WGN’s 72 seasons of baseball broadcasts fading to black

By George Castle For Chronicle Media — September 20, 2019

Ad for a 1960-vintage early road color telecast. The Reds and WLWT actually beat WGN by one year (1959) in putting on home games in color. (Photo courtesy of George Castle)

“Childhood’s End” traditionally was known as title for a 1953 Arthur C. Clarke science fiction novel.

But near the end of Sept. 2019, it more aptly applies to the conclusion of 72 seasons of baseball telecasts on WGN.

The final Cubs game airs from St. Louis on Sept. 27. The concluding signoff will come at the end of a White Sox-Tigers game at Guaranteed Rate Field on Sept. 28. Appropriately, Steve Stone, who has logged 31 seasons in the booth — second to Peoria native Jack Brickhouse’s 34 years — will man the broadcast in his typical erudite analyst style.

The fade to black after Stone’s last words will cut the cultural umbilical cord to Happy Days-type remembrances for multiple generations who grew up with WGN’s telecasts. Things may not necessarily have been better overall in life, but baseball was surely more accessible and affordable in various WGN incarnations of televising the Cubs and Sox.

All that was required from the outset in 1948 was a paid-up electric bill to turn on the TV and switch the dial to “Good Ol’ Channel 9” within signal range of its Chicago transmitter. Later, after the addition of color, instant replays, the uplink to a satellite and Harry Caray, a modest monthly contribution — compared to today’s inflated payouts — to the cable company brought daily baseball entertainment all over the United States.

Devotion to the telecasts usually whetted the fan’s appetite for attendance at the ballpark, for as little as $1 for Wrigley Field bleachers in the hallowed season of 1969. Kids as young as early teens could simply wake up that morning and decide to attend a game with just $5 in their pockets, and usually return home with change left over.

Nothing is forever, so baseball and WGN could not go on ad infinitum.

After all, WGN itself, started in radio form by Col. Robert R. McCormick and his Tribune Co. in 1924, no longer has a Chicago-based owner, having just been sold to Dallas-based Nextstar. The Sox air on WGN Radio, which from 1958 to 2014 was the staple home of the Cubs. Meanwhile, the Cubs now air on AM-670,which was often the Sox radio outlet from the 1960s until two decades into a new century via the old WMAQ and more recently WSCR/The Score sports-talk station.

Plus, WGN’s primacy as the Chicago baseball video outlet has steadily eroded since 1998, when the first chunk of Cubs telecasts were farmed out to the then-Fox Sports Chicago.

Ostensibly, WGN desired to air network entertainment programs in place of some primetime baseball. In mock outrage, Caray protested he did not want to play second fiddle to “Buffy The Vampire Slayer.” He never lived long enough, though, to migrate over to cable with grandson Chip Caray, the original plan for 1998.

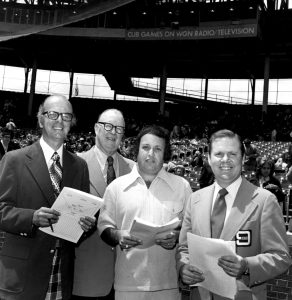

An early 1970s photo of (from left) WGN sports editor Jack Rosenberg, play-by-play man Jack Brickhouse, director Arne Harris and Brickhouse booth sidekick Jim West. (Photo courtesy of George Castle)

WGN’s carriage of the Cubs for all 72 seasons and the Sox for 51 has been commemorated even more recently partly thanks to numerous nostalgic celebrations this season of the ’69 Cubs. That was the team emblematic of the transformative effect on Chicago baseball team loyalties via exposure on WGN’s video bully pulpit in the late 1960s.

The increase of Cubs telecasts corresponding with the departure of the Sox for fledging UHF station WFLD-TV (now known as Fox-32) in 1968 turned the Sox into second-fiddle status in Chicago and the surrounding Midwest region. Then the transformation into a superstation cemented that pecking order that still exists today, even with the return of Sox games to WGN for their final 30-season run starting in 1990.

The Cubs and Sox shared WGN’s airwaves with telecasts of home games and a smattering of road contests for the first 20 seasons of coverage, starting in 1948. However, the Cubs still televised more games — the all-daytime home schedule — while the Sox blacked out night games to protect the gate.

Although Sox consistently contended in the American League and the Cubs were a drooping “second-division” National League franchise, the Cubs’ ratings were higher, according to the remembrance of Vince Lloyd, the late WGN play-by-play man who worked baseball on both TV and radio. Although Wrigley Field season attendances were embarrassingly small for the second-largest market, the fans were no further away than their TV sets.

Meanwhile, the Sox garnered higher TV-radio rights fees despite televising fewer games. Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley granted the broadcast rights for under-market value as a believer in broadcast exposure.

Wild about Harry. Harry Caray was in the Cubs’ booth from 1982-97. (Photo courtesy of Grant DePorter)

Financially troubled Sox owner Arthur C. Allyn enacted a penny-wise, pound-foolish decision to leave WGN, inking a $1 million annual rights deal with WFLD in the summer of 1966. Angered about the gentleman’s agreement between the two teams to share WGN, Wrigley gave his TV outlet permission to dramatically expand to 60 road games in 1968 without a corresponding big hike in rights fees.

