‘Greater Chinatown’ grows as concerns over gentrification loom

By Igor Studenkov For Chronicle Media — July 27, 2017

Reach High Educational Center is one of the many Bridgeport businesses that caters to Chinese-Americans. (Photo by Igor Studenkov/for Chronicle Media)

Chicago’s Chinatown has been around for 105 years, but the Chinese-American community has grown beyond it for quite some time.

Since the 1980s, the community has been expanding to the neighborhoods to the south and east as first-generation immigrants and Chicago-born Chinese-Americans have been moving to Bridgeport, McKinney Park, Armour Square, South Loop and Brighton Park in increasing numbers. Much of it had to do with geographic constraints created by railroad tracks and highways limiting growth within Chinatown. If the 2010 census is any indication, the trend is only accelerating.

At the same time, Chinatown finds itself facing new challenges. Cultural clashes have emerged between newer immigrants and the older population. As the nearby South Loop and Pilsen neighborhoods face gentrification, there have been growing concerns that new development will drive up real estate values, and the community that has endured for over a century will face displacement.

According to the Chicago History Museum’s Encyclopedia of Chicago, the city’s first Chinatown emerged in 1880s on the south end of the Loop, near the intersection of Clark and Van Buren streets. By the first decade of the 20th century combination of rising rents, growing development discrimination and conflicts between the two major community associations led many Chinese residents to relocate into what was then a Sicilian neighborhood around Wentworth Avenue and what is now known as Cermak Road. Over the next few years the Chinese-American section of the neighborhood grew and expanded, though only to a point. Since 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act severely restricted immigration. But after it was repealed in 1943, the city’s Chinese population climbed, nearly doubling during the 1950s.

At the same time, Chinatown was being boxed in. Rail yard and railroad tracks formed barriers to the north, south and east, and the construction of Stevenson Expressway in 1964 created a southern border.

The creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 led to another wave of migration. Cantonese-speaking farmers and working-class immigrants tended to settle in Chinatown, while the Mandarin-speaking middle-class immigrants were more likely to settle elsewhere.

In 1970s, another enclave emerged as Hip Sing Family Association moved its headwaters to the other Side, around Argyle Red Line ‘L’ station. The group hoped to make it a “New Chinatown,” but the area soon became a settlement site for Vietnam War refugees. While some of them were ethnic Chinese, Vietnmese, Cambodian and Laotian refugees settled there as well. While the neighborhood still has some Chinese businesses, Vietnamese and other ethnic groups currently have a bigger presence.

In the late 1980s, a group of Chinese-American businessmen bought up the rail yard that formed Chinatown’s northern border. Over the next two decades, it was turned into Chinatown Square retail area, several small blocks worth of residential buildings and the Ping Tom Memorial Park.

At the same time, the Chinese-American population began settling in neighborhoods outside Chinatown, moving south of Stevenson Expressway and west along Archer Avenue. Like the Polish and Mexican immigrants before them, they settled in Bridgeport, McKinley Park and Brighton Park. Some settled further east, in the gentrifying Near South Side community area.

The 2010 census shows a growing Asian-American population in Chinatown and the surrounding neighborhoods. Armour Square, which includes Chinatown and the eponymous neighborhood further south, has 9,721 Asian-American residents, which accounts for 70 percent of its overall population. By comparison, it had 7,324 Asian-Americans in 2000, which accounted for 50.9 percent of the overall population.

Bridgeport’s Dalcamo Funeral Home’s sign is written both in English and Chinese. (Photo by Igor Studenkov/for Chronicle Media)

Near South Side is home to 3,307 residents who identified as Asian-Americans — a dramatic increase compared to mere 517 that lived there in 2000. Bridgeport has 11,038 — up from 8,851 in 2000 — which accounts for 35.8 percent of the population. McKinley Park has 2,445 — nearly double the 1,228 it had in 2000 — accounting for 15.7 percent of the population. Brighton Park has 2,252 — up from 1,326 in 2000 — accounting for nearly 5 percent of the population.

The Chinatown-based Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community has been describing this area as “Greater Chinatown.” Debbie Liu, the group’s community development coordinator, said that aside from these neighborhoods, there is a growing Chinese-American population in Canaryville, a neighborhood south of Bridgeport. According to the 2010 census, New City — the community area that includes Canaryville and the Back of the Yards — is home to 727 Asian-American residents. While the number is small, it represents a sizable increase compared to 175 Asian-Americans that lived there in 2000.

Liu explained that the major reason for the outward spread was a simple question of space. Even with the rail-yard redevelopment freeing up land, Chinatown remains constrained.

“Housing costs is a big driver for Chinese-Americans moving west to Brighton Park,” she said. “Chinatown core is very dense and its development is limited by physical barriers and the existing housing is most senior-oriented housing. There is more land west and the houses are bigger.”

China Wok, one of the several Chinese restaurants in McKinley Park. (Photo by Igor Studenkov/for Chronicle Media)

There is also the matter of convenience.

“Most people work in the city and these neighborhoods are still close to downtown and next to interstate entrances,” Liu said.

She said that while many families are moving from Chinatown out south and west, there are also cases of empty-nesters moving from the suburbs to Greater Chinatown neighborhoods.

Like other ethnic neighborhoods, Chinatown still serves as a port of entry for newly arrived immigrants. Liu said that while many move further out, most wound up staying in Chinatown, or somewhere nearby.

“Most people do stay, though, for the sense of community and the fact that you can get in-language services, native groceries and comfort foods at local restaurants,” she said. “The need is there and so families have started living in areas just outside of Chinatown core – the Greater Chinatown.”

