The Elon Musk tunnels could change everything

By Irv Leavitt for Chronicle Media — June 27, 2018

Artist’s conception of Chicago Express Loop “electric skate” vehicle. (Photo courtesy of The Boring Company)

As a limousine crawled along in a soul-crushing Kennedy Expressway traffic jam, Loop-bound from O’Hare, a U.S. Olympic Committee official sat in the back, talking about what he was experiencing.

“This is what will kill them. This is the one reason for sure that they can’t do it,” he said, referring to Chicago’s then-current bid for the 2016 Olympics. “They can probably solve everything else. This problem is too big.”

It turned out he was right. Or, maybe, Chicago just lost out due to an insufficiency in the quality of bribes to the International Olympic Committee, which eventually awarded the games to Rio de Janeiro, not exactly a paragon of efficient infrastructure, either.

But the point is inescapable. The ride from O’Hare to the Loop colors the beginning of a trip to Chicago for many tourists and business people, and that hue is usually not a soft, comforting pink. The Kennedy trip — which can, amazingly, be both tedious and terrifying at the same time — is also the last memory most visitors take away with them, to tell their buds back in Kansas or Saskatchewan.

The trip to O’Hare does not get better as other things burgeon, including the capacity of the airport and the number of shiny buildings still rising to ridiculous heights downtown.

Chicago is growing as a headquarters town, but that’s mostly driven by companies moving in from the suburbs, seeking proximity to cheaper and younger employees who want to live in the city. Companies arriving from outside Illinois could be making more of an impact, bringing new tax revenue that could foster state government solvency. But most out-of-state CEOs seem to like most everything about Chicago except the fun they have getting there.

The trip to O’Hare is holding Chicago back. Midway Airport, at a quarter of the capacity, can’t help much more than it does, let alone the lame, counter-productive attempts to off-load volume to Milwaukee and Gary. That’s why Elon Musk is the hero Chicago needs, right now. If he’s up to it.

If he can really bore two holes through the Illinois clay to carry 125-mph people-hauling electric skates that cover the trip in 12 minutes, and on his own dime, he not only fixes a problem. “The Chicago Express Loop” suddenly makes Chicago a better tourist destination (as if Michigan Avenue’s current cargo shorts crowd wasn’t annoying enough), and gives it a shot at becoming the most attractive convention and headquarters city in the United States.

Business travel is still important. It’s not all GoToMeeting.

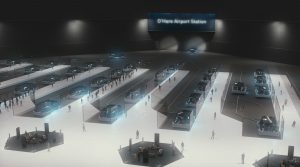

Artist’s conception of Elon Musk’s Chicago Express Loop service’s O’Hare station. (Photo courtesy of The Boring Company)

Musk’s concept, at first blush, seems like literally remaking the wheel. Why not, for instance, just convert the O’Hare branch of the CTA’s Blue Line to an express train, so that it cuts out the “dwell time” at all those local stations? That way it’d take a lot less than the current 45 minutes to train it from the Loop to O’Hare, right? Done!

It would, maybe, trim five minutes. Probably less. And conversion of the entire branch to high-speed or express is just not in the cards. The Blue Line is too important the way it is. At 86,400 riders a day, it’s the second-busiest line in the system.

And it’s getting busier. Half of the top 10 fastest-growing stations in the whole system are on the Blue Line between the Loop and O’Hare.

There isn’t enough track space to run both expresses and locals, and it almost doesn’t matter. For business and tourist airport travel, an el train is just not very attractive. Everybody knew that before the CTA stretched the line out to O’Hare in 1984. But they did it anyway.

Musk’s concept is so game-changing because a 12-minute trip effectively reels O’Hare in from the edge of Cook County to somewhere around Halsted and Madison. As far as time is concerned — and what else matters much, nowadays? — Chicago would have the busiest downtown airport in the world.

“If you look at the history of Chicago,” Rahm Emanuel told the Tribune, “every time we’ve been an innovator in transportation, we have seized the future.”

If all goes reasonably well, he is right. The future, however, in some of those cases, quickly plunged chunks of the economy into the past that were otherwise unprepared to be consigned to history.

One example: The Illinois Tunnel Company, which in 1903 started building almost 60 miles of tunnels under downtown Chicago. The tunnels bored big holes in the commerce of freight handling and teamster employment, stealing jobs in businesses ranging from coal hauling to transporting newsprint to Tribune Tower.

Musk’s The Boring Company will drill much more deeply into the local taxi, limo and shared-ride businesses. He promises that he will be significantly under-pricing them, and giving riders a higher-quality product, so what else could happen?

The jobs that disappear down his tunnels aren’t easily replaceable. These already-challenged trades are still among the very few ways that under-educated people can make a decent living, and that part-timers can use to supplement income with a degree of freedom.

The taxicab business has survived a lot of blows, some self-inflicted. But this punch — taking what amounts to three-quarters of the Loop-O’Hare trade out of the market — is different. Don’t expect to have the kind of access to quick pickups anywhere in or near Chicago that you enjoy now, imagining that cars will be freed up from the O’Hare routine. There’s a limit to the willingness of people to stay in a business that’s unprofitable.

Taxing of the Musk trips is assumed, and that’s good for the local government and economy. But most of the O’Hare run money now goes to drivers, who spend almost all of it quickly and locally. You can reasonably expect most of the money that Musk earns from driverless airport vehicles to stick to him and his investors.

The tunnels sound like science fiction, but that’s what Musk does. He is, after all, the Tesla electric car and SpaceX rocket-ship guy. When he says he has a better way to dig tunnels, and he can do it cheaper and faster than others, he has space cred.

Maybe he can do it as well as he says. Maybe not. But tunneling is not as big a deal as many people who have seen “The Great Escape” may think it is. It’s not like that.

There are long, sturdy old tunnels all over Chicago, dug for various purposes. The Illinois Tunnel guys got 59 miles done downtown, complete with track and switching, in four years. This was in a period when most horsepower came from real horses.

Two men were killed in construction. After a flood in a tunnel that was being built to serve the Union Stock Yards, somebody turned off the compressed air that forced out the methane gas that naturally seeps from Illinois clay. A supervisor named Michael Barry went in to check the flood extent, and asphyxiated. His brother Patrick went in after him, and he died, too.

This helped put an end to the Stockyards branch. But a couple of deaths may not be enough to stop a modern project.

In 1999, Jason Briggs, 26, was crushed by a rail car at an excavation jobsite 270 feet below 106th Street on Chicago’s southeast side. He was the 14th person killed in the construction of the 109 miles of huge underground conduits of the Deep Tunnel flood-control project.

Everybody took a three-day weekend, then got right back to work.

Get your free subscription of the Cook County e-edition

— The Elon Musk tunnels could change everything —-