Milking Medicaid: Insurance firms reap in billions while doctors get stiffed

By David Jackson and Kira Leadholm Better Government Association — November 22, 2021

The investigation found hospitals were forced to turn away thousands of patients because the MCOs routinely deny, delay and reduce reimbursements to providers who treat low-income families, foster children, pregnant women and the elderly.

State-contracted insurance firms balk at paying frontline medical providers, threatening the viability of leading hospitals and clinics, and imperiling Illinois’ entire Medicaid program.

The privatization of Illinois’ health care system for the poor has shifted hundreds of millions of dollars in profits to insurance companies and away from frontline medical providers, a Better Government Association investigation has found.

The four-month examination — including dozens of interviews and a review of thousands of previously unpublished documents — reveals a system largely bereft of government oversight in which for-profit insurance companies routinely deny, delay and reduce reimbursements to providers who treat low-income families, foster children, pregnant women and the elderly.

The result is a state Medicaid program run as an insurance industry profit center, while service for the needy falters. The four nationwide insurance companies — called managed care organizations, or MCOs — last year were paid a record $16 billion from taxpayers.

The financial strain on frontline health care providers — along with the state’s failures to intercede on their behalf — has prompted thousands of complaints to state officials and lawsuits alleging the MCOs’ pursuit of corporate profits have put many providers on the edge of bankruptcy.

Those most severely affected are the state’s 3 million Medicaid recipients. Hospitals say they were forced to turn away thousands of patients. Group homes for disabled adults were shuttered, programs for drug addicts were cut and ambulance drivers were laid off, according to government records filed by medical providers.

Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services Director Theresa Eagleson, who took over the agency in 2019, acknowledged the conflicts and said she has taken steps to mediate complaints and more effectively steward taxpayer money.

Eagleson said her predecessors’ rapid push to complete privatization created growing pains in one of the largest expenditures in state history. Now, her administration is convening regular summit meetings and building systems to more rapidly mediate disputes.

Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services Director Theresa Eagleson. (Illinois.gov)

“We have really tried to change that paradigm, and I’m hearing from some of the same people that it’s working,” Eagleson said. “I’m hearing from legislators, I’m hearing from providers, I’m hearing from trade associations: It’s not perfect, but you’re listening, and we can tell you’re trying, and gosh we appreciate it. It is really changing.”

Frontline Medicaid providers agree the new initiatives are positive steps, but they are skeptical whether it’s enough to balance a playing field pitting giant insurance firms focused on their bottom lines against local practitioners who say they put mission before profits. They also complain about the executive revolving door between the state’s watchdog agency and the insurance companies they are supposed to be watching.

“This is a broken system,” said Michael Sunderland, director of accounts receivable at Chestnut Health Systems, a 700-employee mental health treatment agency based in central Illinois.

“Reimbursement issues seem to be a part of the MCOs’ business mode — deny, delay and don’t pay,” Sunderland said. “When that happens, patient care is impacted, and it’s not just at one organization.”

Problems threaten the viability of Illinois Medicaid

The Illinois legislature began to privatize Medicaid in 2011 under then-Gov. Pat Quinn, a Democrat. Officials promised to save taxpayer dollars, improve care for low-income patients and give them more choices when selecting doctors and clinics. Before then, the state paid each doctor, clinic or hospital a fee for every Medicaid service rendered.

The privatization accelerated under Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner in 2018 and was embraced by current Gov. J.B. Pritzker, a Democrat.

Under their current contracts with the state, four for-profit MCOs are supposed to quickly reimburse practitioners who care for Medicaid patients. Medicaid rules say the MCOs must pay 90 percent of providers’ uncontested claims within 30 days and 99 percent within 90 days.

But many providers allege the MCOs deploy bureaucratic dodges and opaque billing error codes to skirt the federal rule, make partial payments, pay years late or deny claims without explanation.

A BGA analysis examined several years of “quarterly statements” the four state-contracted MCOs are required to file by the Illinois Department of Insurance.

