New book takes a look at the hey-hey days of Wrigley Field vendors

By George Castle For Chronicle Media — July 10, 2018Such a sweet deal — Lloyd Rutzky made a mint selling frosty malts at Wrigley Field.

Keeping detailed, down-to-the-penny financial records that would have made the late Yosh Kawano, the legendary Cubs’ clubhouse chief proud, Rutzky shows he cleared $87.90 peddling the popular chocolate treat on June 29, 1969.

Some 41,060 fans, with at least 10,000 more turned away at the gate, packed the ballpark for Billy Williams Day as the first-place Cubs swept the archrival St. Louis Cardinals in a doubleheader. The mob needed their 25-cent sugar fix early as Fergie Jenkins outdueled Bob Gibson 3-1 in a tense “lid-lifter.”

Rutzky’s haul was impressive by any income-earning standards of the day. He probably made more money on that Sunday than Cubs center fielder Don Young earned that day with a minimum baseball salary of $12,000. For another comparison, a Chicago corporation counsel made $6,300 annually.

“On June 28, a single game against the Cardinals, I made $45.80,” Rutzky said. “At that time, $30 was considered a real good day.”

Meanwhile, on his own frosty malt vending rounds in that memorable ‘69 season, Joel Levin sometimes found himself stationary at some far end of the upper deck, his triple load of goodies placed on the ground. He did not have to make a move or utter a special vendor’s sales pitch. Fans mobbed him on the spot to buy the malts.

“You could sell out of product by early in the game,” Rutzky said. “Sometimes they’d reorder and the Borden’s truck would show up during the game. The vendors would load up their cases straight from the truck.”

If Rutzky’s and Levin’s recollections sound like a kind of golden age for ballpark vendors, well, it was.

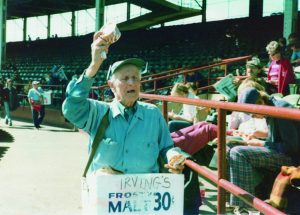

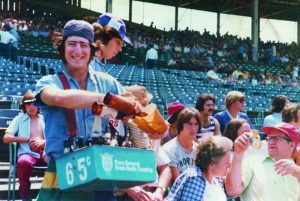

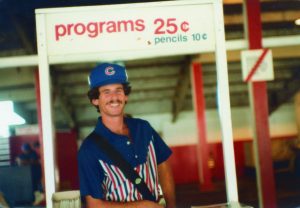

Photo of Lloyd Rutzky, selling 65-cent beer in the mid-1970s. He now sells it for $10. (Photo courtesy of Arcadia Publishing)

“The late 1960s were magical times for vendors,” Levin said. “Everyone’s going to make money. Everyone’s going to go home happy.”

With 22,000 unreserved grandstand and bleacher seats on sale the day of games, a land-rush of fans engulfed Wrigley Field for many dates to snare their perches in first-come, first-served fashion. They hoped to see four future Hall of Famers — Jenkins, Ernie Banks, Billy Williams and Ron Santo — win the team’s first pennant in 24 years.

The Cubs had to open the gates as early as 9 a.m. to alleviate the crush of lines at the gates. The day-of-game seats sometimes were filled by 11 a.m. with standing-room tickets then going on sale. Ken Holtzman, who tossed the first of his two Cubs no-hitters on Aug. 19, 1969, recalled how more than 10,000 already were seated and making noise for the pitchers’ batting practice session, the first workout of the day.

That time, place and people are recalled by Rutzky and Levin in their new book, “Wrigley Field’s Amazing Vendors,” part of the “Images of Modern America” series put out this month by Arcadia Publishing of Charleston, S.C.

The remembrances of Rutzky and Levin would not have been enough, though, to put out the book. Rutzky developed a photography hobby while at Columbia College. Around 1970, he began turning his camera on his fellow vendors to record their routines and personalities. At first, the vendors were puzzled or even reluctant to stop for a second to pose. Years later, they eagerly asked Rutzky for copies of the photos.

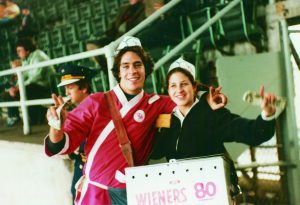

Vendors Howard Kadet (left) and Melinda Korer, one of the pioneer female vendors. Korer was nicknamed “Tweety Bird.” (Photo courtesy of Arcadia Publishing)

As the 2000s progressed, Levin — retired from vending in the mid-1970s — and Rutzky both thought of writing books on the vendors. Further inspiration came when Levin also noticed a familiar face on page 65 of Arcadia’s 2004 book, “Forgotten Chicago.” The image was of the famed Irving Newer, an almost-toothless, nearly-blind vendor peddling peanuts at old Comiskey Park. Almost any fan who frequented Wrigley Field and old Comiskey Park in the latter part of the 20th century either bought goodies or saw Newer.

