Fifty years later Royko’s ‘Boss’ still offers us important lessons

By Bill Dwyer For Chronicle Media — March 28, 2021 Half a century on, it’s easy to forget Chicago’s darker realities back in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Half a century on, it’s easy to forget Chicago’s darker realities back in the 1950s and ‘60s.

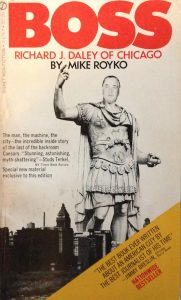

It’s also easy to forget the impact legendary Chicago news columnist Mike Royko’s new book, “Boss,” made on Chicago and the nation.

“Boss,” the landmark study of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, celebrates its 50th anniversary Thursday. While the hardcover edition was published Jan. 1, 1971, the paperback version, which sold in the millions and was read by countless everyday working class people around the Chicago area, was published April 1.

A re-reading shows just how much Chicago has changed. It also shows how much Chicago and America have not changed in key ways.

Royko’s book pulled back the curtain on a man who for more than 20 years was widely considered the second most powerful Democrat in the country. But Royko’s opus was about more than one man. It was a portrait of both a great American city’s public face and it’s dark and sordid underbelly.

Royko’s contemporary Studs Terkel wrote that Boss was “a stunning portrait” that “probes not only into the psyche of a neighborhood bully, but into the nature of the city that has so honored him.”

It didn’t go well with some people. Daley’s wife, Eleanor, reportedly went around her Bridgeport supermarket turning around all the copies of “Boss” on the racks, and threatened to stop shopping there if they didn’t remove them from the store.

Royko got a huge kick out of the whole kerfuffle, even thanking Mrs. Daley in his Daily News column for drawing attention to his book. “She put a couple of dollars in my pocket,” he wrote, adding he might send her a leatherbound, gold embossed edition of “Boss” for Christmas.

But the ugly truth is that a majority of white, ethnic Chicago did honor Daley, in large part because he reflected their aspirations and their fears. In simple, direct prose and artful phrasing mixed with telling anecdotes, Royko laid out how Daley viscerally understood the tribal values in the city’s white ethnic neighborhoods, clannish enclaves that remained distrustful of “outsiders” two and three generations after their forebear’s arrival.

Daley’s Chicago was a city that on its surface sparkled and soared skyward, blessed with many hundreds of millions of dollars lavished on the downtown area and lakefront and an ever expanding expressway system in the ’50s and ’60s that cost hundreds of millions more in federal dollars.

But it was a grandeur built on the long neglect of many, mostly minority neighborhoods, and on outright violations of people’s basic civil rights, in particular Black folk’s rights.

Beneath the concrete and steel monuments to Daley’s grand vision, many hundreds of thousands of average and poor citizens, most Black and brown, suffered from both systemic government neglect and routine abuse at the hands of a corrupt and racist police department.

It was predictable. Royko wrote about Daley’s beginnings in a violent and racist Bridgeport “social club” to his evolvement into a clawing and cunning up and comer in the Democratic Party ranks, to his eventual ascension to the fifth floor mayoral suite and his first 16 years as mayor.

Royko’s unsentimental prose is imbued with his deep disdain for Daley’s disregard for other’s rights, and for the corrupt political party apparatus he controlled. In similarly unsentimental terms, the book conveys Royko’s deep love and respect for Chicago’s people, its streets and neighborhoods, the bars and countless haunts where real people without power lived and worked, played and died.

Half a century later, Chicago and America are still struggling with those same fearful and hateful tribal instincts and deep-seated racism, a reality laid bare by the ascendance of Donald Trump and his domination of a right-wing cultural movement that has survived his removal from office.

Rokyo’s perceptiveness to the twists and kinks of human biases would be a welcome addition to today’s dialogue on America’s post-Trump culture. He would have immediately recognized the animating spirit in Donald Trump that attracted millions of threatened, fearful people. Nearly half a century after Boss Daley died, millions of Americans still love a bully, just so long as it’s their bully, a bully who reflects their values, who makes them feel comfortable embracing their darker angels and baser impulses.

Like Daley, Trump is at heart a bully, one hell bent on acquiring power through whatever means available. Like Daley, Trump’s success stemmed from his ability to harness white ethnic tribalism. And like Daley, Trump is vindictive.

But Donald Trump is no Richard J. Daley. Trump sees power mostly as a path to greater and greater riches. Daley saw power as an end in itself, power he relished using to tear down and rebuild the city in his vision.

Trump tore down the structures of federal governance in an attempt to solidify his power. Royko showed how a young Daley set about learning how the mundane, but essential gears of governance worked at each level. He then diligently set about repurposing them to his own needs, using each and every lever of governmental power with an astounding degree of control and effectiveness that Trump could barely imagine, and never had the discipline to master.

Daley was as vindictive as Trump, but Daley, who had a long memory that wasn’t put to rest until each and every score was settled, won just about every fight anyone ever picked with him. Trump blustered and tweeted and, at worst, intimidated people into silence.

Royko’s lasting genius was his ability to show how an old-school big city mayor tapped into ethnic fear and jealousy to attain and maintain power.

Fifty years later, all across America, the fear is still here, jealousy has given way to white grievance, and millions of people in America still want a political boss who gives them permission to be comfortable with acting out their hate.

Royko, sadly, is long gone.

Bill Dwyer is a semi-retired journalist who covered the near west suburbs for Wednesday Journal, Inc. and the Sun-Times News Group. He won the Society of Professional Journalists Peter Lisagor award for exemplary journalism in 2005 for political commentary, and is a five-time Lisagor finalist, among numerous other awards.