Bootleggers, speakeasies thrived during Prohibition in central Illinois

By Holly Eitenmiller for Chronicle Media — January 29, 2020

McLean County Sheriff J.E. Morrison (far right) in December 1926, with Charles and Linn Morrison, Fred Dryer and John Mangle in front of more than 1,000 gallons of confiscated liquor. (Photo courtesy of McLean County Museum of History)

On Jan. 16, 1919, the 65th United States Congress ratified the 18th amendment, prohibiting the manufacture, sale and transportation of intoxicating beverages. A year later, Prohibition began and gave rise to a nation of rum runners, speakeasies and mobsters.

“Peoria was the ‘Whiskey Capitol of the World’. At peak production, ‘Distillery Row’ along the Illinois River supplied nearly half of the federal government’s entire revenue,” local historian and storyteller Brian “Fox” Ellis said. “There were 73 distilleries and 24 breweries in Peoria before Prohibition, and it all got its start before 1850.”

In 1837, Andrew Eitle established Peoria’s first brewery. Six years later, Almiran Cole built the first distillery and, within decades, Peoria rose from these beginnings to become the largest corn-consuming market in the world.

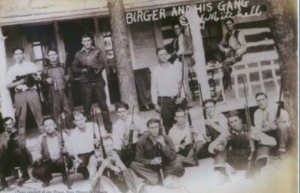

Sothern Illinois bootlegger Charlie Birger (center, sitting on car roof) and his gang at their

roadhouse, Shady Rest, in “Bloody Williamson” County in 1927. The Birger gang had a presence in Central Illinois region as well. (Photo courtesy NIU archives)

With the booze boom came the backlash. The Temperance Movement began in McLean County in the early 1830s, according to the McLean County Museum of History Director of Education Candace Summers.

“Bloomington is credited with being one of the first places in the West to organize a temperance society,” Summers said during a January 16 Prohibition presentation at Bloomington Public Library. “The McLean County Temperance Society started with nine people and by 1840 the society had over 200 members, many of them from the most influential and powerful section of the community.”

Roots of the temperance movement spread through central Illinois by means of similar groups, Sons of Temperance, and reformation groups like The Washingtonians. Peoria, with its battery of distilleries, breweries and pubs, caught the eye of temperance radical, Carrie Nation.

“At the Golden Palace Jefferson Street, the owner Pete Weast adorned the Palace with a painting he purchased in Europe, ‘Nymphs and Satyr,” Ellis said. “It became the focal point of the temperance movement in 1901 when Carrie Nation threatened to destroy the painting with an ax.”

During Prohibition, the O’Neill Brothers served as a local connection for Chicago gangster Al Capone. Booze barrels there were fixed with labels from fictitious companies, and billed as “caustic sodium hydroxide” and other misleading chemicals. The O’Neill Brothers building still stands on Water Street in Peoria. (Photo courtesy of Peoria Historical Society)

Ellis said it’s rumored that Weast paid Nation $50 to spare the painting. Little else was spared by the “dry movements” whose push became so powerful that the efforts of affiliated activists, radicals and lobbyists culminated in the ratification of the 18th Amendment and the ensuing Volstead Act, which enforced prohibition.

“Headlines in the Daily Pantagraph and Daily Bulletin in Bloomington and Normal read, ‘Last Farewells to Barleycorn’ on Jan. 17, 1920 when the 18th Amendment declaring National Prohibition went into effect,” Summers said. “Cities like Chicago and Peoria, known for their breweries and distilleries, were hardest hit.”

What remained of the liquor stores in Peoria were eventually sold illegally and looted, and the underworld liquor business flourished. Federal “dry agents” became a constant presence and raids on speakeasies, social clubs, stills and bootleggers were commonplace.

Peoria broadcaster Greg Batton’s father was 9 when he witnessed federal agents raid a neighboring Pekin home, where the family was running a still.

The building at 353 Court Street in Pekin, directly across from the Tazewell County Courthouse, was a well-known speakeasy during the time of Prohibition.

“A family nearby were running a booze operation in the basement and the feds came in (and) arrested everybody, and everybody knows everybody and they were friends,” Batton said. “They would tear out the boards of the first floors of these homes. These were bungalows, so that the neighbors could come in and walk a plank and look down at the basement at the evil still that the neighbors had put in there.”

Meanwhile, mob operations, run by the likes of Al Capone, Bernie Shelton and Frank Worton, kept the barrels of booze rolling into social clubs and speakeasies around the area. The building at 353 Court Street in Pekin, directly across from the Tazewell County Courthouse, was a popular speakeasy during the 1920s.

That building on Court Street was the home to the Speakeasy Art Center until the organization moved in 2016.

In the basement, ramps remain from when barrels of liquor were brought to the rear of the building and rolled into storage rooms. The door to the speakeasy remains on the third floor and still has what is believed to be the original peephole.

“Violators who went to jail were from all walks of life, including miners, laborers, machinists, soft drink parlor owners, homemakers, draymen, clerks, cooks, farmers, farm laborers, pharmacists and many others,” Summers said. “While the vast majority of those convicted were members of the working class, there were a few cases in which people who held higher class jobs were convicted, such as teachers, small business owners, restaurant owners, real estate agents, city inspectors or even professional entertainers.”

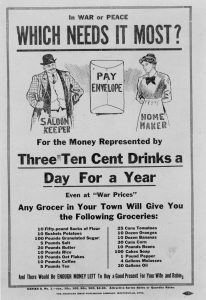

Anti-liquor poster from World War I leading up to the passage of the Volstead Act and Prohibition being enacted. (Library of Congress photo)

Prohibition ended on Dec. 5, 1933, and drinking establishments opened within days of the 21st Amendment’s ratification. Summers said 21 bars opened in Bloomington alone, along with a smattering of others in Normal, which was voted back to a “dry status” less than two years later and remained dry until 1973.

Many other communities remained dry after Prohibition ended. It wasn’t until November 2018 that Goodfield in Woodford County ended its alcohol prohibition. The 85-year-ban was lifted by referendum with a vote of 276 to 145.

“Was Prohibition successful? The answer to this question is yes and no. Prohibition did not work for a variety of reasons. The federal law enforcement system was also completely overwhelmed … prisons across the country began to be filled to capacity … alcohol was still being consumed in mass quantities, prostitution and gambling were still widespread occurrences,” Summers said. “However, Prohibition was successful in some ways. It did reduce the amount of liquor consumed, cirrhosis death rates, admissions to state mental hospitals for alcoholic psychosis, arrests for public drunkenness, and rates of absenteeism in the workplace.”