BICENTENNIAL 2018: Muddy Waters wrote the songs of Chicago’s blues legacy

By Jeff Johnson — June 7, 2018

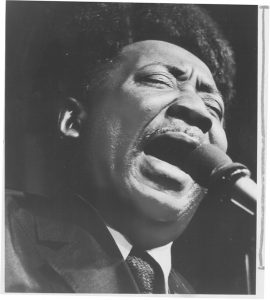

Muddy Waters found stardom with his groundbreaking electric guitar sound and classic bands. (SUN-TIMES FILES)

Since June 2017, Muddy Waters’ image has beamed down from a 10-story mural at 17 N. State St. in Chicago. But the king bee of Chicago blues looms even larger over the city with his outsized musical and cultural legacy.

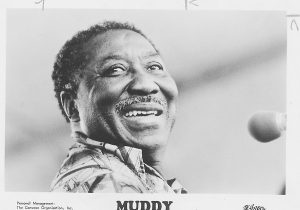

The Mississippi Delta native, born McKinley Morganfield in 1913, followed the Great Migration to Chicago in 1943, where he found stardom with his groundbreaking electric guitar sound and classic bands. He died at age 70 in 1983, but new generations of artists often cite the influence of the six-time Grammy winner and Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, and Waters’ songs such as “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man” and “Rollin’ Stone” are used frequently by filmmakers and advertisers.

International tourists visit Chicago to bathe in Waters’ lore, including a visit to his longtime home at 4339 S. Lake Park. There’s not much to see, though, because the house that Tim Samuelson, Chicago’s cultural historian, has called Chicago’s most historic home has stood vacant and in a state of disrepair for many years. Plans are stalled to convert the Kenwood two-flat into a museum or other attraction.

Muddy Waters’ songs such as “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man” and “Rollin’ Stone” helped earn him a spot in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. (SUN-TIMES FILES)

Waters’ bluesman son Larry “Mud” Morganfield, who like his dad is a singer-songwriter-guitarist, spent time at the house, but never lived there. But he quickly rattles off the names of blues stars who did.

“James Cotton, Pinetop Perkins, Otis Spann and Little Walter all stayed there, and everyone from Paul Butterfield to Keith Richards went there,” Morganfield said. “I don’t care to have that house. What I care about is the house standing and representing Chicago as the real house of the blues. … Chicago needs to keep this man’s legacy alive.”

Morganfield admitted that being the son of a blues immortal can be a double-edged sword from a career standpoint.

“It’s both a curse and a blessing,” he said. “You have people who say, ‘He sounds like his dad, but he ain’t Muddy.’ Of course I’m not. But I have other people come up and tell me, ‘I had a lump in my throat because you remind me so much of your daddy.’ “

A 10-story mural of blues music legend Muddy Waters by artist Eduardo Kobra was completed in 2017 at the corner of State and Washington in Chicago. (Ashlee Rezin/Sun-Times)

Others who want to walk in Waters’ footprints may visit the Chess Studios (www.bluesheaven.com/historic-chess-studios.html) at 2120 S. Michigan, where the bluesman recorded many of his best-known records and rock ‘n’ roll icon Chuck Berry strutted his stuff. Family members of the late Willie Dixon, who penned some of the biggest hits of Waters and fellow Chess artists such as Howlin’ Wolf, operate the studios with their nonprofit Blues Heaven Foundation.

Keith Nelson, Dixon’s grandson, conducts the tours and serves on the Blues Heaven board of directors. He said tours, which cost $10, are given hourly from noon to 4 p.m. Monday through Saturday. He said between 100 and 350 people tour Chess weekly, and many ask about Waters.

“He’s always a huge part of the legacy,” Nelson said. “Muddy would be your most popular artist. He was your face. I’m a big comic book fan, and if you had a blues comic book, Muddy would be your Superman.”

Musicians seeking to capture the Waters mojo may soon have their choice of two recording studios at Chess. “We’re planning to put older recording equipment from 1961 upstairs and modern recording equipment in a new studio downstairs,” Nelson said. “Hopefully this project will be done by the end of 2018 or early 2019.”

Carrying on the legacy of Waters and other postwar Chicago blues greats is the mission of current Chicago blues kingpin Buddy Guy, who once operated the late, lamented Checkerboard Lounge on a section of East 43rd Street renamed Muddy Waters Boulevard. Guy moved Downtown in 1989 with his Buddy Guy’s Legends (www.buddyguy.com), now at 700 S. Wabash.

Buddy Guy at the Chicago Blues Fest in Grant Park. Saturday, June 13, 2015. (Brian Jackson/For the Chicago Sun-Times)

While sweet home Chicago takes pride in its reputation as “the home of the blues,” with a lakefront festival that has drawn hundreds of thousands of music lovers yearly since 1984, the city also is a cornerstone of modern jazz. In fact, Chicago’s jazz fest predates its blues bash by a decade.

King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton were early stars on the jazz scene, and the immortal Louis Armstrong further popularized the New Orleans sound in Chicago in the 1920s. Later Benny Goodman and a host of fellow big-band leaders swung at ballrooms such as the elegant Trianon in the Woodlawn neighborhood and the Aragon in Uptown.

Today the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (www.aacmchicago.org) guides Chicago jazz in adventurous new directions, and the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge (www.greenmilljazz.com), 4802 N. Broadway, builds on its Prohibition-era tradition.

Jeff Johnson is a Chicago-based freelance writer.

Editor’s note: The weekly Illinois Bicentennial series is brought to you by the Illinois Associated Press Media Editors and Illinois Press Association. More than 20 newspapers are creating stories about the state’s history, places and key moments in advance of the Bicentennial on Dec. 3, 2018. Stories published up to this date can be found at 200illinois.com.

—Muddy Waters wrote the songs of Chicago’s blues legacy–