinois.com

Madigan floats income tax increase; GOP leader asks for spending cuts

Harmon re-elected Senate president; contested race for House speaker