How criminal justice bill would overhaul officer certification

By Raymon Troncoso Capitol News Illinois — February 1, 2021

SPRINGFIELD – A criminal justice package that passed both chambers of the General Assembly last month contains provisions that would grant the state increased power over police discipline and standards of conduct starting in 2022.

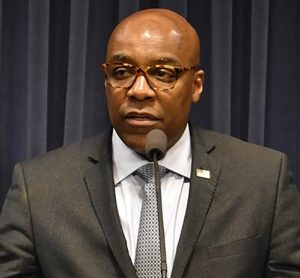

The omnibus package, which was backed by Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul, has not yet arrived at the desk of Gov. JB Pritzker, although he has said he looks forward to reviewing the bill which needs only his signature to become law.

Pritzker campaigned on several issues in the bill and indicated his support, but has not yet said directly that he will sign it.

One of the more controversial provisions in the bill would expand the scope of the Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board, or ILETSB, which currently oversees training and grant programs for law enforcement and correctional officers throughout the state.

Police certification standards would be made more robust under the legislation, with law enforcement officers placed into three categories: active, inactive and decertified. Only those with an active certification from ILETSB can be legally employed at an Illinois agency in a law enforcement capacity.

A decertified officer has 30 days to file a motion with the board for reconsideration, and all decertifications are subject to judicial review. Once an officer is formally decertified, they are prohibited from ever regaining certification.

Each officer will be responsible for keeping their certification active by submitting verification forms to ILETSB every three years to confirm they’ve completed all mandatory training and have no disciplinary actions taken against them that would result in decertification.

Under current Illinois law, officers can only lose their certification under very narrow circumstances. They must either be convicted of a felony or a limited list of “decertifiable misdemeanors” such as offering a bribe, theft and prostitution.

From 2009 to 2014, Illinois decertified 64 officers. Over the same period of time, Florida decertified 2,125 officers and Georgia decertified 2,800.

Raoul, in his testimony in House committee in support of the provision during January’s lame duck session, told lawmakers that while he does believe Illinois has the best trained and most upstanding law enforcement in the country, the massive discrepancy in the numbers has more to do with how hard it is to fire and decertify officers for blatant misconduct, even if the officers were known to be repeat offenders.

The new law would grant ILETSB broader discretionary authority to decertify officers that violate the new standards of conduct.

If the board determines an officer committed a felony or “decertifiable misdemeanor” that would normally result in automatic decertification, but the officer has not been charged or convicted, it can decertify that officer through the discretionary process.

Other misconduct that can result in discretionary decertification includes excessive force; failing to intervene in another officer’s use of excessive force or failing to render aid; tampering with dashboard and body cameras or their footage; committing perjury or making false statements in an investigation of a crime; and engaging in any unprofessional, unethical or deceptive conduct harmful to the public whether or not it caused actual injury.

While governmental agencies are required to submit violations to ILETSB within seven days of their occurrence, the provision would also allow for members of the public to submit a complaint about an officer, and they may keep their own identity confidential as well.

Decertification process

Opponents of the bill have claimed the ability to file complaints anonymously will result in officers being targeted by disgruntled citizens and criminals who will flood the system to get them fired.

Raoul contends the provisions of the bill prevent unwarranted termination by filtering complaints through several layers, and that confidentiality is important to preserve the integrity of the process.

“We have to realize there have been incidents throughout the country that make the public at large feel that they can’t have the greatest level of trust in law enforcement and we have to restore that public trust,” Raoul said in an interview with Capitol News Illinois last week. “Just like other professions where they may be whistleblowers that their identity is protected such that there’s no retaliation against them, but that doesn’t mean you don’t investigate the allegation thoroughly.”

When ILETSB receives a complaint about an officer, it will conduct a preliminary review to determine if there’s enough information to investigate. If the review finds there’s sufficient cause, the board will conduct a full investigation.

If the board’s investigation determines the officer may have conducted decertifiable conduct, it will submit a formal complaint to the Illinois Law Enforcement Certification Review Panel, a new entity created by the legislation with 11 members appointed by the governor and attorney general.

The complaint will result in a formal hearing before an administrative law judge who will hear the allegations in the complaint and testimony from the officer, their legal representation and relevant witnesses to the case. The judge will then deliver their conclusion and a recommendation to the panel.

The panel then votes on whether to recommend ILETSB remove the officer’s certification or dismiss the complaint, with a simple majority vote needed either way. The recommendation is nonbinding.

Then, and only then, can ILETSB choose to decertify an officer through another majority vote.

Outside of this process, an officer’s certification can only be revoked if they’re convicted under the current decertification standards or rendered inactive if the officer fails to submit a valid verification form to ILETSB during their required reporting period.

Transparency database

The legislation also requires ILETSB to enhance transparency, both within law enforcement and for the broader public.

The Professional Misconduct Database, a private portal for chiefs and sheriffs, will be expanded and streamlined for all relevant governmental agencies, law enforcement entities and state’s attorneys. The portal will contain an officer’s certification history, reported instances of misconduct, suspensions and terminations.

Any agency looking to hire an individual in a law enforcement capacity would be mandated by law to view the individual’s entry in the database before offering employment.

ILETSB will also create and maintain two new searchable public databases in an accessible portal on their website. One will contain officers’ agencies, their certification status and confirmed instances of misconduct that led to decertification. The other will contain all completed investigations against law enforcement and correctional officers with any identifying information of the officers involved redacted.

The attorney general’s office will also have greater latitude to investigate systemic abuse in law enforcement agencies under the new provision. According to Raoul, his office can only do so under the current law if the abuse is a clear human rights violation based on race, gender, national origin or other protected classes but not if it is a general systemic issue.

Potential ‘clean-up language’

Republicans and law enforcement groups have voiced fierce opposition to the criminal omnibus legislation as a whole, urging Pritzker in a recent news conference to veto the bill once it arrives on his desk.

On police certification, Republican lawmakers take issue with the unfunded mandates involved in the new system and mandatory trainings for officers. The bill goes too far without providing more funding for police departments, they said, especially as the state is already hurting for revenue due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the continued structural budgetary pressures.

The bill’s sponsors in the General Assembly, Chicago Democrats Sen. Elgie Sims and Rep. Justin Slaughter, have indicated budgetary issues and clean-up language can be addressed in follow-up legislation in the new session, which is why the bill’s effective dates are pushed back by a year or more instead of being effective immediately.

A release posted to the ILETSB website the day after the legislation’s passage reads “we have asked for our appropriations to be increased and funding secured to accommodate the increased trainings and duties associated with processing certification verifications, investigating statewide complaints, and seeking the decertification for reported misconduct.”

It continues, “we trust that in the upcoming months, discussions on this topic will be fruitful.”

Despite opposing the broader bill, law enforcement has been supportive of the certification provisions. Starting in June, the Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police, the Sheriff’s Association and state’s attorneys collaborated with the office of the attorney general and the governor’s office to craft the language. According to Raoul, the group met nearly 20 times.

“We were trying to work with the attorney general on this,” Joe Moon, president of Illinois Troopers Lodge 41, said at a Republican news conference. “However, before that could happen this was all rammed together and shoved out in the lame duck session for a vote.”

While police certification was originally its own legislation, it was added to the criminal justice reform omnibus package on the final day of the lame duck session.

“With regards to people urging the governor to veto, I welcome discussion about specific elements of the bill and where there might be need for a follow-up, clean-up language and so forth. I think that is a healthy part of the legislative process,” Raoul said. “My participation has been to negotiate in good faith and to have the input of law enforcement along the way.”

rtroncoso@capitolnewsillinois.com