Liu said that it is common for second and third generation Chinese-Americans to live in Greater Chinatown neighborhoods.

The growing presence of Chinese-American community is most noticeable in Armour Square, which is home to a number of Chinese grocery stores, restaurants, medical offices and other businesses. A number of Chinese restaurants in Bridgeport is growing, and the neighborhood is home to the Chicago Shaolin Temple and the Ling Shen Ching Tze Buddhist Temple. A few Chinese-American restaurants and businesses, such as Feng Auto Sales, can be found in McKinley Park as well. And many buildings in those neighborhoods have buildings that belong to Landmark Property, a Bridgeport-based Chinese-American real estate company, and many for-sale/for rent signs have brokers with Chinese names.

When asked whether Chinese-Americans faced any challenges or cultural tensions when they moved west, Liu said that the experience was mixed.

“As these communities are traditionally non-Asian, Chinese families have often counted on each other for a sense of community within their neighborhood,” she said. “Discrimination undoubtedly happens across the Greater Chinatown area as well as appreciation for others’ culture and identity.”

Liu added that Internet helped to create a sense of community in a way that would’ve have been possible 20 years ago.

“[There is] a community online on social media platforms like WeChat that helps people feel belonging even if their immediate neighbor may not look or talk like themselves,” she said.

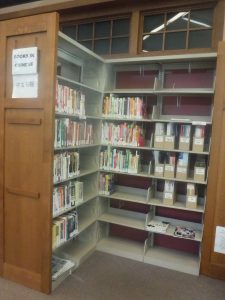

As a sign of McKinley Park’s changing population, the McKinley Park branch library has two stacks worth of books, magazines and newspapers in Chinese languages. (Photo by Igor Studenkov/for Chronicle Media)

Meanwhile, Chinatown itself is going through changes of its own.

First, there is the matter of newer residents.

“The older residents are older in age and had come from Southern China or Hong Kong speaking Toishan or Cantonese and reading Traditional Chinese [writing system], whereas the newer residents are younger in age and are coming from [mainland Chinese] cities speaking Mandarin, typically reading Simplified Chinese,” Liu said. “The newer residents tend to be wealthier and more educated. Culturally, these populations are very different and it’s been a conundrum for city services and restaurants to staff the appropriate dialects and to write menus, signs, and newspapers in Simplified or Traditional Chinese.”

The businesses have been changing to affect the population. For example, while Chinatown restaurants traditionally catered to Cantonese-speaking regions, the recent years saw a growing number of restaurants that specialize in cooking from northern regions and other areas.

There is also the looming concern about gentrification and displacement. Over the past 20 years, South Loop and the rest of the Near South Side has seen increases in real estate values. In 2016, the long-vacant 62-acre vacant land that stretches between Roosevelt Road, Chicago River, Rock Island District Line railroad tracks and the northern edge of Chinatown was acquired in a joint venture between Related Midwest and General Mediterranean Holding real estate firms. In spring of 2017, Chicago Tribune reported that plans included 10 million square feet worth of residential and commercial spaces.

Liu said that, on the long term, that is a concern.

“Although Chinatown is not undergoing gentrification at the moment, there are certainly threats given that our neighbors in Pilsen, South Loop, McCormick Place, and Bronzeville are all changing,” she said. “Additionally, the empty 62 acres north of the Ping Tom Park’s field house is prime real estate for development and will have serious impacts on Chinatown and potentially raising the costs of housing and amenities. Lastly, there are proposals to redevelop the last of the existing lands in the already-dense Chinatown area, which will have ramifications for the commercial and residential areas.”

The concerns were especially significant given Chicago Chinatown’s age.

“All Chinatowns in North America have succumbed to gentrification — except Chicago,” she said. “Other cities have seen new “Chinatowns” appear in other neighborhoods but we’ve stayed put for over 100 years.”

In April 2017, Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community and Loyola University released the Chinatown Anti-Displacement Community Research Project Report. In the introduction, it explained that Chinatown’s value as a tourist attraction, as well as its proximity to Chinatown and access to public transportation led to concerns about gentrification and displacement of the community. The study found that many residents, especially adults and seniors, were concerned about housing affordability, as well as the quality of public education, especially high schools. There was also perception that residents who wanted better quality of life would have to move to the suburbs instead of trying to improve the community itself. There were also perceptions that residents should have more civic and political engagement. The key to counter displacement, the report argued, was for residents, businesses and community organizations to work together to create a shared vision of the neighborhood, and ensure that any development that comes to Chinatown fits that vision.

“In the last decade, [CBCAC] has fought for the development of public resources, such as the Chinatown library, field house, boat house, park, and public transportation improvements,” the report stated.

“This history of advocacy demonstrates that the Chinese American community values civic engagement and willingness in shaping a shared vision for the Greater Chinatown area. Chinatown’s existing community and advocacy values are perhaps the greatest communication asset in the area. Local government, private developers, and new residents that have interests in the Greater Chinatown area would be served well to connect with Chinatown’s assets when thinking about future development and residential settlement.”

Liu said that, whatever happens, greater community involvement was key.

“Of course, gentrification and displacements are concerns, but it’s important for the community to take ownership of their own communities, so there’s a vested interest in improving it for themselves and their neighbors,” she said.

Read the current issue of the Cook County Chronicle

Free subscription to the digital edition of the Cook County Chronicle

— ‘Greater Chinatown’ grows as concerns over gentrification loom —