Morton Grove serviceman finally gets honored for heroism in WWII

By George Castle For Chronicle Media — November 7, 2017

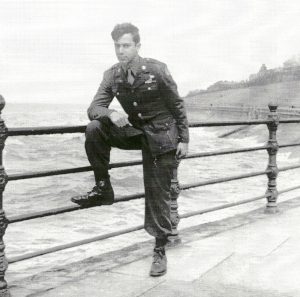

Herman Sitrick stands beside a WWII photo of himself at the Legion d’Honneur ceremony. (Photo by Russ Fling)

Honors long delayed are still honors richly deserved.

So when 50-year Morton Grove resident Herman Sitrick, 92, stepped out onto the ice at the United Center Oct. 5 as the armed forces veteran typically honored during the National Anthem, he collected yet another due bill that first should have been paid in 1945.

Blackhawks public address announcer Gene Honda did not elaborate beyond Sitrick’s name. But he no doubt would have drawn gasps from the nearly 22,000 present if he had described Sitrick’s heroism during the Battle of the Bulge: as a half-frozen GI cradling an eight-shot M-1 rifle, he captured 21 Germans single-handedly.

While battlefield chaos reigned in all directions and SS troops committed their worst atrocities of the war against American POWs, Sitrick obeyed all the laws to which he had been sworn. He was the latter-day version of Sergeant York, the American hero portrayed by Gary Cooper in a memorable 1941 movie, who had single-handedly killed or captured many dozens of Germans in World War I.

Sitrick already had one prisoner he had snared by himself, a sergeant who had no more fight left in him. When told by his commander to get help for his company blocked by the Germans, he took the POW on a hike, finding a half-bombed farmhouse for temporary shelter. He stashed the sergeant inside, then astoundingly saw other Germans by the ones and twos also seeking refuge in the house. Sitrick disarmed each one of them.

“I had a gun on them and they hadn’t expected me,” he said. “There were see-through steps I was sitting behind. I took their arms and put them back in the corner. I’m not surprised since they were regular German troops. If someone has a gun on you, you surrender. By the morning, I had 21 prisoners.

Herman Sitrick (second from left) being honored before the Blackhawks season opener Oct. 5 (Photo courtesy of Chicago Blackhawks).

“If they were SS troops, fanatics, I probably wouldn’t be here.”

The next day, Sitrick got his POWs taken off his hands when he flagged down a tank, part of Gen. George Patton’s Third Army quickly arriving for the relief of the besieged troops in the Battle of the Bulge.

An Army snafu prevented Sitrick from getting at least the Silver Star in the wake of his startling act of cool composure under blizzard-like conditions. And after hearing of his feat, reporters from national magazines descended on Sitrick’s company to interview the greatest American hero. But Sitrick already was at the rear, being treated for frostbitten feet. The story did not get told.

Had Sitrick been available in his eternally modest manner to chat about his heroism, he likely would have been pulled from the line via orders from the highest authority in Washington, D.C. to go on a stateside war bonds propaganda tour or such.

Leaving his unit previously had not been Sitrick’s first choice. Prior to his collecting of POWs, he had been wounded in action four times in France. Such frequency qualified him from being exempt from further combat duty. But an officer told Sitrick American units were short of experienced men. So he voluntarily returned to action.

Then and now, Sitrick never preferred to talk about his actions. He had two good reasons.

When mustered out in 1946, he simply wanted to get on with life with wife Marcia and raise and support a family of three sons via numerous broadcast sales and management positions, and a Skokie-based advertising agency he still runs 27 years into Social Security age.

More poignantly, Sitrick likely suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, then labeled “combat fatigue.” He talked about his wartime experiences to his family only in drips and drabs.

“I had nightmares in which I’d be shouting (to other soldiers) to take cover,” Sitrick said of his early months of marriage. “When I woke in the morning, Marcia told me of these nightmares. I had no recollection of ever having them. I didn’t remember any of it. I broke out in beads of sweat, according to my wife. She said she had to hold me down at times.”

Just like awards for his feats, there is no statute of limitations on PTSD. When Sitrick suddenly began getting recognized in the past few months for his service, the flashbacks returned even after seven-plus decades. His family consoled him with the thought he was stepping forth, reluctantly, to help honor his GI comrades who never made it home.

