A great photographer’s stubborn insistence on his work’s value

By Irv Leavitt for Chronicle Media — May 14, 2018

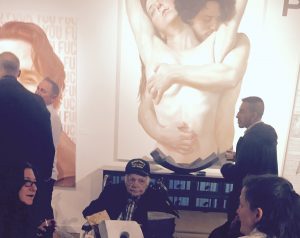

The late photographer Art Shay, in cap, at Gallery Victor Armendariz, Chicago, May 5, 2017. (Photo Irv Leavitt / for Chronicle Media)

“That’s too bad,” a former newspaper editor said when I told her that Art Shay, one of the best American photographers of two generations, had died. But by her tone of voice, it didn’t sound like she would miss him.

“He was annoying,” she explained. “He was always telling me I didn’t know what I was doing.”

Shay, indeed, had no compunction about telling media bosses that they were, well, inept. Nobody likes being called inept. It’s particularly galling when it comes from someone like Shay, who was rather spectacularly ept.

But maybe if all those newspaper geniuses of yesteryear had listened better, and handled their businesses the way Shay did his, you wouldn’t see condominiums where their headquarters buildings used to be.

Shay took pictures of Elizabeth Taylor, James Baldwin, Muhammad Ali, Marlon Brando and his old pal Nelson Algren that burned themselves into your memory. He took equally stunning pictures of people with more forgettable names, doing memorable things. And he did some pretty writing in between the pictures.

He died at the end of April in Deerfield, where he had lived much of his adult life. At 96, he was, as the saying goes, old enough to know better. And he did.

Shay was usually where he needed to be when he needed to be there, and stopping him from doing what he went there for was as easy as separating a German shepherd from a lamb chop.

I know a lot of great photographers whose reputations took off after a great shot, maybe at a street protest or a high school football game. Shay took his career-making photograph while in the World War II U.S. Army Air Corps. He caught the collision of two bombers over his own airbase.

A navigator, he always took a camera with him on bombing runs. One time, the camera was shot right off his chest. He liked to tell that story.

Here’s another, even older story he told me in 2011.

In the first year of the war, he was a teenage busboy in the Catskills.

“I got fired because I was serving breakfast to Harry James and Betty Grable, and spilled a whole plate of scrambled eggs on his knees.

“He was wearing shorts. He jumped up. Betty Grable jumped up.

“Mrs. Novack (Bella of the then-famous Novack resort family) said, “I hope de var ends very soon, because den I vill be able to get good busboys.”

Here’s how he saved his job.

He had taken a pre-breakfast photo of movie star Grable and her bandleader boyfriend James, who was wearing a Laurels T-shirt. That picture had great promotional possibilities for the Novacks. Problem was, James had the shirt on inside-out.

Shay took the film to the busboys’ quarters, where he had built a tiny darkroom in his 5-by-7 room. “By some miracle,” he said, he managed to reverse the writing, partly by cutting up the negative and flipping it over.

“She hired me back again,” he said.

She paid him for the photo, too.

“I don’t let anybody use my stuff for free,” he had told me years before. He didn’t really say “stuff.”

He wasn’t kidding. He once refused to give me a photo he had taken that I wanted to use with a story. The story was promoting the publication of one of Art’s own photography collections.

“Let ’em buy the book,” he said.

He told me that any time one of his shots was used without permission, he threatened a lawsuit. And if he didn’t get paid, he followed through.

His philosophy was almost completely disdained at the dawn of the Internet era: the concept that journalistic product, like any other product, has value. If you give it away, you set a new value. That value is about as high as a ladybug’s butt.

All the media big shots I knew were advised, early on, to build a website that charged money to see the product. And if somebody used something without permission, they should slap them around in court.

I watched from a newsroom as they decided to do the opposite. I gave up arguing, and just did my job for as long as it might last. Not my circus, not my monkeys, as another old saying goes.

The newspaper ringmasters feared that if they charged admission to their digital Big Top, the competing carnivals would undercut them by letting the rubes in for free. So everybody got to see the elephants and the bearded lady just for the push of a button.

Newspaper companies, of course, were often serving some demanding masters: shareholders. They still wanted 20 percent annual return on investment, like the old days.

Somebody needed to tell them, “No. Can’t do it, at least not now. I’ve got to build a firewall, and spend some of our profits to put incredibly cool stuff behind it to make it worth the money to readers.”

A media leader going into a shareholders’ meeting could have used the kind of insane courage Shay had. Through 52 bombing missions, he said he never once worried that he wouldn’t be coming back.

Most of the old media big shots wouldn’t even take the risk that they’d miss a car payment.

One of the results of their bravery shortage was that they put themselves on an equal footing with Internet-only startups that don’t pay big money for printing and delivery and everything that goes with that. Those outfits have much less to worry about losing if they get caught telling less than the whole truth.

So there’s a lot of lying out there.

Recently, most newspapers have finally decided to start charging for their digital product. It doesn’t take as much guts, now that everybody’s doing it.

So they throw up a screen blocking their content, begging for money, every time you make the mistake of finding something that you just might want to read.

“You have three free stories left. Stop this annoying nonsense by subscribing.”

But it doesn’t stop. Every time you want to read something, you’re likely to get another screen demanding that you pay up. In the corner, it says, “Already a subscriber? Then go look up your user name and password and just try to get this thing off your phone.”

And then you find out that you didn’t want to read the darn thing anyway.

You’re reading this darn thing online or in a publication of Chronicle Media, which has only been around for a few years. Unlike most news startups, the company has invested in print products to go along with the digital.

Interestingly, they don’t play games with you about paying for their online stuff. Everything is free. And after many of the stories, they have a sentence like this:

Free subscription to the digital edition of the Cook County Chronicle

You can click that and get all the stories in your email without even having to look for them. Still free, still no screens blocking and begging.

Ironically, now that most printed papers are charging for their digital versions, I think what Chronicle Media is doing — guilelessly giving away the Internet product — takes a lot of guts.

It may also be stupid. But it’s certainly gutsy.

I never asked Shay. But I think he would think so, too.

— A great photographer’s stubborn insistence on his work’s value —-