Did the story of Chicago begin in the south suburbs?

By Irv Leavitt for Chronicle Media — March 27, 2019

Patrick McBriarty standing on a flat-topped hill in Olympia Fields where he thinks Pere Marquette stood in 1674. (Photo by Irv Leavitt photo)

A handful of people say that a very significant incident in early Chicago history didn’t actually take place in Chicago, but in what is now a little suburb 30 miles southwest of the Loop.

“The people of Olympia Fields should be thrilled to be living next to a Mecca of Illinois history, an important part of the origin story of Chicago, and it’s hiding there in plain sight,” said Christopher Lynch.

Lynch and fellow Chicago resident Patrick McBriarty call themselves the “Windy City Historians.” They’ll release their first podcast March 29, about the theories of John Swenson, an amateur historian himself. Swenson, of Glenview, says his 35 years of research point directly at the Olympia Fields’ sparsely-visited Spirit Trail Park.

It’s the place he maintains 17th century French explorer Father Jacques Marquette made a historic campsite, and associated the word Chicago — or Chicagou or Chicagoua, depending on your preference — with what would become the Midwest’s biggest city.

The podcasters maintain that history books will be changed, and every Illinois school kid will know the name Olympia Fields.

That would be a shock to the 5,000 residents of a town where nothing much interesting happens. The village’s website includes a page recommending 11 “Things to Do,” and 10 of them are in other municipalities.

The more crime-prone towns surrounding Olympia Fields frequently generate bits of newsworthy mayhem now and again. But the little town itself is so quiet that the drivers of those TV trucks with the big antennas on top probably don’t even know how to get there without GPS.

Olympia Fields deserves more attention than it gets, Village President Sterling Burke said. It’s one of the wealthiest and most-educated majority African-American towns in America, he notes. Over 70 percent of the town is African-American, and over 98 percent of those residents own their homes.

It is not one of those Chicago suburbs where you will likely find a famous person living next door, unless he or she is retired. R. Kelly lived there, but he moved.

Personal finance website GoBankingRates considers it one of America’s 10 best suburbs to retire in. That must be right, because Olympia Fields residents are generally pretty darn old. In a state where the median age is 38, Olympia Fields’ median age is 53.

But nobody there is old enough to know for sure if Swenson is right about what did or did not happen in their territory.

Swenson, a retired management consultant, disagrees with the generally accepted understanding of the 17th century accounts of Marquette and his partner Louis Jolliet, and the French traders and explorers who came before and after them, traveling by canoe and portage with Native American guides across modern day Chicago.

Their route is said to be from Lake Michigan, across the sandbar at the mouth of the Chicago River, and then to the South Branch of the Chicago River, then the West Fork of the South Branch, and then a portage of up to seven miles, depending on conditions, to the Des Plaines River, and on to the Illinois River from there.

Swenson instead believes in a route to the south, from the Calumet River to the Little Calumet, then Butterfield Creek, Hickory Creek, the Des Plaines and then on from there. Two portages are involved.

Swenson’s version seems more arduous, but he maintains that no Native Americans lived along the “northerly route,” which he said ran through a grassy wasteland, with food hard to come by. But along his route, “there were Indians living all along, and you could buy food from them. There was more game, anything from wrens to buffalo.”

Marquette and Jolliet came through in 1673, and Marquette returned the following year without Jolliet to proselytize the native population to the west. Along the way, during a camping stop, Marquette and his party, he wrote, were faced with a flash flood.

“He gives a number equal to a 12-foot increase in water level, and there’s no way you could get a 12-foot increase, because it’s all flat” on the traditionally accepted route, explained McBriarty.

“It would just flow over the land,” Swenson said.

He said that meant it had to be a different route. He decided that it was one that passed a place where the sudden rise of water could take place — in present-day Spirit Trail Park.

The banks of Butterfield Creek were high enough to flood that deep and overrun the shore, forcing the party, as Swenson said Marquette wrote in his journal, to climb upon a nearby “butte.”

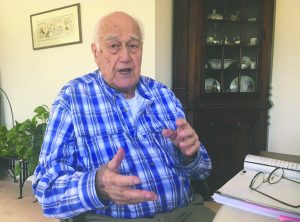

John Swenson says he has a theory that could put early Illinois history on its head. I could prove it in court, the former lawyer said. (Photo by Irv Leavitt photo)

There is something that looks like a butte there still, but Swenson is sure it’s more than that. He hired astronomer David Johnson to survey the flat-topped hill just off Olympia Way. Johnson found that the ends of the oval hill point directly at the sun as it rises in the winter and summer solstices.

It also lines up, on the winter solstice, with the Pleiades star cluster.

“All three events are very important to Native Americans and have been documented at sites throughout the United States as well as the western hemisphere,” Johnson wrote in his report.

That means, Swenson said, that the earthen structure is a place of worship, a temple mound. And wouldn’t it be reasonable, he said, for the Native Americans to build it along a canoe route leading to one of its largest habitations, which Marquette was then bound for?

McBriarty said neighbors of the park told him it’s still home to the garlic or onion-like ramps the natives and French called Chicagoua, for which Chicago seems to have been named, and which Marquette remarked upon at the site of his camp. There’s long been some mild controversy over which kind of stinky plants the old journals were talking about, with Swenson voting for garlic.

“The mayor of Olympia Fields is really the mayor of Chicagoua,” enthused Lynch.

Burke doesn’t seem to have that kind of ambition. “I’m not a politician,” he said. “I’m just a retired business guy.”

But he’s intrigued by the possibilities for his town.

“It’s an interesting theory,” he said “I’m always interested in any publicity or notoriety that would kind of promote our community.

“This could be a destination.”

Rich Gross, another local historian who has studied Illinois’ French explorers, said of Swenson, “He’s a nice guy. He’s just wrong.”

He said he reads the French explorers’ journals completely differently, and maintains that nothing should be changed. He adds that there were forests along the accepted route, where game was available, and there were plenty of places along the Des Plaines River where the flood drama Marquette described could have taken place.

“If there was a better portage to the south of the Chicago River, that’s where Chicago would be today,” he said.

Gross, McBriarty and other people have sent me many 17th-century maps that they maintain will prove their points about the portage routes, but I’m not including any of them. Some of them look convincing, and some of them look like they were drawn with a pencil clutched in a monkey’s fist.

Swenson’s podcasted story, which goes beyond the Jolliet and Marquette saga, will be covered in two parts, the second coming April 26. The first part is mostly about explorers who predated Jolliet and Marquette, McBriarty said.

McBriarty is the author of “Chicago River Bridges,” said to be the definitive book on the subject. He serves on the board that oversees the McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum, which oversees one of the smallest museums in Chicago, housed in the southwest end of the DuSable Bridge at Michigan Avenue.

His expertise comes in handy. Some of the other members of the board, including me, don’t know much more about what goes on in the bridge house than that’s where you can go to pay $6 to see the honking big machinery that makes the bridge go up and down.

Lynch has written a couple of books about Midway Airport, one a history, and one a book crammed with pictures taken in the days when all the big shot out-of-towners had to come through there if they were taking an airplane.

Those days were simpler than ours, and probably simpler than Jolliet’s and Marquette’s, too.

“History is full of different perspectives. It depends on what side of the fence one is on,” Burke said.

“Short of coming up with a time machine, no one may ever really know what the story is.”