During the first six months of 2021, three of the MCOs — Meridian Health Plan of Illinois, Aetna Better Health of Illinois and Molina Healthcare of Illinois — reported a combined total revenue of $5.2 billion from their Illinois Medicaid contracts, from which they took $294 million in profits.

Those profits did not include hundreds of millions of dollars in management fees the MCOs paid to their parent companies, Centene Corp., CVS Health and Molina Health, respectively. None of those firms responded to BGA requests for comment.

The fourth for-profit Illinois Medicaid contractor — a subsidiary of insurance giant Blue Cross Blue Shield — includes figures from four other states in its quarterly reports, preventing a comparison. It reported net profits of $1.5 billion during the first six months of this year.

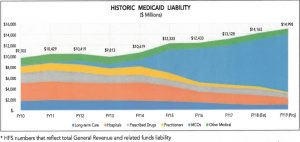

This chart from the Illinois Comptroller shows the amount spent on Medicaid Managed Care Organizations. It does not include the $16 billion spent last year. (Source: Illinois Comptroller)

“We work hard to help ensure that providers receive prompt payment for covered services rendered,” Blue Cross Blue Shield told the BGA in a statement. The insurer also provided a lengthy list of programs and grants it sponsors in communities throughout Illinois, “helping close the gaps that present barriers to people’s health.”

As anger about billing shortfalls grew among frontline Medicaid providers, Eagleson’s health agency in 2019 set aside $46 million for a new computer clearinghouse to track provider claims and mediate billing disputes.

In documents the department used to justify the need for the clearinghouse, HFS said lawmakers were “alarmed” by MCO reimbursement denials to frontline Medicaid practitioners.

“It is unclear what the root cause of these denials is, and HFS has no insight into the claims transactions,” HFS officials wrote. “Failure to address the cause of these denials threatens both the viability of some providers and the viability of the managed care program, which is designed to save the state hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Eagleson said she hopes the $46 million clearinghouse will be fully functioning by the end of this year.

“We’re still working to bring it to full operational capacity,” Eagleson said.

Costly complaints and lawsuits

To evaluate whether health care providers were being denied reimbursements unfairly, the BGA examined internal state reports, court depositions and correspondence between state officials and hospitals, clinics and doctors.

Among examples found by the BGA:

HFS Manager of MCO Operations Laura Ray Gumble and other HFS officials were asked in court depositions what they do to referee delayed and denied MCO payments to Illinois’ providers.

“If it doesn’t work out, then that provider should go after the MCO,” Gumble testified.

At least two frontline Illinois medical providers have filed civil lawsuits to compel the state-contracted MCOs to pay their bills on time, in full and with transparency.

In one pending federal appellate court case, Saint Anthony Hospital in Chicago alleges the MCO payment shortfalls pushed the 123-year-old West Side safety-net facility to the brink of closure last year. Because of MCO billing denials, Saint Anthony said in court pleadings, its cash on hand fell from $20 million in 2015 — enough to fund 72 days of operation — to $500,000 in 2019, which was sufficient to keep the hospital open less than two days.

Eagleson told the BGA that she asked Saint Anthony for details about its unresolved bills, but “they have still not disclosed that information through depositions and through this whole lawsuit. So I mean, we can’t help solve what we can’t understand.”

In his court deposition for the Saint Anthony lawsuit, former state Medicaid Director Douglas Elwell testified the MCOs assured him they were denying only 10 percent of claims, while providers said it was more like 25 percent.

“We thought this ($46 million billing clearinghouse) would give us greater visibility into which number was accurate,” Elwell testified. “There were a whole lot of moving pieces. And nobody seemed to have the total answer, nor could we get to the total answer.”

In her deposition in the Saint Anthony lawsuit, Gumble said she did not know how many providers had, like Mercyhealth, cut contracts with MCOs and effectively dropped out of Medicaid because of billing problems.

“I have no idea,” she said. “The only time we had them would be if a hospital system was terminating with an MCO, and then we have, you know, what’s the issue, blah, blah, blah. And then, you know, and hopefully they work it out with — between the MCO and the provider.”

