State board of health investigates Lyons D103 for asbestos violation

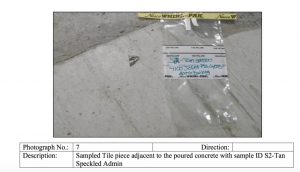

By Jean Lotus Staff Reporter — March 27, 2017A dime-sized chip of speckled tan floor tile was the clue that led investigators from the Illinois State Board of Health to launch an investigation into Lyons Elementary School District 103 for asbestos abatement violations March 1.

The ISBH Department of Environmental Control is “investigating this situation and is providing compliance assistance to the school district,” confirmed Melaney Arnold, the board’s communications manager.

An inspector for the Cook County Department of Environmental Control found the tile chip Feb. 15 on the floor in Room 119 at the district’s administrative offices, 4100 Joliet Ave., where renovations have been taking place since February.

According to dispatch records obtained from the Village of Lyons, the school fire alarm was activated at 10:17 p.m. Feb. 9. The incident occurred about an hour after a school board meeting had ended.

Witnesses told investigators the district director of maintenance used a dry-saw to cut an 8-foot trench in the tile floor to accommodate computer cables and lines for the IT department. Dust from the cut tile activated the fire alarms, school personnel said. Lyons Fire Chief Gordon Nord did not return calls about the incident.

“That tile’s got asbestos in it and there was stuff all over there, dust everywhere,” said a school employee who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution.

The employee worried that dust also may have been sucked into the building’s ventilation system.

The next morning, former school board member Deanna Huxhold visited the district offices and noticed a layer of dust on floors and surfaces.

“There was so much dust on my shoes when I left, it made a trail of footsteps out the door,” Huxhold said. She is now worried she may have been exposed to particulate asbestos fibers.

According to reports obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, the County received a tip about a possible asbestos violation at the school district. An investigator arrived at the district on Feb. 15.

Maintenance Director Ryan Grace first showed the inspector the gymnasium floor in George Washington Middle School that was being replaced after rain damage, the report said. Grace was unclear where any asbestos abatement paperwork was kept, the report said.

In the administration offices, the inspector observed an 8-foot long concrete-filled trench six-inches wide on the East side of the room. The trench was cut into the tan 9-by-9-inch floor tiles.

“The concrete did not appear to be new and was completely solid to the touch,” the report said.

Grace told the inspector he did not know when the concrete was poured.

“Grace stated a cabinet was previously stored on top of [the trench],” the report said.

But the little chip on the floor that matched the other tile suggested otherwise. The inspector photographed and bagged the chip and sent it for analysis. The County lab found the tile contained up to 5 percent dangerous Chrysotile asbestos fibers.

County inspectors called in the state environmental control engineer after they decided the trench had been cut recently, based on witness accounts and a time-stamped photograph Feb. 10 showing the trench only half-full of concrete.

County emails to the state environmental engineer suggested that the inspectors believed they were not told the truth.

A chip of floor tile tipped a county investigator to the possibility that a trench had been recently cut in asbestos-containing floor tiles at the Lyons School District 103 administration building. (Photo courtesy of Cook County Department of Environmental Control)

“It’s safe to say Ryan Grase [sic] lied to [the inspector] during her investigation from a file cabinet being over the exposed area in the admin building to make false statements with regard to when the concrete was poured in the trench,” a county administrator wrote. Grace declined to respond to messages and emails left for comment.

Fines from the state health department for improper asbestos abatement can run into the thousands of dollars and include fines for releasing particulates, fines per person exposed to the particles and fines for fraudulently reporting or not reporting abatement.

“We were always told, don’t do anything with the floor in the administration building because that tile is asbestos,” said D103 board member JoAnne Schaeffer. Asbestos abatement in schools is very expensive and must be completed by trained professionals, Schaeffer said.

“I feel concerned for [Grace] because he might have exposed himself to risk for mesothelioma,” she said. “And maybe the firefighters too.” Lyons firefighters are part-time staff with reduced benefits. Schaeffer said she did not know whether any administration staff or custodians had any medical follow-up.

Asbestos is present in almost all buildings built before the 1970s.

“Asbestos does not pose a problem unless it is disturbed — for instance if it is cut, razed, removed or damaged,” said Becky Schlikerman, Cook County spokeswoman in an email. “Asbestos floor tile is common in schools, but it is not necessary to remove the tile unless it has become damaged and/or friable. The Illinois Department of Public Health has very stringent rules and regulations when it comes to documenting the presence, removal, containment and location of asbestos in the schools and requires schools to keep an updated management plan on how to deal with asbestos,” she said.

In the past 10 years, the county issued 1,045 permits to schools for asbestos abatement, Schlikerman said. Permits cost $200.

Former maintenance director Thomas Sheehy worked with the County and a special asbestos abatement company when a school replaced the middle school roof in 2012, he said. Even a small patch of leftover asbestos containing material (ACM), had to be specially reported to the county for a variance, he said.

“This type of intergovernmental cooperation can only be accomplished if their [sic] is mutual trust and respect for the roles each agency plays in ensuring the health and safety of the project workers as well as the end users, i.e. students, faculty, staff and visitors to the school,” Sheehy wrote in an email. “Your word is your bond. The people you deal with in requesting this type of cooperation must trust that you will comply with all governmental requirements for both the actual work as well as reporting and documentation of same.”

Sheehy left the district in 2015, replaced by Grace, a childhood friend of Village of Lyons Mayor Christopher Getty.

Asbestos removal has caused big headaches for school districts in the past. In 2001, CUSD 230 in Orland Park incurred $100,000 extra costs in asbestos remediation imposed by the state board of health. The district had opted to have contractors remove asbestos tiles with a less-expensive heat-gun method, according to media accounts. ISBH stopped the work and made the district close two high schools for a month while abatement was completed.

Lyons Supt. Carol Baker serves on the CUSD230 school board, and Asst. Supt. Kyle Hastings has been the village president of neighboring Orland Hills for more than 20 years. Neither administrator returned calls, texts or emails for comment.

Schaeffer said she hoped the board would be briefed on the incident soon, and whether or not Grace was ordered to cut the tile by Baker or Hastings.

“I’m concerned that there may be lawsuits [for exposure to asbestos],” said Schaeffer. School district lawyers at Odelson & Sterk declined to return calls or emails for comment.

Free subscription to the Cook County Chronicle digital edition

Read the current issue of the Cook County Chronicle

— State board of health investigates Lyons D103 for asbestos violation —