Almost correspondingly in 1967, WGN had fulfilled a years-long request from the likes of WTVO in Rockford, WMBD in Peoria and WCIA in Champaign to provide a schedule of telecasts. The audience potential in what was for all practical purposes a three- or four-channel universe proved off the charts for a crucial July 24-26, 1967 series in St. Louis. The upstart Cubs, after not sniffing first place in midseason since 1945, had tied for Cardinals for the top the second time in July after winning the July 24 game.

For the first game, some 1.5 million viewers in the Chicago area tuned in with a 46 share (percentage of households watching TV at the time). About 100,000 more viewers in the originating market with an identical 46 share watched when WGN fed the Tuesday night, July 25, game to stations in Rockford, Peoria, Champaign, the Quad Cities, Milwaukee, Madison and Marion, Ind. The regional audience was gauged at an astounding 3.5 million. The Wednesday, July 26, game was picked up by all the stations except Madison and Marion.

Cubs fans were being won over in downstate Illinois that used to be Cardinals bastions. In the meantime, access to the Sox was crimped by the switch to a UHF station when less than 50 percent of Chicago viewers were as yet equipped to watch channels 14 and above. With the development of the Cubs into an exciting contender — “Cub Power” was the slogan of the time — and many households first purchasing color sets to watch Wrigley Field in the daytime, the Cubs enjoyed a perfect storm of exposure region-wide.

Brickhouse, aided starting in 1954 by WGN sports editor Jack Rosenberg, a Pekin native, gave the fans everywhere in the Midwest what they wanted with his homey, homerish play-by-play style. In addition to his trademark “Hey, Hey!” home-run call he accidentally discovered early on in his WGN tenure, Brickhouse had a slew of pet phrases for all occasions.

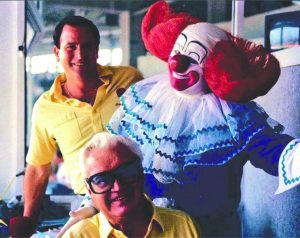

Bozo the Clown visits Steve Stone (left), Harry Caray in the booth. (Photo courtesy of Grant DePorter)

On a particularly dramatic home run, Brickhouse would yell, “Weeee …” after his “Hey, Hey!,” often adding, “Atta boy (player name)!” A dramatic play, good or bad, would elicit an “Oh, brother!”

When a Cubs pitcher zeroed in on a no-hitter, getting to two strikes with two outs in the ninth, or any similar dramatic situation, he’d set up with “Watch it … watch it now!” or “You can cut the tension with a knife!” Meanwhile, “A Pier 6 donnybrook” was a baseball brawl. An “Alphonse and Gaston Act’’ was a mix-up between outfielders.

A too-little, too-late rally came “after the horse was out of the barn” or “a day late and a dollar short.” A quick change of situation was “For a hot minute there.” A high-scoring, mistake-filled game would be “the married men vs. the single men at the company picnic.”

Caray picked up where Brickhouse left off when he succeeded him in the booth in 1982. He did not have as many pet phrases as Brickhouse beyond his own “Holy Cow!” home-run call. But the “Cub Fan, Bud Man” injected so much bravado and show-biz into the broadcasts, led by his seventh-inning singalong, that he lifted the superstation broadcasts to a new level of popularity. Caray soon became more popular than almost all the Cubs players.

And as Caray’s delivery actually declined due to health problems, Stone buttressed the broadcasts with his precognitive analysis and own sense of humor.

Compounding the 1968 error in switching to WFLD, new Sox owners Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn jumped the gun by switching games off free TV — WGN had reacquired the Sox for one season in 1981 — and starting a subscription SportsVision channel in 1982.

The “Sunshine Boys” were years ahead of the market, though, with Chicago and many suburbs not yet wired for cable. Baseball fans simply were not used to paying for their video pleasures. In addition, Caray jumped ship after 11 Sox seasons due to the projected decreased exposure — and he also did not like Reinsdorf. Another perfect storm boosted the Cubs even further ahead of the Sox.

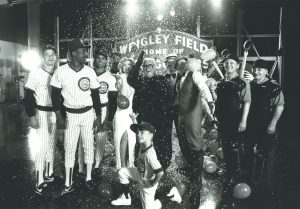

Harry Caray sings “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” during the seventh-inning stretch in 1987. (Photo courtesy of Grant DePorter)

The South Siders periodically would outdraw the Cubs, for a first-place finish or the 1991 opening of what is now called Guaranteed Rate Field. But the Cubs’ overall fan base, now reaching coast to coast via satellite, far outpaced the Sox even after the Sox put part of their schedule back on WGN in 1990. Hall of Famer Frank Thomas even branded Chicago a “Cubs town” in 1993, not pleasing Reinsdorf with the comment.

WGN-TV concocted almost a personalized style, featuring director Arne Harris’ “hat shots” and close-ups of any attractive woman wearing short-shorts and a tank or bikini top. That MO will long survive the divvying up of Cubs telecasts to the team’s new Marquee Network and the Sox to NBC Sports Chicago.

When the station’s history is written, it will be branded as the most influential TV outlet in the annals of the teams it covered. WGN will be gone from the Cubs and Sox, but its video imprint will far outlive it.