Centennial trek on Lincoln Highway marks nation’s first transcontinental auto route

By Jack McCarthy Chronicle Media — August 28, 2019

Mark Ounan talks about his 1918 Dodge military sedan last week during a stop at Cantigny Park in Wheaton as part of a 100th anniversary of a cross-country U.S. Army caravan that traveled the nation along the Lincoln Highway. (Photo by Jack McCarthy / Chronicle Media)

Like almost anything past its 100th birthday, Mark Ounan’s Dodge Bros. military staff car has its cranky moments.

But the olive-hued former military sedan continues to hold its own as it resumed a 3,000-mile journey to California after a two-day stop last week in Wheaton.

“We’re trying to drive it all the way,” Ounan said as he and members of the Military Vehicle Preservation Association took a break last week from their cross-country trek. “Little problems here and there, mostly because of the heat. We were in Pennsylvania and it was so hot — in the 90s every day — and climbing those hills on Route 30 is rough. Now it’s cooled off and rained for a couple of days. It was real nice.”

Ounan’s 1918 Dodge is the oldest vehicle in a group, traveling the former Lincoln Highway, tracing the cross-country route a U.S. Army convoy made in 1919 to test the ability to move troops and equipment long distances.

The original trek included 82 vehicles and nearly 300 personnel — including a young lieutenant-colonel named Dwight D. Eisenhower.

“They found out it was really, really hard,” Ounan said of the 62-day journey.

The convoy was plagued by poor roads, equipment failures and other unforeseen problems in the run from Washington D.C. to San Francisco. Eisenhower wrote in a report that from Illinois to California most of the journey was on dirt roads.

Participants were also aware of the trek’s historic nature.

“The expedition possessed an historical significance, it being the first motor convoy to cross the American continent,” wrote Army Capt. William C. Greany in an official post-convoy report that’s among documents in the Eisenhower Presidential Library. “(It was) comparable in its sphere to the first ox team prairie-schooner trek, the first steam railroad train, and the first airplane flight across the vast expanse of fertile valleys, rolling prairies, rugged mountains and desolate wilderness that lie between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.”

Owner Mark Ounan (right) and Cantigny official Ian Richardson talk about the 1918 Dodge military sedan that’s part of a cross-country journey commemorating the centennial of a U.S. Army trek across the continent. (Photo by Jack McCarthy / Chronicle Media)

The current MVPA caravan consists mostly of vehicles from the 1940s and more recent vintage, all owned by veterans and collectors. The approximately 50 restored vehicles are rolling at a leisurely pace on well-paved roads at around 35 mph, matching the maximum speed of Ounan’s Dodge.

They’ll also make frequent stops along the way for people to see the vehicles up close, like during last week’s break at Cantigny Park and the DuPage County Fairgrounds. The caravan is scheduled to arrive in California by Sept. 14.

The stop at Cantigny — the former home of the late Chicago Tribune publisher Col. Robert McCormick — was appropriate given his World War I era service and his estate’s focus on that conflict and a recently enhanced First Division Museum on the grounds.

STAR OF THE SHOW

Ounan’s meticulously restored Dodge Bros. stick shift vehicle with tan fabric roof has an indirect linkage to the 1919 tour. His Dodge did not make the trip, but five similar models did. None are known to have survived beyond the 1930s.

“I’ve seen the list of serial numbers of this and none of them exist anymore,” said Ounan, a Pennsylvania native and retired Army sergeant.

A plaque at Kishwaukee College in Malta notes the first concrete mile on the Lincoln Highway. (Photo by Jack McCarthy / Chronicle Media)

The Dodge was deemed surplus in the 1930s and acquired by an officer who eventually moved it to Salt Lake City. That’s where Ounan acquired it in 2007 and brought it back to Pennsylvania, put in work to get it running and took it on a 90th anniversary cross-county Lincoln Highway trek in 2009.

“This is the oldest one on the (current) trip,” he said. “This was a mid-level (officer’s vehicle), lieutenant colonel, maybe a major gets a Dodge. You know a general is going to ride in a Cadillac. … These are a little sturdier. They’re smaller, but they’re a little more robust.”

Ounan said if he were around in 1919 he’d jump at the chance to make the cross-country run.

“Oh yeah, I’d love to make this trip,” he said. “It would have been a huge adventure. But this is good. This is as close as we can get.”

THE REAL ‘MOTHER ROAD’

Motorists may still get their kicks on the legendary U.S. Route 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles, but there’s arguably no historic roadway with a greater impact than the Lincoln Highway.

Route 66 (1926-85) is immortalized in stories, songs, a TV show and even in “Cars,” the animated Pixar/Disney movie.

But the Lincoln Highway — a transcontinental collection of state, county and local routes stitched together across 13 states early in the 20th Century between Washington D.C. and San Francisco — may have the stronger claim as the nation’s Mother Road.

