Empty chairs remember lives cut short

By Kevin Beese Staff Writer — September 26, 2023

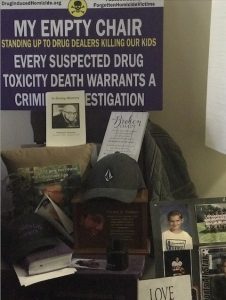

Mary Ann Haim’s chair is a tribute to her son, Patrick, who died from a fatal drug consumption in 2019. (Photo provided by Mary Ann Haim)

Second in a series looking at drug-induced homicides

The picture of a young, smiling baseball player, dressed in his Glendale Heights White Sox jersey and hat, has an overlay proclaiming “Patrick Haiman Taking the Team to Victory.”

That picture is pinned to posterboard that sits in his mother’s apartment just feet from the memorial program that remembers his life against the foe he could never beat — addiction.

“I took him to the emergency room more times than I can count,” his mother, Mary Ann Haiman, said.

Still, it was not his dependence on drugs that took his life in 2019 in an Addison apartment, but a fentanyl-laced drug that he took.

Another mom who lost a child to an overdose asked Mary Ann Haiman for a copy of the toxicology report done after Patrick’s death.

“She looked at the report and said, ‘Your son did not overdose. He was murdered. He had enough fentanyl in his system to kill a dozen guys.’”

A chair with memories of Patrick Haiman sits outside Mary Ann Haiman’s Glen Ellyn apartment as part of the weeklong My Empty Chair campaign, remembering lives lost to drug overdoses.

Mary Ann Haiman said she is unclear why her son relapsed, even putting himself in the position to take a fatal dose.

“He had been clean. He graduated from DuPage drug court,” Haiman said. “Why did he use? No one will ever know.”

She said no one was ever held responsible for her son’s death.

“Justice was not done,” she said.

Haiman said law enforcement was initially looking at her son’s death as a drug-induced homicide because evidence showed he took a Lyft to Bellwood to get the drugs.

However, after days of law enforcement and a Smart phone expert not being able to unlock Patrick’s phone, she was able to do so. She rushed the phone back to law-enforcement officials.

“An officer called the dealer and pretended to be Patrick. The dealer had already been told about Patrick’s death and dumped the burner phone,” Haiman said. “The investigation was over.”

After her son’s death, Haiman felt called to help others. She got a job as a substance abuse counselor shortly after Patrick’s death. She works at a Stone Park methadone clinic. At 70 years of age, she is about to become a certified counselor.

“I do it in his honor. I save lives for him,” Haiman said. “I tell his story every single day.”

Alyssa Cordoza

Brenda Sturgeon said she has not gotten anywhere in trying to get people charged in connection with her daughter’s overdose.

“They’re writing her off as a drug addict,” Sturgeon said. “She used drugs, but she did not want to die.”

Sturgeon’s daughter, Alyssa Cordoza, had heroin and four different kinds of fentanyl in her system, according to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office.

“I was hoping the Medical Examiner’s Office was going to say ‘murder,’ but they said, ‘accidental overdose,’” Sturgeon said. “If someone puts something in your drink, they can be charged with murder. The same should be done for people adding fentanyl to drugs.”

She said her daughter’s death in Bridgeview not being looked at criminally is infuriating.

“Nobody is pursuing it. I had faith in the system, but I lost all my faith,” Sturgeon said. “I don’t trust what they say.”

An empty chair sits outside Sturgeon’s Oak Forest home this week in memory of Alyssa. A picture of the then-25-year-old woman is in a sign holder. A sign calling her murder “a drug-induced homicide is part of the display remembering Alyssa as are an angel statute and a pair of angel wings. A purple — the color used to recognize overdose poisonings — light illuminates the display.

“It’s growing every year,” Sturgeon said of the Empty Chair campaign. “More and more people are doing the empty chair.”

Sturgeon, who is a representative for the Illinois Chapter of the Drug-Induced Homicide Foundation, said the annual display she creates draws attention to the issue.

“People stop and read the sign. Even police drive by and stop and read the sign,” she said. “It is increasing awareness.”

Sturgeon noted that more than 300 people per day die in the United States from drug-induced homicides. Most of the deaths are fentanyl-related, she said.

She said that police didn’t collect evidence when Alyssa was found dead.

“Her phone was dumped. The call log was emptied,” Sturgeon said. “Police never even bothered to look at her phone.”

Sturgeon said it is her hope that her fighting for the cause gets things done.

“I would like to have everyone start using the drug-induced homicide law; and I would like people to have awareness of fentanyl,” she said.

Sturgeon advised young adults to reject taking any kinds of drugs.

“Don’t do any drugs,” she said. “Don’t take drugs from anyone unless they are prescribed for you or given to you by a parent.”

Ashley Parkinson

Sara Parkinson is still perplexed by the circumstances surrounding her daughter’s death in 2016.

“She used to yell at her younger sister about smoking pot,” Parkinson said.

So, when the toxicology report came back showing Ashley Parkinson had heroin in her system at the time of her death, her mother was stunned.

“She never did drugs. There were no needle marks found on her during the autopsy,” Sara Parkinson said. “There was no alcohol in her system.”

She believes that someone may have slipped a tiny bit of heroin into her daughter’s soda that night at a Bridgeview trailer park party and that the small amount of heroin was too much for the slender 19-year-old to handle.

Not having answers seven years after her daughter’s death is tough to handle for Sara Parkinson.

“It is very frustrating. It’s every parent’s worst nightmare,” Parkinson said.

An empty chair sits outside Parkinson’s Bridgeview home this week, remembering her daughter.

“It helps advocate for drug-induced homicide charges,” she said. “It is not going to bring her back, but it lets other people know there is an issue.”

Parkinson said she still hangs a stocking for Ashley every Christmas and there is a lantern placed on a table with a small rocking chair in memory of Ashley every year.

“She made us parents. She was the first grandchild,” Parkinson said. “She was the sweetest person you’d ever meet.”

The Bridgeview resident said she goes to the cemetery and decorates Ashley’s grave for the holidays and during the summer.

“I go there, but I think she’s not there, she’s in heaven,” Parkinson said. “I think she should be alive and traveling the world right now.”

Parkinson said that when it was determined there was no fentanyl in Ashley’s system, Bridgeview police said they could not trace the drugs to the West Side of Chicago, and therefore there would be no investigation.

She said law enforcement and prosecutors need to hold those who sell fatal drugs to others liable for those deaths.

“If you give a pain pill to somebody, you can be liable for their death,” Parkinson said. “If a bartender overserves somebody, he can be held liable.”

Parkinson said young adults need to be aware that using drugs even one time can be fatal.

“One time can kill,” she said.