Leavitt: Our happy lives among the cheats, thieves and grifters

By Irv Leavitt for Chronicle Media — January 15, 2020

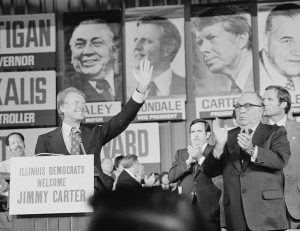

Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley at the 1976 Illinois State Democratic Convention in Chicago. Questions would be raised about all four of sons’ enjoyment of city business or jobs during their father’s tenure. (Photo by Thomas J. O’Halloran from the U.S. News & World Report collection at the Library of Congress)

Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley was caught shoveling $1 million worth of no-bid city insurance contracts to his son John in February 1973. He delivered a shameless and unintentionally comical defense to a room full of Democratic committeemen.

“If I can’t help my sons, then they can kiss my ass,” he said. “I make no apologies to anyone. There are many men in this room whose fathers helped them, and they went on to be fine public officials.

“If a man can’t put his arms around his sons, then what kind of world are we living in?”

For many Chicagoans, the most painful aspect of this incident was not that their mayor had publicly doubled-down on the merits of nepotism.

The hardest part to take was that the committeemen, the courts and most of Daley’s constituency readily swallowed the concept of a mayor steering government business to his son, even though it doubtlessly meant it cost taxpayers more than it should have. It was also apparently acceptable that honest providers had been shut out.

People actually made jokes about it, in print, broadcast, and over the water coolers.

Five years later, I was living in the South, where people would often ask me about my accent. “I’m from Chicago,” I’d answer, “where we all walk around with politicians’ hands in our pockets, and we think it’s funny.”

We still have a hard time taking it all seriously. After all, that hoary old crook Ed Burke was indicted on charges of shaking down a business a year ago, and was reelected alderman of Chicago’s 14th Ward a month later.

After the election, some of the hilarity finally died down. A new mayor is hacking away at the rules that gave Burke and other City Council comedians the clout to squeeze people who needed something from their government.

But around the country, people often retain a sense of humor about being shafted, by politicians and almost anybody else who can.

For instance, there seem to be more wisecracks than worries about recent news that the Houston Astros apparently cheated their way through the 2017 season and World Series. They used electronics to steal catchers’ signs, according to credible and confirmed reporting last fall by Ken Rosenthal and Evan Drellich of The Athletic.

The Astros’ principal methodology wasn’t exactly the height of subterfuge. They captured the signs via video, then banged on a garbage can to signal whether a fastball or breaking pitch was coming.

Knowing what’s coming makes hitting much easier. Players have said that Astros hitters, even when facing their best pitchers, were complete beasts.

At this writing, The Athletic has a new story attributed to three Red Sox players, maintaining that Boston’s march to the pennant in 2018 was aided by analyzing live video of catchers’ signs under the stands.

The Athletic reports that before that season, baseball’s commissioner warned all the teams in writing not to do such things, but the Red Sox apparently didn’t expect serious consequences, if caught.

MLB monitored team video rooms in the playoffs, but not the regular season. Not even for the Red Sox, who, like the Yankees, had been fined for some electronic sign-stealing the previous season.

Most baseball fans seem to have greeted this news with light-hearted complacency, even though we may have had two World Series championship teams in a row that shouldn’t have even been in the playoffs.

Cheating pays. Since the Astros started being competitive four years ago, the value of the franchise has more than doubled to $1.8 billion.

The day before The Athletic’s Red Sox scoop, you may have read about another questionable activity by the rich and famous.

Former Texas Gov. Rick Perry did something amazing just for its brazenness.

Two years ago, Donald Trump had plucked him from the board of a Dallas-based oil and gas pipeline company named Energy Transfer to be U.S. Energy Secretary, despite the fact that Perry had said that the cabinet position shouldn’t exist.

Perry took office Jan. 19, 2017. It was the day after the Army Corps of Engineers began a two-year impact study of an environmentally sensitive route segment of Energy Transfer’s much-maligned Dakota Access Pipeline.

Jan. 24, Trump told the Army Corps to back off. Perry’s new boss effectively gave his old boss the go-ahead to build the pipeline.

Later, Perry’s name came up a lot in the Ukraine scandal that got Trump impeached. On Oct. 6, Trump blamed Perry for advising him to make last summer’s now-infamous call to Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky. On Oct. 17, Perry officially told Trump he’d be out by year’s end.

He was gone Dec. 2. On Jan. 6, he accepted a paid position on the board of something called LE GP LLC, which is the general partner of — wait for it — Energy Transfer.

This news was greeted not as much by horror at the blatant conflicts but by jokes about them and Perry’s lack of intellect.

Yes, Perry has always seemed dumb, and his public life has been laughable. But right now, he seems dumb like a fox as he’s laughing all the way to the bank.

So who’s more stupid? Him, or us?

Every day, new betrayals of Americans are revealed, and we react, typically, with equanimity and good humor.

We’re usually not pouring into the streets in protest, or rushing the doors of big government and corporate America, demanding redress. Many of us never even vote.

Perhaps the reason is that we think that corruption is all about money, and everybody’s doing it. So what’s so bad about a little cheating, as long as they save a few morsels for me?

But it’s not just money. Perry’s activities will lead to environmental degradation. People will die because of some of the things he promoted, in and out of office. Some may already be gone.

Chicago aldermen who made bribes their most important considerations are likely to have fostered changes in neighborhoods that were the opposite of what those neighborhoods needed. They’ve been too busy lining their pockets to adequately address tough problems like affordable housing and mental health support for the poor.

You don’t have to be homeless or mentally ill for those failures to adversely affect your life. You don’t even have to live in Chicago.

The day after Perry officially went back into the pipeline business, Chicago’s WBEZ radio reported on a 2012 email it had dug up. It had been sent by super-connected former Illinois lobbyist Michael McClain to two big shots in Gov. Pat Quinn’s office. In the email, McClain — a pal of Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan — pleads to preserve the job of a state bureaucrat named Forrest Ashby because “He has kept his mouth shut on Jones’ ghost workers, the rape in Champaign and other items. He is loyal to the administration.”

The news has reportedly led to an investigation, and Ashby losing his state consultant’s contract.

But Ashby, McClain and the two big shots — Gary Hannig and Jerry Stermer — at this writing have apparently not felt compelled to explain what’s behind the letter.

Everybody else even tangentially involved, who has been less able to hide, has answered with some version of “What rape? What ghost payroll?”

And so far, they’ve all gotten away with it because, as earlier discussed, we don’t care a lot about such things. Political reporters are fascinated, but for us, it’s more of the same old stuff. Since Trump, things like this are even less likely to bother us.

We just want to live our lives. We play with our phones, watch sports on TV and shows on Netflix.

Ricky Gervais, stop telling us mean things about Hollywood. Ken and Evan and your buddies at The Athletic, give it a rest.

We’re not worried that sports is rife with corruption, from steroids to stadium scams to deflated footballs. We’ll just assume that every game is on the up-and-up.

Say it ain’t so, Jose Altuve.