Death certificates found of men killed in East St. Louis riots

By Beth Hundsdorfer Capitol News Illinois — June 17, 2022

A field of graves is pictured at Sunset Gardens of Memory Cemetery in Millstadt, the site where the remains of five unidentified Black men who were killed in a 1917 East St. Louis race riot were relocated. (Capitol News Illinois photo by Beth Hundsdorfer)

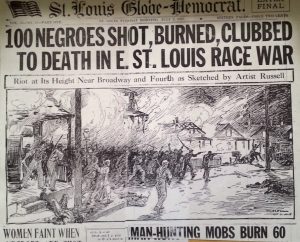

It was a tale told by older generations to the younger generations, of men shot and killed and their bodies tossed into a creek during one of the fiercest race riots in the country.

That tale was carried across the Mississippi River by those trying to escape the violence and through the generations of African American families who lived in East St. Louis in 1917.

Reginald Petty, the founder of the East St. Louis Historical Society, said he heard it. His elders told the children that 20 or 30 men were shot and thrown in Cahokia Creek.

“Everyone I talked to had a story, but this is the first time I have heard proof,” Petty said.

Capitol News Illinois discovered the death certificates in the Illinois State Archives earlier this year. The St. Clair County coroner’s records from the time period contained death certificates of five Black men, each identified only as “John Doe,” who were found in Cahokia Creek during and in the days after the massive riot.

Four were shot. One suffered a fractured skull.

“My grandparents would tell me about 30 or 40 men killed and thrown in the creek during the riots,” Petty said. “This is proof that this happened. That’s amazing.”

The five unidentified men were buried on July 3, 1917, in St. Clair Cemetery – the day after they were discovered in Cahokia Creek.

Decades later, they were disinterred and moved about seven miles to Sunset Gardens of Memory Cemetery in Millstadt to make way for the construction of Interstate 64. The records for the St. Clair Cemetery didn’t make the move with them.

Checks with the St. Clair County clerk and the Illinois comptroller’s office, who regulates cemeteries, failed to turn up any records for the formerly county-run St. Clair Cemetery.

Without those records, if they ever existed, there is no way to know the location of the John Does in their new gravesite in Sunset Gardens, further deepening the mystery of who these five men were who died at the hands of a riotous mob.

Petty said he considers them stitches in the fabric of East St. Louis history.

“They have become part of the East St. Louis community. All of our fathers, grandfathers, uncles. That’s how I will think of them,” Petty said.

The violence began May 28, 1917, after a city council meeting during which angry white workers formally complained about black migrants who came from the south to East St. Louis to work in the meat packing plants. Black families were attacked.

The death certificates detail the violence that began May 28, 1917, after a city council meeting during which angry white workers formally complained about black migrants who came from the south to East St. Louis to work in the meat packing plants and factories that were gearing up for World War I. Mobs began attacking Black residents, pulling them off streetcars.

Illinois Gov. Frank Lowden activated the National Guard, but troops were dispersed weeks later.

Tensions boiled over on July 1. A car occupied by white men drove through the Black area of the city and passengers fired into a group on the street, according to news reports of the time. Later, another car containing police officers drove through the same area and residents, assuming it was the first car, opened fire, killing two police officers.

This led to days of violence, including the burning of homes occupied by Black people, as well as assaults and murders.

The death certificates state the men died “by being thrown into Cahokia Creek during mob violence by parties unknown to us after being shot.”

In response to the violence, families built rafts to cross the Mississippi River or walked for miles to reach St. Louis.

Josephine Baker, a renowned actress, singer and dancer from St. Louis, once described the scene in a speech as she saw it as an 11-year-old.

“I can still see myself standing on the west bank of the Mississippi looking over into East St. Louis and watching the glow of the burning Negro homes lighting the sky. We children stood huddled together in bewilderment, frightened to death with the screams of Negro families running across this bridge with nothing but what they had on their backs as their worldly belongings,” Baker said in a 1952 speech.

And as those residents fled, they told their stories of violence, Petty said, and drew the attention of St. Louis newspaper reporters who wrote stories that circulated around the country.

Lowden reactivated the National Guard, which eventually quelled the violence on July 3, 1917 – the same day the five John Does were buried in St. Clair Cemetery in East St. Louis.

More than 300 homes in East St. Louis were burned. Death estimates were officially placed around 33, but later estimates by scholars put the deaths at around 200. Petty thinks it may even be more.

In addition to the death certificates for the five unidentified men found in Cahokia Creek, there were at least 10 other death certificates found in the state archives. Three of those died from a fire in a building at 8th and Broadway.

bhundsdorfer@capitolnewsillinois.com