Sitrick never sought any honors. To co-workers and bosses, like now-Blackhawks president John McDonough, Sitrick mentioned nothing. They were shocked and surprised when suddenly, after the long-delayed word of his heroism was finally spread by representatives of veterans groups, he was awarded the Legion d’Honneur, the highest honor given by France to a foreigner for military and civil actions. Sitrick was feted in a River North ceremony staged by the French Consulate.

Herman Sitrick throws out the first pitch at Wrigley Field with Marcia Sitrick by his side. (Photo courtesy of the Sitrick family)

In the wake of the French honor, Crane Kenney, the Cubs’ president of business operations, was informed of Sitrick’s story. Sitrick had served under then-marketing chief McDonough for more than 25 years, starting in 1983, as the Cubs’ media ad buyer. Within a day of the contact with Kenney, Sitrick was invited to be honored pre-game at Wrigley Field. He picked Sept. 10, but had to take a rain check due to a short illness. Hopefully he’ll take his bows sometime early in the 2018 season.

As the team’s top executive, McDonough ensured the Blackhawks would not miss saluting Sitrick. He was the first veteran honored this season, taking his place next to a retired Air Force lieutenant general and Anthem singer Jim Cornelison. Sitrick’s family members worked hard to ensure after his illness he’d be healthy enough to attend the ceremony.

Sitrick’s sons, their wives, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren — many whom had traveled from Los Angeles and Phoenix — crowded into a United Center suite to watch the ceremony. And in the second period, McDonough himself stopped in to pay an emotional tribute to his longtime adman. McDonough had first contracted with Sitrick with the old Chicago Sting soccer team in 1981 before bringing him over to Wrigley Field two years later.

With a voice cracking at times, McDonough said a personal highlight was his long relationship with Sitrick.

“I’ve been around three teams that have won Stanley Cups, we’ve sold out the United Center nine years in a row, (but) nothing will ever top my experience and the time I’ve spent with Herman Sitrick,” he said. “I’ve missed him a great deal. There’s nobody who has a larger impact and more profound impact on my life than Herman.

“I think this is a great lesson for all of you who get too busy in your life, that don’t take the time to call somebody you love, who has done so much to help you in your life, this has made my life tonight, Herman.”

Seconds later, McDonough did his best to sum up Sitrick the modest man.

“I was not (previously) aware of his bravery and his heroism and all he accomplished,” he said. “He is consistent. He doesn’t talk about himself. He likes to talk about other people. But I’m not surprised. It’s dignity, it’s humility, class and everything I’ve learned from him.”

Sitrick the adman was true to his chief promoter’s pitch.

“The hardest part at my age was getting down to the ice and going back up,” he said. “I did feel honored I was being singled out that way.

“I never felt I was the center of attention until this happened. It was a first for me.”

The Blackhawks honor soon turned somewhat bittersweet. A few days after the United Center ceremony, Marcia Sitrick passed away surrounded by the family that had assembled to honor her husband. The couple were married 71 years.

The Sitricks seem to have been granted long lives for a reason: Herman to bear witness to personal morality under fire, and Marcia to bolster him through those unwelcome flashbacks. Herman Sitrick continues as best as possible with one more honor way overdue: from the U.S. Army itself.

And even with Marcia’s passing, the multiple honors and family reunion emphasized life in new ways. In the United Center suite came forth a story about son David Sitrick’s wife, Los Angeles attorney Miriam Goslins Sitrick. She is the daughter of Holocaust survivors, Herman and Hetti Goslins, who hid from the Nazis for years behind false walls in a righteous protector’s home in a small Dutch city. Unlike the celebrated Anne Frank, also attempting to similarly hide, the Goslins survived the war — all the while with local Nazi headquarters right across the street.

Decades later, Herman Sitrick and Herman Goslins, united by marriage of their children, quietly traded survival stories accomplished several hundred miles apart. In their meeting of peace, both were right where they were supposed to be.

Free subscription to the digital edition of the Cook County Chronicle

Read the current issue of the Cook County Chronicle

— Morton Grove serviceman finally gets honored for heroism in WWII —-