Levin is a longtime Peterson Park resident on Chicago’s North Side. Rutzky grew up in South Shore before moving to Glenview in 1969. Now he resides in Bartlett. But both their emotional groundings were at the ballparks. They collaborated on the photo-heavy book which freezes time from the late 1960s through the early 1980s.

They dedicated “Wrigley Field’s Amazing Vendors” to Newer and “all employees who toil anonymously under the stands and in the aisles of major-league ballparks.”

Through Rutzky’s photos and several others donated by other vendors, they show the 1969-vintage, pale blue and almost military-style fatigues of the vendors. The getups jazzed up with red-white-and-blue-striped smocks as 1970s fashion got more garish. A number of photos even show a short-lived, 1980-vintage red robe uniform.

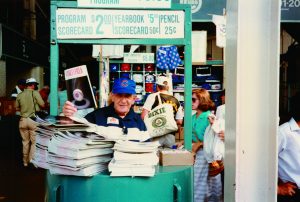

Martin “Marty Mo” Moshinsky selling programs at the first night game at Wrigley Field on Aug. 8, 1988. (Photo courtesy of Arcadia Publishing)

Also shown were Andy Frain ushers and Pinkerton security personnel, along with the women who worked in the “dry room” commissary where hot dogs were wrapped for sale. Age-old stalwarts Newell and Martin Moshisky are shown on their rounds, with “Marty Mo” displayed selling $5 souvenir programs at the first Wrigley Field night game on Aug. 8, 1988. The night-game shot is apparently the most recent of the collection published.

Some prominent folks got their start as vendors, a classic way to raise money for college tuition or supplement a full-time income. A photo of striped-garbed John W. Rogers, Jr. from August 1978 was published. Rogers went on to become founder and CEO of Ariel Investments LLC. A then-and-now contrast was featured with a photo of Rogers, Jenkins, Banks, Williams and Cubs chairman Tom Ricketts meeting Barack and Michelle Obama at the White House in 2013, when Banks received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“The experience of being a vendor was transformative for me,” Rogers said. “It was a job I looked forward to every single day because it combined my love of sports, my desire to stay physically active, and my motivation to be an entrepreneur.”

“Wrigley Field’s Amazing Vendors” works best, though, as a time-trip to another, more casual, personal and inexpensive era at the ballpark. The vendors and other ballpark personnel sitting in different grandstand sections is an absolute gateway to a more pastoral — if more losing — Cubs past. The photos are also a gateway into a Chicago where it was not “what you know, but who you know.” Many vendors got jobs through friends who recommended them to the parent Service Employees International Union local.

The culture and cost for vendors has absolutely changed. A typical sellout crowd at Wrigley Field in 1969 consumed some 60,000 soft drinks at 15 and 25 cents apiece, 40,000 bottles of beer at 45 cents each and 50,000 hot dogs at 30 cents each. Now Rutzky sells beer at $10 apiece.

The huge increase is not only due to the massive hike in salaries — Ron Santo was best-paid Cub at around $90,000 in 1969 — but also the required markup for the concessionaire. As an example, an inquiry to Miller Park’s SportsService in 2005 about selling a $26.95 Cubs book at the Milwaukee stadium when the Cubs fans swarmed to town revealed the sale price would have to be rocketed to $48 to handle the markup.

Ballparks now open their gates no earlier than two hours before first pitch. With the vast majority of seats sold well in advance, fans often do not show up until near gametime — and often into the first and second innings. The vendor thus has far less time to push his product. Far more expensive seats also could cut into discretionary income for buying food on an impulse basis from a vendor.

Beer man Lyle Cohen temporarily shifted to selling scorecards. (Photo courtesy of Arcadia Publishing)

In the mid-20th century, fans did not have the array of eating and drinking choices around the ballpark. Not even a McDonald’s or Taco Bell existed. Wrigley Field has also dramatically expanded its concession stands. In 1969, a fan sitting in the upper deck had to buy food when he first started ascending the steep ramps without a big stand upstairs. At a 1971 doubleheader packing more than 43,000 into the ballpark, a fan sitting down the right field line in the upper deck had to settle for a cold, soggy Italian beef sandwich due to other vendors being sold out well before they reached his location.

Eventually, Levin did not miss carrying his load up the ramps on a hot day. Interestingly, he started vending in 1962, when the Cubs often closed the upper deck due to small crowds for a 103-loss season. The first game he vended was the 1962 All-Star Game, the second of two the major leagues played annually at the time. He became a Chicago Public School teacher, but never forgot his fellow vendors. Levin served as a pallbearer at Moshinsky’s 2008 funeral, then showed up at the grave nine years later to remind “Marty Mo” the Cubs had finally won a World Series.

“We had camaraderie and cutthroat (tactics),” Rutzky said. “That was kind of part of the fun — trying to beat your friends, outsell them.”

Get your free subscription of the Cook County e-edition

—- New book takes a look at the hey-hey days of Wrigley Field vendors —-