Leavitt: Birth, life and death without leaving the house

By Irv Leavitt for Chronicle Media — April 17, 2019

Amy Webb is the author of “The Big Nine,” a very scary book about artificial intelligence. (Elena Seibert Photography)

I spent much of my free time early this month being terrified by a new book about artificial intelligence that predicts the death of me and everyone I know.

Amy Webb is a prominent sciencey person, so I don’t know why everybody isn’t all up and arms about her book’s view of the future. But then again, the east and west coasts are expected to go underwater before too much time passes, and that doesn’t seem to worry most people overmuch, either.

Webb maintains in her artificial intelligence book, “The Big Nine,” that before too long we will all have little robots called nanobots swimming around in our bodies. They’ll be able to fix just about everything that goes wrong with us, health-wise.

Unfortunately, however, she expects that if we don’t watch out, the Chinese will take advantage once they need our stuff. They’ll hack our nanobots and we’ll all die.

This is bad news for those of us who want to go on living. Therefore, I started spreading the word to my friends, when the jukebox wasn’t playing too loudly for them to hear.

Every time I tried to explain, I got stopped at the nanobot part.

“Ugh. Oh no, I’d never let people put little robots in me.”

This I do not actually believe. I think people will jump at the chance at ingesting robotic parasites or anything else that reduces their trips to doctors.

That’s not just because doctors pick on us about our weight and lack of exercise, and do things to us that hurt.

I think people dislike going to doctors because it’s a pain in the neck to get an appointment, and then, when they finally get one, they actually have to go.

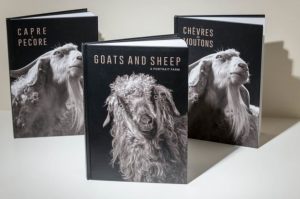

A new book featuring portraits of sheep and goats is available in multiple languages. (Kevin Horan photo)

More and more, people avoid going to places that are not fun.

While riding on a bus this week, I met a nice young lady who said she has most of her nourishment delivered because, “When you don’t have a car, it’s amazing how hard it is to do things, even just getting groceries.”

She added that her spouse has a car. Apparently, he isn’t into the helping-out thing.

It occurred to me later that this news about how hard it is to get around came from a person then on the last leg of a public-transportation journey of about 60 miles for a social call in a different county.

An old friend of mine, Kevin Horan, spent decades on arduous and perilous journeys laboring as a skilled news photographer. Like most journalists, few people beyond a select group of relatives knew who he was.

But Horan is suddenly getting famous for a new book that’s very different from his previous work.

“Goats and Sheep: A Portrait Farm” is filled with pictures of the aforementioned creatures.

Wild goats are hard to photograph, because they like to hang out on the sides of mountains and in trees, even. Sheep are a little easier to pin down, but they’re still a challenge if unteathered. When enthusiastic, they jump sideways, which makes great video, but it’s challenging for stills.

Horan’s subjects were not in their natural habitat, he makes clear. They were shot in front of a black screen, usually while handlers held them on leashes.

The pictures are headshots, like the ones insurance agents get for their business cards. They even look like insurance agents, because goats and sheep have large features and facial fur that tend to give them the appearance of conniving old men.

Most people find the pictures fascinating, in a similar way that we find pictures of the faces of dogs and cats fascinating. But this is different, because they’re goats and sheep.

Horan came to town recently for a bookstore talk on his goats and sheep book. The place was packed, with a lot of the attendees fellow photographers. Every book on hand was sold.

I think only half the reason was the quality of the pictures. The other half was respect for Horan’s invention of a new kind of product.

Sean Sandona’s Doorage storage buildings are clean and tidy, but customers never see them. (Photo by Irv Leavitt)

“Kevin, let me get this straight,” I said, interrupting his book signing. “You didn’t have to chase these animals up mountains and into trees? You went over and shot them like kids dressed up for school pictures?”

He grinned broadly, catching my meaning. “Yep, and the barn was less than five miles from my house,” he replied.

“This is a genius racket,” I said with admiration.

Horan’s faces-of-animals idea is attractive in an economy increasingly dedicated to doing as much as possible without leaving home. Even five miles, one day, may seem like a long commute for this kind of work.

I expect that laid-off news photographers living in rundown studio apartments are right now pointing sophisticated lenses into their kitchen cabinets to see if roaches’ faces remind them of anybody.

I’ve remained more mobile than a lot of folks. I still do all my own grocery shopping, and buy most of what I need in person. But one place I hate going is my self-storage locker.

Walking down those lonely steel corridors, with the lights snapping on at my approach, is only slightly cheerier than visiting a police lockup.

But in the last few years, there’s a new model. Customers pack their stuff in bins, and the storage companies come out and pick them up. They come back when you want the stuff again. You don’t ever have to go. They don’t want you to go.

One of the fastest-growing businesses of the new type is the Chicago-area-based Doorage, operated by Sean Sandona, who says he is taking the new trend to the next level.

He charges by the cubic foot, so he can efficiently sock away mattresses, television sets and barbecue grills as well as the stuffed bins. He promises not to raise prices on customers unless they cancel, and charges only $20 for a pickup.

Best yet, next year, customers will be able to, with the push of a button, order him to sell or junk their stuff. That way, they can easily get out of the fix that is part and parcel of self-storage: paying for years to store something you never should have acquired in the first place.

Doorage, after next year, can make it all disappear with the tap of a key.

“We will have solved the self-storage trap,” Sandona said proudly.

There are other businesses that operate similarly. You can buy a mattress online, and have the old one taken away. If you don’t like the new mattress, you have a month or so to replace it online with another model. Then when that’s worn out, start over, without ever getting out of bed until the guys ring the doorbell.

I occasionally see Russian and Southeast Asian women advertised as sort of instant girlfriends or wives, I’m not sure which, online. Pretty soon, that whole process might be completely arranged without stepping outside, too.

After the lady arrives, a marriage license can be downloaded, signed, scanned and filed, and a preacher can be summoned over Skype to finish the job.

The happy couple can live and work at home, and their future children go to online school.

When the email-order bride gets old and feeble, another button summons a paramedic van, and off she goes to the nursing home. Later on, a button sends her to her reward.

Unless the nanobots get her first.