Turn of the Century Artist Still Relevant

April 9, 2014

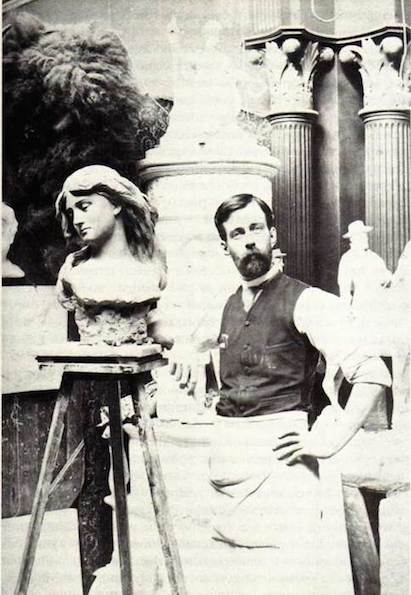

Lorado Taft sculpting. Photo courtesy of the Fine Arts Society of Peoria.

If you have ever lived in or visited Chicago, you may have heard of a man called Lorado Taft. Even if you spent 30 years living in the Windy City and have never heard his name, you have undoubtedly seen one of his many sculptures that not only make up the city but also say something about it during Taft’s time and even today.

This influential man is the subject of a lecture hosted by the Fine Arts Society of Peoria that is taking place on April 10 in Peoria.

Taft was born in Elmwood, Ill.; grew up and went to college in Champaign, obtaining his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Illinois; and spent three years studying sculpting at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, the National School of Fine Arts in Paris before returning to the United States and settling in Chicago in 1886.

While he has sculptures scattered all across the United States, most of his work – such as “The Fountain of Time” in Chicago’s Midway Plaisance, “The Fountain of the Great Lakes” at the Art Institute of Chicago and “Alma Mater” at the University of Illinois in Champaign – is located in Illinois and Chicago in particular.

Lecturer and writer Wendy Greenhouse, who holds a doctorate in Art History from Yale, will review Taft’s life and diverse career as a sculptor, educator, lecturer, and supporter and promoter of the fine arts.

“The [primary] focus of my talk really is about how Taft’s practice on all these different levels aligned with what he and many of his contemporaries perceived as cultural needs in Chicago at the turn of the century – the need for uplift, the need for beauty, the need for people to be more closely connected to the creative impulses in themselves and in the world around them,” Greenhouse said.

“I’m very interested in how Taft saw his art as something by which he could reach people and really transform their lives,” she added.

By working with educators, architects and social reformers, Taft wanted to address what he and many of his contemporaries saw wrong with Chicago, what they thought it lacked and what it needed, Greenhouse says.

The lecture will be from 10-11 a.m. this Thursday at the Anshai Emeth building located at 5614 N. University St. Tickets are $10 for adults and $5 for students and can be purchased at the door. For more information about the event, tickets or the FASP, you can call the organization at 309-693-7600.

For those who want to go further than the lecture, the FASP is hosting a trip on May 8 to the Anderson Gardens, which was part of a previous lecture, in Rockford and to Oregon, Ill. to view some of Taft’s sculptures in a self-guided tour. Lunch will be provided.

You can get more information about the trip by calling the FASP.

Although he taught at the Art Institute of Chicago, Taft’s teaching was not limited to traditional university sculpting students. He influenced and supported the artwork of office workers, stenographers, car company employees and numerous others in various professions.

It was part of his desire to bring fine art to more than the average Art Institute exhibition attendee. He wanted to show the everyday citizen that art had something for them, as well.

“It came over me gradually that the coy attitude of our artists, like a girl waiting to be proposed to, was not a success [and], that while our public needed sculpture, it did not know it and would never guess it until someone showed it what it wanted,” Taft was once quoted as saying.

He was also a believer in the woman artist during a time when it was not fashionable to let women sculpt. A group of his women students known as the White Rabbits even went on to become successful artists in their own right.

This practice of supporting the uncommon artist stretched to his prolific lecturing, where he would speak at expected places like the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois but also at less elite places like certain women’s clubs.

During certain lectures, he would use clay to demonstrate certain techniques and processes while talking about the larger ideals of sculpting and art.

He was possibly even one of the Midwest’s most well-known names in the art world in his day.

Even though his name was everywhere during his day, it is hard to judge how many people at the time would have known about him, Greenhouse says. She is sure, however, that if you were a relatively active, middle-class person who read the newspaper and was interested in what was going on in the city culturally, you would have known about him.

That public awareness has changed over the many decades since his death in 1937. Taft did the work of six artists in his one lifetime, but he is not thought of by many people today, whether they be an average person or a sculptor. Part of that has to do with his style, which many modern sculptors do not study anymore, Greenhouse says.

Taft wanted to make sculptures that were more imaginative, allegorical, metaphoric and that were about ideas as opposed to just honoring people according to the styles of his day.

On the surface, his art seems quite conservative, old fashioned, traditional and not in line with the more modern styles of today, Greenhouse says. This turns many people off, because they think the sculptures have absolutely nothing to say to them in the present.

“I’ve talked about Lorado Taft, [and] I’ve used his pieces with students,” Greenhouse said. “When people know something about it and give it a chance, they really enjoy it, and they don’t see it as irrelevant. They understand that Taft was addressing big themes [and] big ideas that are still relevant today.”

Greenhouse believes we are surrounded by overlooked art that influences us and is part of our lives. One example she uses is the painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware.” It is an extremely popular, widely seen and influential piece that is part of who we are and says a lot about us, but most people would be incapable of naming the painter, Greenhouse says.

“This is one of the reasons why I in particular am so fascinated by artists like Lorado Taft,” Greenhouse said. “My whole career, I’ve been really interested in artists who were once toweringly obvious and influential and revered [but] whose names have really kind of gone underground for all kinds of, I think, pretty obtuse reasons.”

“Their work is still important, and it’s certainly historically important,” Greenhouse added. “It’s impossible to write the history of Chicago’s artistic or cultural life at the turn of the 20th century and not talk about Lorado Taft. He’s just too important on too many levels.”

Greenhouse would like people to walk away with not just a great understanding of Taft’s work but a better appreciation for the role of art in today’s cities.

“We still have a lot of the same problems in our cities, and we still need art and beauty not to lift us out of those problems and make us forget but to give us some tools for addressing them on the deepest level,” Greenhouse said.