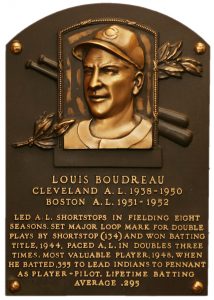

Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau had connections to both Indians and Cubs

By George Castle For Chronicle Media — October 27, 2016 Almost forgotten amid World Series hoopla until a recent newspaper story was the firm link of Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau from the 1948 Cleveland Indians to three decades as one of the most popular Cubs figures around in the broadcast booth.

Almost forgotten amid World Series hoopla until a recent newspaper story was the firm link of Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau from the 1948 Cleveland Indians to three decades as one of the most popular Cubs figures around in the broadcast booth.

The Cubs and Indians, of course, each sought to break unprecedented championship droughts — the Cubs since 1908 and the Indians since 1948. Boudreau ties the two franchises together even more firmly than Cubs president Theo Epstein and Indians manager Terry Francona, who served the Batman and Robin roles together in scratching the Red Sox’s championship itch in 2004.

South suburban Harvey native Boudreau himself is connected with Baseball Barnum Bill Veeck, who had a dual Cubs-Indians identity himself. Veeck, son of Cubs President William L. Veeck, the most dynamic executive in team history, supervised the installation of the famed ivy along with the bleachers and scoreboard in 1937. Nine years later, after returning from World War II Marine service, the younger Veeck bought the Indians, featuring their young player-manager Boudreau.

The “Good Kid” was famous even before his first at-bat with Cleveland. A member of Thornton High School’s “Flying Clouds” basketball team, he helped the school win three consecutive state basketball championships in the mid-1930s. He enjoyed similar success at the University of Illinois as a basketball star while also distinguishing himself in baseball.

The hometown Cubs knew all about Boudreau, but the Cleveland Indians were faster on the draw in signing him to a pro contract before the 1938 season. By 1940, at 23, Boudreau was an Indians star at shortstop with 101 RBIs on just nine homers. He proved so mature, so young, he was appointed Cleveland player-manager for the 1942 season, the second-youngest manager in history after the Yankees’ Roger Peckinpaugh.

Deferred from military service due to arthritis in his ankles, Boudreau starred through World War II, then supervised the break-in of Larry Doby, baseball’s second African-American player signed by the racially progressive Veeck in Chicago in 1947. Boudreau reached his career peak in 1948 just in time to pace the Indians to their World Series title. He batted .355 with 106 RBIs while continuing to manage. He could get his bat on almost any pitched ball, striking out an astounding nine times in 676 plate appearances.

In addition to high honors in a grateful Cleveland, Boudreau got a hero’s welcome in Harvey after the ’48 season. The city gave him a homecoming parade.

By ’48, Doby was an outfield regular, joining yet another Cubs-Indians connection. Right fielder for the title season was the rifle-armed Bob Kennedy, a native of Chicago’s Far South Side. He had started his career on the White Sox as a teen-ager in 1939. Kennedy would go on to become Cubs “head coach” (in reality the manager) from 1963 to 1965, then return as general manager from 1976 to 1981. Doby himself forged a later Chicago connection as baseball’s second African-American manager for the Sox, under owner Veeck, for the last half of the 1978 season.

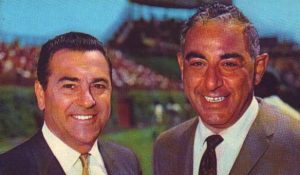

The pairing of Lou Boudreau (left) and Vince Lloyd in the broadcast booth reached new heights of popularity for two decades with loyal listeners all over the Midwest via WGN’s powerful 50,000-watt clear-channel signal.

Boudreau went on to short-term managing stints in the 1950s with the Red Sox and Athletics in the 1950s. After leaving Kansas City following the 1957 season, Boudreau landed the job that would endear him to two generations of Chicago fans. WGN baseball announcer Jack Brickhouse, doubling as the station’s manager of sports, knew Boudreau could talk a good game as manager, so why not use that talent on the air? WGN acquired the Cubs’ radio rights for the 1958 season, hiring Boudreau as the color analyst partner of sparkling play-by-play man Jack Quinlan.

