‘Mollie’s War’ a women’s journey of service in World War II

By Holly Eitenmiller For Chronicle Media — March 22, 2018

For a brief time, Mollie Weinstein was assigned to a battalion in Normandy, shortly after the D-Day invasions of 1944. From left; Goldie “Johnnie” Johnson, Maria “Bats” Matistello, and Mollie. (Photo courtesy of Cyndee Schaffer)

Somewhere in England. Somewhere in France. When Mollie Weinstein wrote home during World War II her letters, mostly lighthearted narratives of dating and sightseeing, usually arrived in Detroit from “somewhere.”

Censorship by the War Office concealed the truth. As a medical intelligence stenographer for the Women’s Army Corps, Weinstein was rarely allowed to reveal her whereabouts or circumstances; details of her job, the umbrella of secrecy before D-Day, the constant bombing of England by Germany afterward.

“Here I am, back at work, with a most pleasant feeling of having had one of the most enjoyable experiences of my army career. You must admit, England certainly is fascinating,” she wrote from London, three days after D-Day. The Germans began bombing the city one week later.

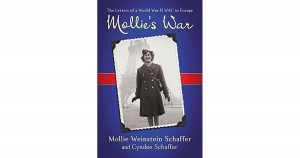

Weinstein’s two-year assignment is detailed in “Mollie’s War – The Letters of a World War II WAC in Europe”, a compilation of hundreds of letters, accompanied by historical facts that reveal the underlying reality of serving in wartime Europe.

“My mother was just an an ordinary citizen who felt it was her patriotic duty to serve her country,” Mollie’s daughter, Cyndee Schaffer told a group of listeners at Pekin Public Library during a March 13 program, “The Journey to Mollie’s War: the Women’s Army Corp and World War II.”

While serving in the military, Mollie wrote home extensively, particularly to her sister Beckie, ultimately accumulating more than 350 letters, as well as newspaper clippings and well-documented photos of friends she met and places she visited.

Feeling that the WAC veteran was on “borrowed time,” Schaffer began the tedious process compiling her mother’s letters and photographs in 2008, when Mollie was 91. She passed away in April 2012 at age 95, after the book was published.

“My mother always wanted to write a book about her experiences. It just took 65 years,” Schaffer said. “It became a family project and I spent a lot of time visiting the Pritzker Military Museum and Library in Chicago becoming familiar with the content and to put a proper perspective on the events that were occurring.”

“My mother always wanted to write a book about her experiences. It just took 65 years,” Schaffer said. “It became a family project and I spent a lot of time visiting the Pritzker Military Museum and Library in Chicago becoming familiar with the content and to put a proper perspective on the events that were occurring.”

The letters begin Oct. 20, 1943 when Mollie, 27, was stationed at Daytona Beach, Fla. for basic training, at a time when women were finally afforded full military benefits. Before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, women mostly served as volunteers with no official statuses.

“Because so many men were going to war, it became apparent that women’s participation in the war effort was essential,” Schaffer said, quoting the WAC’s first director Olvetta Culp Hobb, “Women who stepped up were measured as citizens of the nation, not as women … this was a people’s war, and everyone was in it.”

In December 1943, Mollie left Florida for training in Wilmington, Calif. then was sent to Ft. Oglethorpe, Ga. two months later, the overseas staging area for WACs. Mollie was able to visit home once before she left, but was not allowed to mention where she was going or what her role would be overseas.

Key persons to her story during that time were a handful of fellow WACs Mollie met, such as Dottie Dix, Maria Batistello, Goldie Johnson, and her closest friend of all, Mary Grace Loddo, who passed away in 2009.

“Many of the WACs found a special camaraderie, and she forged closed friendships and bonds through the pressures and demands of war, together with the knowledge that they were serving their country,” Schaffer said.

Molly traveled to London by way of the ship SS Lle de France April 1944. English rationing was strict. In place of milk, Mollie was given calcium tablets and rare were fruits and sweets. A peach, she wrote in July 1944, cost about $1.50, which converts to $20 in 2018.

Cyndee Schaffer began the process of compiling her mother’s war time letters and photographs in 2008. Mollie Weinstein Schaffer passed away in April 2012 at age 95, after the book was published.

After June 6, 1944, D-Day, Mollie began divulging in her letters a few details of the war, and the German’s onslaught of V-1 flying bombs in London. “If you promise not to say anything to Mom and Pop, I will reveal a few interesting items … there is a real war going on, Beck, I see it every day,” she wrote in a correspondence dated July 26, 1944.

Mollie continues, detailing a night of bombing when she awoke after a bunk mate lay next to her in fear and placed Mollie’s helmet on in her sleep. “You can bet your boots both of us felt to see if we were wearing our dog tags,” she wrote.

Her duties continued through August, when she was transferred to the muddy trenches of Normandy, where she and her fellow WACs bunked like men and bathed from cold water-filled helmets.

France followed in September, where she remained for a year, employing her ability to speak conversational French, which she learned in high school. She was transferred to post-war Germany in August 1945, her final assignment before going home.

“Stenographers and typists were essential in the European theater, and she was with the department that reviewed the extensive records that the Nazis left, claiming that their experiments were done to enhance medical research,” Schaffer said. “They found that this was not true.”

Douglas Schwartz, Cyndee Schaffer’s husband, presents Mollie’s Weinstein’s Detroit arm band from her days with the Women’s Army Corps during a program at Pekin Public Library March 13. WAC enlistees were given armbands representing the state from which they enlisted, with Mollie’s being Michigan. (Photo by Holly Eitenmiller / for Chronicle Media)

In the early morning hours of Nov. 9, 1945, Mollie awoke aboard the Queen Mary to view the Statue of Liberty and the lights of New York City. Shortly thereafter, she met and married Army Capt. Jack Schaffer and they moved to Chicago.

In her two year journey, along with serving the United States, Mollie visited many thrilling and exotic locations, enjoyed innocent dates with a number of servicemen, and learned much about European culture and cuisine, according to her daughter.

“Her story documents the human side of life during the war, a life that alternates between fear and romance, exhaustion and leisure,” Schaffer said. “It is impossible to know what your parents were like before they became parents … reading my mother’s words and seeing photos of my mother as a young, carefree woman who made decisions for herself and traveled the world made me realize the full life that she had before she became a wife and mom.”

Schaffer is a technical writer from Northbrook, who hosts frequent speaking engagements to bring about awareness of the importance of women in the military. For more information on “Mollie’s War” and for a calendar of events, visit www.mollieswar.com.

—- ‘Mollie’s War’ a women’s journey of service in World War II —-