A commemorative marker in downtown Joliet notes the spot where the Lincoln Highway and U.S. Route 66 intersected. (Photo by Jack McCarthy / Chronicle Media)

It was also the nation’s first national monument to President Abraham Lincoln, predating the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. by six years. Lincoln’s image is featured in some original and replacement highway markers.

“The idea of the Lincoln Highway came from the fertile mind of Carl Fisher, the man also responsible for the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Miami Beach,” according to the Lincoln Highway Association (www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org). “With help from fellow industrialists Frank Seiberling and Henry Joy, an improved, hard-surfaced road was envisioned that would stretch almost 3,400 miles from coast to coast, New York to San Francisco, over the shortest practical route.

“The Lincoln Highway Association was created in 1913 to promote the road using private and corporate donations,” the Association’s account continued. “The idea was embraced by an enthusiastic public, and many other named roads across the country followed.”

Maps of the routes show starting points in New York with a spur route to and from Washington D.C. As it proceeded west, there were other spur routes from Detroit and Chicago to the main route.

Most of the route was eventually designated as U.S. Route 30. When the Interstate Highway system came into being, Interstate 80 replaced Route 30 as the nation’s main East-West roadway.

THE FIRST CROSSING

Six years after the Lincoln Highway route was created, the Army got involved with its cross-country trek.

According to the Lincoln Highway Association, the original 1913 national route runs broadly from New York City to San Francisco with several auxiliary and alternate routes.

In 1919, the U.S. Army organized its 82-vehicle expedition to survey the military’s mobility during wartime conditions. Eisenhower joined the convoy as an adviser and observer.

Part of the caravan of restored military vehicles participating in a cross-country caravan celebrating the 100th anniversary of a U.S. Army trek along the Lincoln Highway. (Photo by Jack McCarthy / Chronicle Media).

“I heard reports that he felt kind of trapped and bored with what he was doing,” Ounan said. “In World War I he ended up being in charge of a tank school in Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) … Right after the war he was just kind of sitting around and not doing anything. So he went to the brass and kind of weaseled his way onto the trip as an adviser.”

Eisenhower noted the caravan’s struggles — poor roads, bridges unable to handle heavy equipment and breakdowns.

“In those days, we were not sure it could be accomplished at all, nothing of the sort had ever been attempted,” wrote Eisenhower in “At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends.”

That convoy would have a lasting impact on the man who later served as European Supreme Allied Commander in World War II and U.S. President from 1953-61.

“After seeing the autobahns of modern Germany (after World War II) and knowing the asset those highways were to the Germans, I decided, as president, to put an emphasis on this kind of road building,” Eisenhower later wrote. “The old convoy had started me thinking about good, two-lane highways, but Germany had made me see the wisdom of broader ribbons across the land.”

EISENHOWER’S INTERSTATES

The result was today’s Interstate Highway System, arguably the greatest public works project in history.

“The obsolescence of the nation’s highways present(ed) an appalling problem of waste, danger and death,” Eisenhower said. A modern network of roads is “as necessary to defense as it is to our national economy and personal safety.”

Interstate highways now cover all 50 states — even Hawaii —and a total of 46,876 miles. The Federal Highway Administration estimated the cost of building the system at $128.9 billion, of which 90 percent was paid by the federal government.

Individual states are responsible for operating and maintaining interstates in their jurisdictions.

TRAVELING THROUGH ILLINOIS

In Illinois, the original route largely follows U.S. 30 or adjacent roads from the Indiana-Illinois state line to the Aurora area. From there it tracks north on Illinois Route 31 west of the Fox River to Geneva before heading west on Illinois Route 38 through DeKalb — where the official street name is the Lincoln Highway — and on to Rochelle and Dixon.

A crooked sign at the edge of cornfield in Creston directs traffic along the Lincoln Highway route. (Photo by Jack McCarthy / Chronicle Media)

The Route 38 leg will eventually rejoin U.S. 30 en route to the Quad Cities and the Mississippi River.

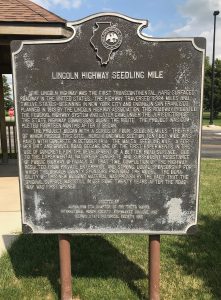

That original Illinois route also ran on modest rural roads like Heggs and Harvey Roads near Oswego and Keslinger Road in Kane County. In tiny Malta, a historic marker at Kishwaukee Community College commemorates the Lincoln Highway’s first “seedling” or paved mile, a project that demonstrated a permanent type of road construction.

There’s also a notable detour near at Franklin Grove and the national headquarters of the Lincoln Highway Association, which was set to host a lunch for caravan participants late last week.

A series of interpretative gazebos, murals and road markets line original Lincoln Highway route in Illinois.

The convoy’s stop at Cantigny allowed visitors a chance to check out equipment although a scheduled seven-hour open house was cut back due to rain. Cantigny donated fuel and meals for participants.

The caravan departed Wheaton Aug. 22 for an overnight stop in Iowa. It is scheduled to reach San Francisco by mid-September.