The pairing was an instant hit. Boudreau also had to handle play-by-play for several innings in relief of Quinlan. Thus he found himself at the mic on May 12, 1958, describing Stan Musial’s 3,000th hit at Wrigley Field. He acquitted himself well for a rookie announcer.

One of the funniest bits ever in radio took place around 1963. The Wieboldt’s department store chain was a Cubs sponsor, but did not fine-tune their overall pitch for the male-oriented broadcast audience. So in one campaign, a commercial for the then-new panty hose was given to Quinlan and Boudreau. The pair just broke down in laughter at references to “shadow panels” and such. “Just read what’s on the script,” a teetering Boudreau urged Quinlan. For decades afterward, that tape continued to entertain audiences.

Quinlan tragically died in a car crash in spring training in Arizona in 1965. Boudreau said he would not continue in his job unless baritone-voiced Vince Lloyd, Brickhouse’s WGN-TV baseball partner for the previous decade, took over for Quinlan. The pair had been longtime friends anyway, with Lloyd finding out he could not keep up with Boudreau’s athletic prowess in lunchtime basketball workouts in a hotel gym next to Tribune Tower. Lloyd immediately got the radio job, and the pairing reached new heights of popularity over the next two decades with loyal listeners all over the Midwest via WGN’s powerful 50,000-watt clear-channel signal.

Their style was heartland folksy. Lloyd and Boudreau weren’t above eating fans’ home-cooked specialties sent to the booth while simultaneously talking. They had challenges getting bathroom breaks between innings as many of WGN’s sponsors preferred the baseball announcers do live reads of their commercials.

The famed 1969 Cubs song “Hey Hey, Holy Mackeral” also featured Boudreau’s trademark call, “No doubt about it!” While on play-by-play duty, he would yell “Kiss It Good-Bye!” for a home run. By the 1970s, Lloyd and Boudreau rang a cowbell for Cubs homers.

Boudreau never lost his down-home Harvey accent. He sometimes was syntax-challenged. He entertained the audience with jumbled syllables when (Bill) Madlock batted against (Jon) Matlack. He called supreme Cubs killer Mike Schmidt “Smit” of the Phillies through all his 50 homers in 16 seasons at Wrigley Field.

WGN kept their announcers busy with back-breaking schedules. “An 80-hour week was like a vacation for us,” said Brickhouse. The station did not exempt Lloyd and Boudreau.

Both announcers often were called in do the sportscast on WGN-TV’s 10 p.m. news after working the game in the afternoon. Lloyd also served for a while as Wally Phillips’ morning drive-time sports announcer, reporting to work at 5:30 a.m. while he had an afternoon game on his docket. WGN named the pair the Chicago Bulls’ first radio announcers in 1966, working home games at the International Amphitheater and Chicago Stadium. When baseball season ended, the duo aired a Big Ten football game of the week. And for Blackhawks road telecasts on WGN, Boudreau – who had played club hockey at Illinois – anchored the between-periods shows.

At the height of his on-air popularity, Boudreau reaped his just reward. He was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1970.

Boudreau continued as Milo Hamilton’s radio partner after Lloyd stopped traveling on the broadcasts for the 1982 season. His final full-time radio teammate was Dewayne Staats in 1985.

Boudreau was demoted to home games only when Tribune Co. execs installed former Cubs manager Jim Frey as full-time color analyst/likely spy against the Dallas Green regime in 1987. Frey was rewarded with the GM’s job to succeed Green late in 1987. Meanwhile, Boudreau was retired without fanfare at 70 by WGN management who failed to appreciate his analytical prowess to shift him into another role.

He kept a low profile in retirement, only occasionally visiting Wrigley Field. Boudreau died in 2001 at 84, three years after Brickhouse’s passing and two years prior to Lloyd’s death.

His many fans, posting on Facebook, speculate Boudreau will root for the Indians while Lloyd cheers for the Cubs in the afterlife. If they’re doing the World Series broadcast, it’ll sure be an entertaining one, talking while chewing.

Cubs, Indians players have many local Illinois connections

— Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau had connections to both Indians and Cubs —