ISU Math Professors Discover Missing Pages from Abraham Lincoln’s Ciphering Book

June 19, 2013

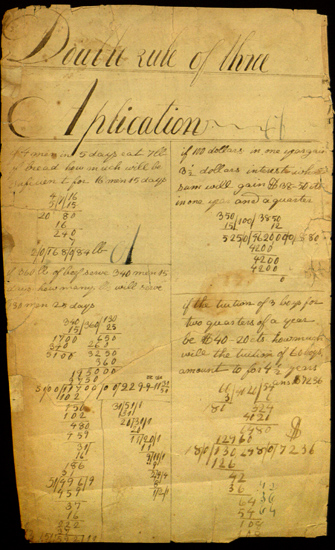

This?photo?illustrates?the?page?from?Abraham?Lincoln’s?ciphering?book?that?ISU?math?professors?Nerida?Ellerton?and?Ken?Clements?discovered?at?the?Houghton?Library?at?Harvard?University.?Photo is provided courtesy?of?Houghton?Library,?Harvard?University.

NORMAL — In 2009, Nerida Ellerton and her husband Ken Clements, both professors in the Department of Mathematics at Illinois State University, were very excited when they discovered, in the archives of the Houghton Library at Harvard University, a leaf comprising two pages from a ciphering book prepared by a teenage Abraham Lincoln.

Originally, the couple thought the leaf was one of 10 known surviving leaves from the ciphering book.

“We were searching in various U.S. archives for ciphering books prepared by North American students in the 1700s and early 1800s” said Ellerton. “When we were at Houghton Library we were not looking specifically for anything prepared by Abraham Lincoln, but this leaf came up with Abraham Lincoln’s name on it. At this point, we assumed that this leaf would be well known to Lincoln historians.”

But somehow, it had been missed. After reviewing the 10 surviving leaves illustrated in the book “The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln,” which the Abraham Lincoln Association published in 1953, the couple realized that the leaf that they had found at Houghton Library was a hitherto unknown leaf from the ciphering book prepared by Lincoln in the early 1820s when he attending school in Indiana.

“Our major role was to identify the leaf as coming from Lincoln’s ciphering book,” said Clements.

A letter written in 1875 by William Herndon, Abraham Lincoln’s law partner, was filed with the leaf at Houghton Library. In the letter, which establishes the authenticity of the leaf, Herndon stated that he had obtained Lincoln’s ciphering book from Lincoln’s stepmother after the 16th President of the United States was assassinated.

Clements said that Herndon gave leaves from the ciphering book to different people.

“They were scattered all over the nation,” said Clements.

Ellerton and Clements announced the discovery of the missing leaf during a news conference that was held earlier this month at Illinois State University. The announcement was a combined statement from Illinois State University, Harvard University, and the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield.

Ciphering books were handwritten books that students created in school while learning mathematics. The eleventh leaf which Ellerton and Clements found shows Lincoln’s solutions to tasks concerned with the “Double Rule of Three”—and according to Ellerton, that was a level of math never reached by many students in the 1820s.

Later Lincoln tended to understate his school mathematics achievement. In 1859, he indicated that at school he had ciphered to the “Rule of Three,” but in fact he went beyond that. It is possible that he made this understatement for political reasons— he wanted to project himself as a rail-splitter, as someone who could relate to “ordinary people,” said Ellerton.

An example of a problem that Abraham Lincoln solved on the leaf is: If 100£ in 12 months gained 7£ interest, what principal will gain 3£-18S-9d in nine months?

After discovering the eleventh leaf, the couple determined the order in which the 22 pages remaining from the ciphering book were likely to have been written, said Clements.

“Other scholars had attempted to do that with the 20 pages, but our order is different,” said Clements. “We know the order in which people studied arithmetic topics at that time because we’ve studied ciphering books extensively.”

According to Ellerton and Clements, Lincoln’s calculations were usually very accurate, and he clearly knew what he was doing when he solved mathematical problems.

“We went over everything that he did and except for a couple of small slips here and there, he didn’t make any errors,” said Clements. “He was amazingly accurate.”

Some scholars have mistakenly claimed that Lincoln often made errors in his ciphering book, but in fact he did not, said Clements.

“We checked what some have said were errors and found that Lincoln was right on every occasion,” said Clements.

The couple believes that Lincoln’s ciphering book originally had about 16 leaves or 32 pages. They think that it is unlikely that any additional leaves will be found.

“We don’t reject the possibility that there are other pages out there,” said Clements.

The Houghton Library at Harvard University owns the leaf that the couple discovered. Other universities and institutions throughout the country own 8 of the other 10 leaves, and 2 of them are in private hands.