Leavitt: The truth will set us free, if we can only figure out what it is

September 9, 2019

J.K. Rowling’s kids’ book series was indeed credited with expanding youthful interest in reading, and the grown-up Potter fans may be part of the reason adult novels still flourish to some extent as newspapers perish.

Twenty years ago, I invited myself to a new Chicago suburban Islamic elementary school, and my concerns about whether this parochial school would prepare students for secular life were allayed in the first classroom I visited.

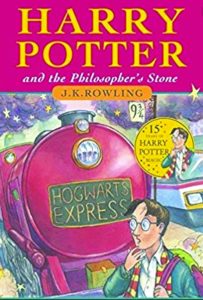

On every desk was a brand-new copy of “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.”

I asked the teacher whether this novel of spells and incantations squared with the Holy Quran.

“It is a wonderful book,” she said, peering at me as if I had crawled from beneath a rock. “It is making reading enjoyable for children all over the world. The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, allows our students to read fiction.”

J.K. Rowling’s kids’ book series was indeed credited with expanding youthful interest in reading, and the grown-up Potter fans may be part of the reason adult novels still flourish to some extent as newspapers perish. So I was a little surprised recently to learn that a Nashville priest had pulled the Potter books from a Catholic school library’s shelves.

“These books present magic as both good and evil, which is not true, but in fact a clever deception. The curses and spells used in the books are actual curses and spells; which when read by a human being risk conjuring evil spirits into the presence of the person reading the text,” the Rev. Dan Reehil wrote in an email to parents, according to reporter Holly Meyer of The Tennessean.

She wrote that Reehil assured parents that he consulted exorcists before making his decision. Meyer checked with an archdiocesan schools big shot, who backed the priest up.

Her story has circled the globe, making Americans look, even to people who have never been here, like the rubes we often are.

Another American religion story is simultaneously getting a lot of play. McKrae Game, the founder of Hope for Wholeness, one of the nation’s most well-known faith-based organizations dedicated to converting gay people to heterosexuality, admitted that he had caused unnecessary pain to innumerable people, including driving some toward suicide. And, by the way, he was gay the entire time, he said in an interview with Michael Majchrowicz of the Charleston, South Carolina, Post & Courier.

In the days following Game’s statements, I didn’t see Hope for Wholeness and other similar organizations indulging in any obvious public soul-searching. Instead, there was a scramble to see who could best claim their own anti-gay process as most effective, and steal away chunks of the now-embattled Spartanburg, South Carolina, organization’s market segment.

Meanwhile, the United Methodist Church continues to show significant cracking over leadership’s decision to shun gay clerics, while much of the membership wants to welcome them. The Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod reported this spring that it has lost over 22,000 baptized members in five years, part of a decline that dates to 1989. I doubt it’s a coincidence that the numbers started to drop when the nation began embracing equal rights for gay people. The synod didn’t change, but retained its official insistence that homosexuality is a sin.

So did the Missouri Synod, which is toying with a program of opening preschools, in an attempt to get families into churches, and slow down similar congregational shrinkage.

I haven’t taken a poll, but I’m betting that the majority of Catholic theologians do not think spells and curses are real, and I know for sure that a considerable number of Protestant experts don’t think that the testaments, old and new, call for making gay people second-class citizens.

And yet, these things are happening. I think it has as much to do with nations as denominations. In the United States, we tend to cherish the blame game, and look for scapegoats for all kinds of things.

For instance, lots of people say that video games make kids violent. Food stamps make people lazy. Mental illness leads to murder.

Statistically, none of these beliefs are even close to being true. Yet they are widely held, because of a simple reason.

If it’s someone else’s fault, it’s not ours.

The result is that we feel better about ourselves without doing anything about the things that need doing.

In the past, perhaps, bad problems’ causes, and solutions, were more obvious. Cholera and other diarrheal diseases were caused by contaminated water, so we fixed that, with sewers and water treatment. Lung cancer was being caused by air pollution and smoking, so we reduced factory and vehicle emissions, and came down on the tobacco business.

But the air pollution that remains is on the way to ending life on earth as we know it. Proliferation of weapons is leading to the deaths of many innocents. Processed food is causing cancer and other diseases.

American corporations spend energetically to convince us that all these problems have nothing to do with them. And as we have grown accustomed to accepting what should be obviously lame explanations — because they’re pounded home by massive amounts of advertising and lobbying — we have also learned to accept excuses, it seems, that are offered less expensively by those we want to believe, like pastors and aldermen, parents and physicians, athletes and entertainers.

There’s an old saying that it’s easier to tell the truth, because you don’t have to remember anything. But some people who know how to lie just keep on repeating their raps until it sounds reasonable. People who are actually telling the truth are not so organized, so they sometimes sound, comparatively, like the real liars.

Maybe, in an era when people can’t seem to decide who’s lying and who’s not, we might all decide, instead, to think for ourselves with a little off-grid learning.

We could start by spending more time in libraries, as long as the librarians are the ones deciding what goes on the shelves and racks.