Mining subsidence risk in southwestern IL may be worst in nation

By Bob Pieper for Chronicle Media — December 13, 2017

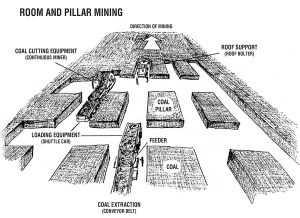

Drawing illustrates “room and pillar” coal mining technique

(Graphic courtesy 0f Illinois State Geological Survey)

Metro East may be at greater risk for mine subsidence than anywhere else in the nation, according to speakers at a special presentation, “Southern Illinois Coal Mine Subsidence: Myths, Facts & Solutions,” sponsored by the Illinois Coal Museum at the Collinsville Memorial Library Center, Nov. 30.

Fortunately, new technologies are emerging to prevent or remediate subsidence damage, according to presentation speaker Dr. Jerry Marino, a St. Louis geotechnical engineer considered one of the nation’s leading authorities on mine subsidence.

However, presentation panelists fear many Metro East business people, home buyers and public officials may still not understand the subsidence risk in the area, or how to assess it.

State law requires insurance companies to include subsidence damage coverage under property-insurance plans in the Illinois 34 Illinois counties deemed to be at risk for such problems, according to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR).

However, presentation speaker Kathy Moran, the industry relations and consumer education manager for the Illinois Mine Subsidence Insurance Fund (IMSIF), fears many property owners may have inadequate coverage or may even waive coverage.

Subsidence has, literally, undermined development across the coal country of Southern Illinois for decades.

In Shiloh, two years ago, subsidence damage at the Dierbergs Green Mount Crossing retail plaza prompted village officials to allocate $8 million to help with remediation costs. Up the road in Fairview Heights, the $4.7 million U.S. Ice Sports Complex was closed in 2012 due to subsidence damage.

Administrators in Swansea’s Wolf Branch School District 113 are currently attempting to determine if they will be able to repair the district’s middle school — which was closed in September after cracks appeared in walls — or will be forced to build a new one at another location.

An architectural firm hired last month to help assess the situation in District 113 was retained by Belle Valley District 119 in 2007 after that district’s north elementary school was damaged by subsidence. Nearby, the Joseph Arthur Middle School in O’Fallon School District 90 is still being monitored for cracks discovered four years ago.

Wolf Branch School District 113’s middle school in Swansea. The administration is reviewing how to proceed on repairing cracks in school walls directly related to mine subsidence. (Photo courtesy of School District 113)

After Benld Elementary School was closed in 2009 due to subsidence damage, Gillespie Community Unit School District 7 was forced to not only build a new elementary school, but backfill an abandoned mine below the district high school to prevent damage there at a cost of more than $25 million.

Mine subsidence refers to lateral or vertical ground movement in man-made underground mines, that directly damages residences or commercial buildings, according to the Illinois Insurance Code.

“In simpler terms, when the roof of a subsurface mine collapses, it causes the ground above to sink or subside,” the IMSIF explains on its web site.

In a commonly used coal mining technique, workers created rooms in a checkerboard or grid pattern, leaving pillars of unmined coal to support the mine roof and the surface, the IMSIF notes.

Metro East is prone to subsidence problems because it lies within the Illinois Basin – a massive, coal-rich geological structure underlying most of Illinois as well as parts of Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Coal veins in the basin lie atop a layer of clay rock which becomes soft and pliable when wet, Marino explains. Wet clay squeezes out from below mine pillars, causing the pillars to settle or even collapse – thereby causing subsidence above. The water seeps into these old workings over time and pool on the mine floor. These mines eventually become completely flooded.

Having worked the vast majority of the coal fields in the U.S., “I would say Metro East has the worst risk in the nation,” Dr. Marino concludes.

Most experts agree that vast areas of room and pillar mines will eventually experience some degree of collapse. However, it may take years, decades, or even centuries, there no way to know when or exactly where mine subsidence will occur.

Although many mines in Metro East date back to the 1800s, there is currently no data to indicate whether there has been an increase in subsidence problems here, Marino says.

The Illinois State Geological Survey (ISGS) has identified numerous areas with active or abandoned mines in Metro East, including:

Clinton County: Beckemeyer, Breese, western Centralia, St. Rose and Trenton;

Madison County: Alton, Bethalto, Collinsville, Edwardsville, New Douglas, Prairietown, St. Rose, Wood River, Worden, the county’s segment of the Monks Mound area;

St. Clair County: Baldwin, Collinsville Freeburg, French Village, Lebanon, Mascoutah, Millstadt, Monks Mound, the eastern New Athens area, O’Fallon, St. Libory, Tilden, and Trenton, as well as that county’s segment of the Monks Mound vicinity.

The Illinois Mine Subsidence Disclosure Act requires real estate sellers to disclose to purchasers all paid insurance claims for mine subsidence on property and the state Residential Real Property Disclosure Act requires disclosure of safety issues associated with property. However, disclosure that the property is undermined is not required.

The IDNR advises real estate purchasers to specifically ask sellers or developers to disclose any information about underground mining or previous mine subsidence claims in surrounding areas, as well as talk with neighbors and nearby business owners regarding subsidence problems. In some areas, the county clerk’s office or zoning board may have information about past mine subsidence incidents.

The Illinois State Geological Survey (ISGS) offers an online Coal Mine Locator, as well as county-by-county maps and directories with the locations of active and abandoned mines. Specialized map and directories for the above-listed localities, with high concentrations of mines, are also available (see www.isgs.illinois.edu/ilmines).

However, the agency warns the maps may not be all-inclusive or perfectly accurate due to a lack of comprehensive mining records in the area.

Damage from mine subsidence may appear suddenly, or develop gradually over time, the ISGS notes. Signs of possible subsidence damage include: cracked, broken or damaged foundations, basement walls, driveways, or garage floors — although such damage may also result from normal ground movement due to changes in soil moisture or seasonal temperature variations.

Property owners who suspect subsidence damage should report a claim to their insurance agent or company, with the date on which the damage was first noticed, according to the ISGS.

Remedial and preventive measures for subsidence damage now range from the new steel band reinforcement technique —recently field tested on a residential foundation in West Frankfort — to high pressure grouting the filing of mine shafts with a particularly fluid form of concrete.

Grouting can be used as a preventative measure. However, it is expensive and generally appropriate only for commercials properties or public works, Marino noted.

Fairview Heights is considering such preventative measures in development of a new industrial tract on undermined land north of I-64. Metro East residents seeking additional information on subsidence risk can contact the Illinois Mine Subsidence Insurance office in Collinsville, telephone (618) 343-0390), or the at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville office of the Abandoned Mines Land Reclamation Division of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, telephone (618) 692-3197).

— Mining subsidence risk in Metro East southern IL may be worst in nation —-