140-year-old Chicago club supports female classical musicians

By Jean Lotus Staff Reporter — April 14, 2016

Pianist Natasha Stojanovska performs at a “salon” concert for members of the Chicago Musicians Club of Women.

Chicago’s Musician’s Club of Women was formed in 1875, three years after the Great Chicago Fire, and still exists to this day.

The group hosts two monthly free classical concerts and gives away tens-of-thousands of dollars in scholarship money yearly to Chicago-area female classical musicians. They call themselves the “oldest musical club in the U.S.”

“We’ve lasted 142 years because we’re not all about entertainment,” said Lee Karton, of Chicago, the club’s president. “We are different because we provide venues for our musicians, we support our musicians and we host quite a few of the top women musicians in this city.”

Club members include Chicago Violinist Rachel Barton Pine, Lyric Opera Soprano Nichole Cabell and Russian Pianist Yana Reznik. Lyric Opera Bass Samuel Ramey is an honorary (male) member.

“Active” club members, who are professionals, perform monthly in a members-only concert/lunch at Union League Club and sometimes at private residences. These gatherings include “Associate” members who are fans, but not working musicians.

But when the club began, it wasn’t so easy for women musicians to get the chance to play.

The club started with a handful of Victorian-era female pianists and singers who wanted to perform, but had few opportunities.

“Four ladies, fine pianists used to meet in the ware-room of a piano firm for practice,” wrote Chicago historian John Moses in 1895.

They called themselves the Amateur Musical Club, part of a fad of “amateur” arts and philanthropy clubs started by women around the country. The musicians had the ambitions and the talent, but the chance to perform in a man’s world was missing.

“Performing professionally was not fully open to them in the same way it was open to men,” said Rima Lunin Schultz, a women’s history professor at University of Illinois at Chicago and author of “Women Building Chicago 1790-1990: A biographical dictionary.”

“At that time, and even into the 20th Century, professional women found it necessary to create female organizations to give themselves support and create a network of collaboration, training and scholarships,” Lunin Schultz said.

The foundresses of the club are obscured to history, their identities are entombed in their husbands names — as was the fashion: Mrs. John Clarke, Mrs. Frank Gorton, Mrs. Charles Haynes, Mrs. George Carpenter and Mrs. William Warren.

But one name rings a bell: Mrs. Theodore Thomas.

Theodore Thomas was the German conducting prodigy who traveled the world performing at the top venues in Europe. He was lured from New York by Chicago businessman and booster Charles Norman Fay who offered Thomas his own orchestra, and promised to build a grand hall (Symphony Center) to house it.

“I would go to hell for my own orchestra,” Thomas famously said.

Rose Fay, Charles’ sister, soon met and married Thomas. Her sister, Amy Fay, was a professional pianist.

In the early years of the Amateur Club, membership was limited to musicians only, by audition, said Karton. Membership boomed when the club welcomed unskilled, but enthusiastic music fans. Scholarships to help women pursue their musical training began as early as the 1890’s, Karton said.

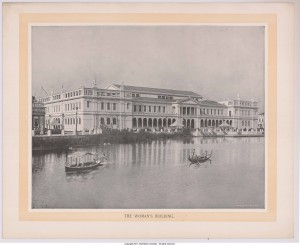

The “Woman’s Building” at the 1893 Columbian Exhibition and World’s Fair was an inspiration. So was Illinois native Maud Powell, the first American violinist of either gender who cracked the top echelons of international solo performance. Powell was a member.

The “Woman’s Building” at the 1893 Columbian Exhibition and World’s Fair was an inspiration. (Photo courtesy of Ball State University)

In December, 1904, Theodore Thomas conducted the first performances of the new Chicago Orchestra at the brand new Symphony Center. But he caught influenza and died a few weeks later.

Rose became a traveling advocate for the club, exporting the idea to start new Amateur Clubs around the country.

In the new symphony building, the group first hosted concerts by world-famous stars to “cultivate a taste for good music” in Chicago, Karton said. But pretty soon, since their active members were professional musicians, the club focused on supporting performance opportunities for their own membership. They had created the cultural atmosphere in Chicago and built support for the venues.

In 1916, club members decided they weren’t fooling anyone, and “amateur” was dropped. Club members officially changed their name to the “Musicians Club of Women.”

One hundred years later, the club hosts a monthly free daytime first-Friday concert between September and June at the Buchanan Chapel at Fourth Church on North Michigan Ave.

They also present a fourth-Monday scholarship-winner recital at 12:15 p.m. at Preston Bradley Hall in the Chicago Cultural Center.

Scholarship contestants must be recommended by a music teacher or professor.

This year, the distributed $60,000 in scholarships to several classical singers and other musicians including a basoonist, pianists, string players and a flutist.

“We had three 16-year-old winners this year,” Karton said.

Membership Chair Diane Moses said the club keeps going because, “a lot of people are fully passionate about the wonderful music.

“Some of our members have gone on to international careers as a result of our scholarships.”

— 140-year-old Chicago club supports female classical musicians —