Gumble testified that Eagleson and her top aides called practitioners’ billing complaints “provider noise.”

Problems emerge, but fixes are slow

When Illinois’ antiquated fee-for-service MMIS system proved incompatible with the MCOs’ billing codes and procedures, the state allowed each MCO to set up its own format, leading to more billing errors and denials, records show.

“Obviously, the providers were complaining that it was very difficult to figure out what everyone was doing, and it wasn’t a transparent process,” Elwell said in his August 2020 deposition for the Saint Anthony lawsuit.

Some MCOs adjusted their billing procedures to accommodate Illinois doctors, but not the largest one, a subsidiary of the Centene Corp., Gumble said in her Saint Anthony deposition.

“There’s one plan that holds out because they have a hard time changing, because it’s a national plan. … They said we can’t.”

Rauner administration officials established a complaint portal in which providers could submit individual billing denials to the MCOs for reconsideration. “We really wanted to make the providers happy. Let them, you know, not have a lot of provider noise,” Gumble testified in her deposition.

But in his court deposition for the Saint Anthony lawsuit, HFS Medicaid manager Robert Mendonsa acknowledged that the complaint portal was overwhelmed by the deluge of disputed bills from 2018 through February 2020, and claims were getting lost instead of resolved.

“We did have a glitch in our provider complaint portal reporting,” Mendonsa said. “The database just got too big to report, unfortunately.”

Decatur’s community-based Heritage Behavioral Health Center said in a complaint ticket it was owed $57,000 in accounts receivable from one MCO dating to 2017. The center hired a third-party billing firm to handle this and other disputes. But after two years, the state’s complaint portal simply closed the ticket, according to letters the biller sent to the state.

Eagleson told the BGA the agency “revamped” the complaint portal last year. Tickets are no longer closed simply because they have been in the system too long.

Annual practitioner billing complaints to the portal dropped from an average of 3,400 in 2018 and 2019 to 1,200 last year, but the complaint numbers doubled during the first six months of this year, HFS records show.

As the complaint portal bogged down in 2019, Elwell instituted a series of twice-monthly meetings between leaders from the MCOs and providers.

But after Elwell left the agency in February 2020, Gumble testified, Mendonsa as his replacement told her to stop attending those Monday meetings.

“Robert basically said there is too many people sitting in this room,” Gumble testified. “When Robert took over, he said, ‘Don’t, don’t waste your time.’ So I didn’t. Because it’s too many people, like I said, sitting there all day.”

Mendonsa said in his deposition that the Monday meetings were pared back because they had proved effective, and there were fewer problems to resolve.

HFS officials told the BGA that more than $149 million changed hands as bills were resolved in those Monday meetings, most of it paid to providers by MCOs.

Some providers told the BGA they simply walked away from the meetings.

“It is a nightmare come to life that our industry is being asked to be on the front lines of the COVID-19 battlefield and yet continue to deal with the same denials, underpayments and administrative burdens,” Illinois State Ambulance Association President Christopher Vandenberg wrote in a letter to state lawmakers last year.

Citing the payment issues, the Illinois legislature in August passed a bill that would exempt some medical drivers from Medicaid managed care and return that industry sector to a traditional fee-for-services model.

Pritzker vetoed that bill, saying the exemption would disrupt care, but lawmakers overrode Pritzker’s veto in September.

Eagleson said the medical transport companies are being paid more than ever under privatized care. “We take their complaints very seriously and always have,” Eagleson said.

Eagleson and her top aides blamed prior state administrations for failing to heed provider complaints, creating a culture of distrust between providers, the MCOs and the state agency.

“When I first took this job, I heard from countless people — providers, trade associations, even the plans themselves: Thank goodness you’re here, and you’re giving us people to talk to and you’re trying to solve problems,” Eagleson told the BGA. “I hate to talk badly about predecessors, but I don’t know what all was going on to address some of this stuff.”

Kira Leadholm was assigned to the BGA as a graduate student from Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications.

This story was produced by the Better Government Association, a nonprofit news organization based in Chicago.