Leavitt: The restaurant business has changed a lot, but we ain’t seen nothing yet

By Irv Leavitt for Chronicle Media — May 29, 2019

At the Chicago restaurant show, Suzumo International Corp. displayed a machine that made rice planks like a skilled sushi chef. (Photo by Irv Leavitt)

When my sister and I were kids, Dad often took us to the annual National Restaurant Association show in Chicago. A restaurant supply salesman, he usually had extra tickets, which was nice, because the show was like a giant free smorgasbord run by pretty ladies and other agreeable people.

After a 50-year absence, I went back to McCormick Place for this year’s extravaganza. There was still a lot of free food and nice salespeople, but it was not my father’s restaurant show.

It’s not my father’s restaurant business anymore, either.

Jerry Leavitt sold restaurant hard goods, compiled in a 25-pound product catalog he called The Book. It was a five-inch-thick bundle of oversize loose-leaf slick paper held together by a dozen or so steel rings, covered front, back and bottom by a thick expanse of leather that terminated in sturdy leather handles on top.

Catalogs. Paper. What a joke. I was the only person I saw at the giant convention hall writing anything down.

“Paper is something ridiculous,” said Richard Lopez, one of the new breed of restaurant techies. “Everybody has a smart phone, tablet, tools that feel natural to them and that they are able to use in seconds.”

Lopez wasn’t talking about selling. He was talking about keeping track of everything that goes on in a restaurant.

So were hundreds of other tech people at McCormick Place, all telling versions of the same tale: Just cook, plan menus, and be nice to people, and we’ll do almost everything else for you.

Tony Ventre, a vice president at Beyond, a New Jersey company that handles everything from payroll to inventory management to supply reordering, said there are three kinds of independent restaurant owners now: About 70% of them are “craftsmen,” men and women fascinated by the lore of food; about 25% are “freedom fighters,” people who fled some other business to open a restaurant, and about 5% are “mountain climbers,” those aiming at growing a big chain. He said the first two groups, at least, should definitely consider avoiding slogging through all the details, and leave that up to something like Beyond.

If you’ve been in the restaurant business or a similar trade, this may all sound familiar. It’s the pitch your brother-in-law the underemployed accountant gave you, only with better technology, and actual experience.

Ventre seems like a nice guy, and his company seems to have its heart in the right place: it has funded 1,500 scholarships with a foundation partner, to lift up foster kids, he said. And it has a commitment to transparency and other good business practices.

But is paying considerably extra for tech-based outside-the-walls restaurant management the savior of an industry known for failures before the age of two? Or just another way to fail?

I’m rooting for it to succeed. Dad’s boss took back his catalog after 35 years because of too many customers he considered friends who went from “net in 30 days” to “net in 120 days” to “we better throw a net over that guy before he files for bankruptcy.” And the failure segment of the restaurant business is still a growth industry.

Shrinkage is a real threat to keeping a restaurant afloat, a California man named Jeff Clifford told me. He’s an account executive at BirchStreet Systems, which is in the procure-to-pay business. They handle everything from purchase to payment, complete with analytics.

The analytics they were demonstrating at McCormick Place involved shooting bottles of booze with a ray gun to see how much was still in there, after the bartender gave freebies to her pals.

Clifford said you can adjust the standard from 95% of honesty to 66%, depending on how nice you want the server to be to the regulars.

I saw new tech applied to hardware, too. SwiftSensors will build you a system that will call you on the phone when your freezer or walk-in gets too hot. You don’t even have to stroll over and look at the thermometer anymore.

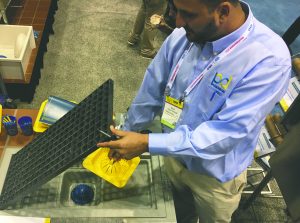

An outfit called Permadrain will use a 3D printer to make a custom dome-shaped strainer for your kitchen sink, which is then bolted on. Then it’ll make a basket to fit over that, that the dishwasher can take off and dump. No more forks down the drain. “Dummy-proof,” Permadrain’s Philip Ziegler calls it.

Lopez, the fellow who gave the funeral to paper early on in this screed, works for a Connecticut company called Transact that makes the little paper labels that go on prepped food containers to signal operators when it’s expired. A customer wised them up a while back with a question, he said: “What else do you do?”

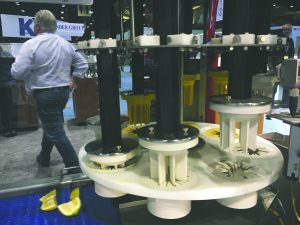

This $70,000 machine, on display at the Chicago restaurant show, can segment 90 fruits per minute. (Photo by Irv Leavitt)

In March, they answered with BOHA (Back of the House Automation), which appears to leave nothing to chance in the part of a restaurant you don’t see.

On the planning end, vendors’ item availability is communicated to the restaurants in advance. On the workaday end, some supervisors don’t have to come in early, Lopez said, because staff gets its orders on phones or at Internet stations, and have already chopped the celery and poached the tomatoes before the boss gets in.

Every food task comes back to labels. If a staffer comes down with a contagious disease, everything he made can be found and 86’d.

When the prep cook starts a task, he checks in. When he finishes, another check. When he cleans the bathroom, he checks every subtask — washing the toilet, replacing the towel — to make sure the main task actually gets done.

When it doesn’t, Lopez said, it’s easier to find out why. He related the tale of a kitchen staff seemingly shirking cleaning the French fryers, but the employees maintained there wasn’t enough time. The system turned over the information that the fryers actually took twice as long to clean as expected. So for two hours per day, twice a week, shifts were made to overlap so the job could get done.

All this tech gives the chef and the boss time to make a restaurant appealing, Lopez said.

So does another new technology, ordering kiosks that are, so far, mainly at a few fast-food establishments and sports venues. The people involved in that say that it means the hemming and hawing over the menu is transferred away from an employee’s responsibility to that of a machine, which doesn’t get paid by the hour.

The concept, as envisioned by McDonald’s, seems to be to move more people to the back of the store to prepare a bigger menu. McDonald’s has for decades been mired in a vicious cycle of innovating new food choices, only to suspend them because there wasn’t enough time to make the new things.

Many of the technology mavens I met at the restaurant show used the word “productivity,” and the ones who didn’t usually mentioned how many minutes or seconds a particular task should take. I understand that everything is pointed at getting dinner to a customer before it gets cold, but I can’t help wondering if the brave new world of restaurants is going to soon be, like a lot of other industries, only fun for those who own them.

It’s certainly going to be different for the customers. I saw demonstrations of facial recognition systems that could be connected to electronic message boards that can show patrons the particular kind of food that their demographic might indicate.

Eventually, I’m told, a sensor will pick up your phone as you drive into McDonald’s, and when you get in the drive-through line, show a picture of what you usually order, with a picture of the sides you never ask for.

Which, I’m sure, will be trumpeted as a great step forward for employees: Forever more, no one will have to ask, “Do you want fries with that?”