War doesn’t sidetrack Ukrainian ballet dancers

By Kevin Beese Staff Writer — February 27, 2024

Olekandr Stoianov and Kateryna Kukhar perform the ballet “Giselle.” The couple will bring their Grand Kyiv Ballet to the Harris Theater for Music and Dance in Chicago for a performance of Giselle at 7 p.m. Wednesday, March 7. (Ksenia Orlova photo)

Sharing bomb-shelter space with audience members and band members has become commonplace for Ukrainian ballerina Kateryna Kukhar.

“We will start a performance and 20 minutes into it, the air alarms will go off and we will all have to go into the bomb shelter,” Kukhar said. “This is real life. This is how our people live every day.”

Kukhar, who also instructs youths in ballet, noted that despite her students being distracted and often displaced, having to take shelter because of Russian planes’ bombing runs in the ongoing war with Ukraine, her students have still been able to achieve. She noted students came away with a silver and bronze medal in a recent international competition in Berlin.

“Our children know about what is happening,” Kukhar said.

Kukhar and her husband, Olekandr Stoianov, will bring their Grand Kyiv Ballet to the Harris Theater for Music and Dance in Chicago for a performance of the ballet “Giselle” at 7 p.m. Wednesday, March 6.

Kateryna Kukhar (Ksenia Orlova photo)

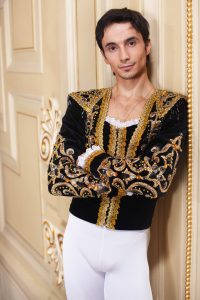

Olekandr Stoianov (Ksenia Orlova photo)

The couple and their two children have relocated to Seattle due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Getting reunited with their children was an effort that neither parent will soon forget.

On Feb. 24, 2022, Stoianov was with the ballet company’s production of “Giselle” in France. Kukhar was with ballet students in Germany.

“I got a call from our baby-sitter who was with our daughter,” Kukhar said. “She was alone with our daughter in the car and they were crying. I watched on TV as our airport was attacked and firebombed.

“I felt like I was in hell. I couldn’t breathe. I was in shock. I couldn’t believe what they had done. Nobody could believe what was happening to our country. We had to try to get our children.”

Stoianov asked a friend to take the baby-sitter and their daughter to the Poland border as Kukhar made her way to France to join her husband.

“It would be eight to 10 hours normally,” Stoinanov said of the trip from their home to the Poland border. “In eight hours, they had only gone 70 miles” because of all the traffic.

Adding to the parents’ worries was the fact that the friend’s car broke down and their daughter, the baby-sitter and the friend all had to spend the night in a random building.

“It was the best day of our lives when we were back with our children,” Stoinanov said.

Their son was in a separate Ukrainian city with his godfather and his family. The couple had to get their son at the Hungary border. Because of traffic, their son and his godfather had to leave the car they were traveling in and walk eight hours to the border.

When reunited as a family, Kukhar wept with joy for her family and then in sorrow for her country.

“My son asked, ‘Mother, why are you crying? The war will stop, we will go back. My friends are waiting for me,’” Kukhar said.

If sports would have worked out for either Stoinanov or Kukhar, they might never have found their calling in ballet.

At age 9, Kukhar was at a playground with her grandmother when a teacher with the national gymnastics team invited Kukhar to join the group.

In a flexibility test at team practice, the coach pushed one of Kukhar’s legs to the floor with her hip extended.

“I was a little shocked. I felt pain,” Kukhar said. “I had tears coming down from my eyes. I didn’t say anything, but I went home and told my mother I didn’t want to do gymnastics anymore. The next day I went to a ballet group that was in the same building.”

Stoinanov remembers his older brother kicking him every day. His parents put them both in boxing. Every time it was time to spar, he got put with his older brother.

“I told my parents I didn’t want to be a fighter,” Stoinanov said. “I would sit at home and watch TV. One day, I saw the ballroom dance championships. I liked the dresses, the good hair. I told my mom I wanted to be a ballroom dancer.”

After some success, a retired dancer told Stoinanov’s parents that they should consider ballet for him and recommended they send him to Kyiv — 1,000 kilometers from their home.

“I said I wanted to stay with my friends,” Stoinanov said. “They said they would give me a bike if I went.”

Both Kukhar and Stoinanov said they are excited about the upcoming performance in the Chicago area, which has the second largest Ukrainian population in the United States, with more than 54,000 residents. Most of those residents live in Chicago’s Ukrainian Village neighborhood, where the Ukrainian National Museum is located.

“I can’t wait to come to Chicago. There are a lot of Ukrainian-American people there,” Stoinanov said. “We will give them a piece of our heart. We want to show people that Ukraine is not just about war. It has beauty and culture.”

Kukhar said a ballet performance can be like a religious experience.

“Going to the theater is like going to church. You come with your troubles and problems, and for one or two hours you live another life,” she said. “Your spirit is purified; your soul gets air; and you go home with answers.”

For tickets, call 312-334-7777 between noon and 5 p.m. weekdays or go to

https://my.harristheaterchicago.org/10441/10442?_gl=1*ubw0zm*_gcl_au*MzExMjAwNzIwLjE3MDg3NDAyMTY

kbeese@chronicleillinois.com