Comptroller report shows state’s finances in bad shape, but improving

By Peter Hancock Capitol News Illinois — September 4, 2019 SPRINGFIELD — The state of Illinois ran up a deficit of more than $7.7 billion in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2018. But as bad as that sounds, it was only about half as bad as the $14.6 billion deficit amassed the year before.

SPRINGFIELD — The state of Illinois ran up a deficit of more than $7.7 billion in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2018. But as bad as that sounds, it was only about half as bad as the $14.6 billion deficit amassed the year before.

That’s one of the conclusions from the latest Comprehensive Annual Financial Report that Comptroller Susana Mendoza released Thursday. It’s the first such report released since the end of the state’s historic two-year budget impasse during former Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner’s administration.

The 397-page report offers an intensely detailed look at the state’s overall financial condition as well as an analysis of economic factors that could affect state finances into the future.

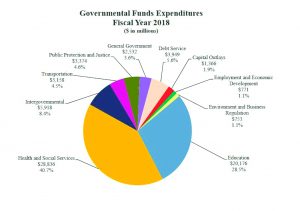

It notes, for example, that spending on health and social services accounted for the largest single area of state spending during the year, totaling nearly $28.9 billion, or almost 41 percent of the state’s budget. That was followed by education, including K-12 and higher education, which accounted for $20.2 billion, or 28.5 percent of state spending.

According to the report, the state’s overall financial condition improved during that fiscal year, which began July 1, 2017, largely because the final budget plan that passed in late August of that year included significant increases in both individual and corporate income tax rates coupled with authority to issue bonds backed by future tax receipts that were pledged to pay down debts that were incurred in prior years.

The 2017-2018 budget plan also gave the state authority to transfer money out of various funds into the general fund, and to borrow from other funds, in order to defray operating costs. It also provided options for certain state employees to accept voluntary buyouts of their pension benefits — cash now in exchange for future pension payments.

Even with those measures, the report noted that the state’s overall “net position” — essentially the difference between all of its tangible assets and all of its liabilities, a statistic used to measure the overall financial health of a business or government — was a negative $136 billion.

Still that was also better than the negative $184 billion net position reported at the end of the 2017 fiscal year, an indicator that the state’s overall financial health improved during the year.

Looking forward, the report noted the state faces a number of “continuing underlying financial weaknesses” that will affect the state’s ability to meet its financial obligations in the future.

Chief among those, according to the report, is the state’s ability to manage its cash flow. Almost consistently since November 2000, during Republican Gov. George Ryan’s administration, Illinois has been running a deficit — bills on hand exceeding available cash — in its general revenue fund.

That’s largely the result of something that has become a common practice in Illinois over the past 20 years, known as “deferred liabilities,” which allows the state to incur obligations in one year and to pay them off with revenue from the following year.

Illinois ended the 2018 fiscal year with just over $2.2 billion in deferred liabilities, a decrease of nearly $3.9 billion from the previous year.

Illinois also faced an estimated $133.6 billion in long-term unfunded pension liabilities at the end of the 2018 fiscal year, plus another $55 billion in “other postemployment obligations,” including health, dental, vision and life insurance for retired state and university employees.

Finally, the state faces a large amount of long-term debt. Illinois ended the year with roughly $30 billion in general obligation debt — or debt backed by the full faith and credit of the state — plus another $2.3 billion in “special” obligation debt, which is backed by revenues specifically pledged to pay off that debt.

Interest and principal payments on that debt totaled nearly $3.8 billion during the fiscal year.

Although improvement was dramatic in fiscal year 2018, the state is far from recovery of the damage during the two-year budget impasse, and systematic budgetary issues still impede further significant reductions in the state’s unpaid bills, the report stated.

phancock@capitolnewsillinois.com

Critical data, and time, lost in compiling state financial report

By Rebecca Anzel

Capitol News Illinois

SPRINGFIELD — A major tech failure at two of Illinois’ largest agencies and a lack of a uniform financial system contributed to officials publishing a key document detailing the state’s fiscal health eight months late.

The Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, released Aug. 29, is used by ratings agencies to determine Illinois’ credit rating, which affects the interest rates it receives for bonded projects.

Auditor General Frank Mautino and Comptroller Susana Mendoza, whose offices contribute to the document, agreed a primary reason Illinois’ report was the last one completed in the country was due to the loss of one quarter of the state’s Medicaid data.

The Department of Human Services and the Department of Healthcare and Family Services both use a system that determines residents’ eligibility for public assistance, for which the state receives federal reimbursements. When a third-party technology vendor was completing an update to that system, 25 percent of Illinois’ Medicaid program data was deleted, Mautino said.

Agency officials asked for an extension to work with the federal government to verify the accuracy of information lost in that erasure. Before the CAFR can be completed, auditors verify the books of each agency, sending that data then to the comptroller’s office.

“This is the thing that’s different this year that I don’t know of has happened anywhere at any other time,” Mauntio said. “It’s a big factor.”

The mistake was additionally impactful because of the two agencies it affected. Combined, Mautino said, they make up 28 percent of the revenue and 31 percent of the expenditures of all governmental funds in Illinois.

“That is a big number, and when you have a problem with that number, it impacts the financial statements of the state,” he said.

Mendoza criticized former Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner’s administration for its use of third-party contractors.

“We should not expect outside consultants to perform critical government functions, especially regarding data involving eligibility determinations under the state’s Medicaid program serving the state’s most vulnerable citizens, without adequate controls to protect the state’s program and ultimately state taxpayers,” she said in a press release.

The auditor general and Mendoza did not agree the state’s lack of a uniform financial system contributed chiefly to the report’s delayed publication.

Mautino said Illinois officials do not have “great financial controls” because each agency has its own financial reporting system that “can’t speak to each other.” When auditors compile information for the CAFR, they must convert the data first. That takes more time and leaves open the possibility for human error.

“Accurate and timely financial reporting problems continue to exist even though auditors have: continuously reported numerous findings on the internal controls, … commented on the inadequacy of the financial reporting process of the state, and regularly proposed adjustments to the financial statements year after year,” states an opinion of the CAFR published by the auditor general’s office Thursday.

Mendoza noted in a news release she “agrees” Illinois needs a uniform financial system, but pushed back against the idea it was a “primary” reason for the report’s late release.

ranzel@capitolnewsillinois.com