Chicago hacker space movement is growing

Jean Lotus — April 5, 2016

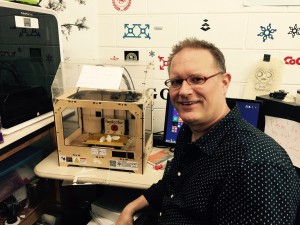

Pumping Station One Board Member Ray Doeksen demonstrates a Makerbot dual replicator 3D printer. (Photo by Jean Lotus/Chronicle Media)

Chicago has affixed its economic hopes onto the promises of entrepreneurial incubators, coding schools and startups — hoping for a quick tech buck.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel even introduced a city technology plan to boost the “21st Century economy.” But the Chicago startup world of exposed-brick workspaces, laptops and decaffeinated tea bars never seems to be — well, at all fun.

However, just under the radar of the city’s tech scene is a booming DIY creative and computer culture as unique as Chicago. The maker space/hacker space movement in Chicago and Cook County is taking off. People are gathering in co-owned spaces to share tools, cut steel, laser-etch glass, punch leather and program Raspberry pi units.

Chicago’s oldest hacker space, Pumping Station One in Avondale, celebrated its seventh anniversary April 2 with a seven-hour birthday party and open house.

Three-hundred-plus full members belong to the organization, which has a quarter-million-dollar operating budget and is run completely by volunteers. Subscriptions cost $70 a month for a full membership and $40 for a “starving hacker” membership.

Other hacker spaces have opened in Pilsen, at the Museum of Science and Industry and the Harold Washington Library. A suburban hacker space, Workshop 88, operates in Glenn Ellyn.

On the roof of Pumping Station One, a booth-shaped blue Dr. Who TARTIS perches above the 5,500-square-foot building at 3519 N. Elston Ave. The group’s name derives from the firehouse at the epicenter of the 1871 Chicago Fire.

The space is filled with worktables in use, scattered with transistors, resistors and motherboards. Drawers are stuffed with screws and bags of tiny LED lights. People wearing goggles melt metal threads with soldering irons and clamp wires with needle-nose pliers. Others etch glass with a laser cutter, or cut sheets of metal to make a folding toolbox. People socialize, tinker or use laptops to program a 3D printer. Some even brew beer by computer.

“It’s an ant farm with no queen. It’s 400 cats. People doing whatever they want and arguing about it,” said Ray Doeksen, director of public relations and a volunteer board member.

Dan Meyer, a former PS1 board member who now is the director of the Museum of Science and Industry Fab Lab has a different perspective.

“It’s actually a very tightly run organization and the board meets once a week,” he said.

The concept is a collective work and social space with tools either donated, refurbished or purchased with subscription money. Larger tools at the space include a vertical milling machine, band saws, a water jet and a $20,000 4-by- 8-foot Shopbot computer-controlled wood router.

“That’s a cool tool and nobody’s going to buy that for their own garage,” said Doeksen. “The only way you’ll be able to get it is by joining a space like this.

“After we have filled the space with ordinary tools, we’re going crazy. I want to get a robotic arm.”

What happens when someone breaks a saw blade? First, members are expected to ’fess up immediately if something breaks.

“Things break, that’s what happens,” Doeksen said. “Sometimes it happens if someone isn’t trained on the machine.”

Some members serve as “area hosts” and take care of replacing or ordering new parts. The group buys new tools and replacement parts from the $20,000 monthly budget.

The space has no actual employees, which helps with liability exposure.

“We have to get really good insurance,” Doeksen said. “And no one can be here under age 18 without a parent. These machines can be dangerous.”

Jason Shanfield mills a new router bit at Pumping Station One Hacker Space. (Photo by Jean Lotus/Chronicle Media)

Origins of Hacker spaces

According to hacker myth, the hacker space/maker space movement (the words are used interchangeably) began after the fall of the Berlin Wall. German hackers from East and West Berlin formed “C-Base” in 1995 to mesh computer coding with leftover Soviet hardware. Parties and live music were hallmarks of their “Burning Man for hackers” conferences.

Highland Park native Mitch Altman, then a programmer living in San Francisco, was inspired by the culture.

“When I was at the conference in Germany, it was so cool I didn’t want it to stop. So I decided to try to make a place where it never had to stop,” he said.

With friends, he co-founded Noisebridge in 2007 in an industrial building in the Mission District. The group was committed to open-source computer programming and keeping participation free.

Communication between hacker spaces helps different groups solve common problems such as paying rent, personality conflicts and writing grants. Noisebridge was briefly overwhelmed by problems with homeless people who crashed the space and allegedly pilfered tools and money.

The board closed Noisebridge and reopened with a more focused message and better crowd control. Last summer hundreds of librarians toured Noisebridge during the American Library Association conference in San Francisco.

In Chicago in 2009, when Pumping Station One started in a smaller space, also on Elston, the space contained a living loft where a tenant could stay to help with rent.

“It’s not a good idea to have people living here,” Doeksen said. “Now we don’t even have a couch to lie down on. We still have a shower and a kitchen though, for convenience.

“We learned a lot from Mitch’s experiences with Noisebridge. We’ve been able to confer with members of other spaces when we have had significant problems.”

Most problems stem from clashes of nerdy personalities, compounded by miscommunication through computer screens instead of face-to-face.

“We try to attack issues like that early and in person,” Doeksen said.

Far from competing, groups in Chicago’s “hacker eco system” support each other and turn to each other for help. A hacker summit, hosted by the Chicago Public Library last year keeps organizations in touch. Many people are members of more than one group.

“It can be a little incestuous,” Doeksen said.

In Pilsen at the South Side Hacker Space, Spokeswoman Jessica Fong said transparency in the not-for-profit organization has helped the board and 40 members who pay $35 or $60 a month.

“There’s definitely a feeling of sharing all of the tools and knowledge,” Fong said.

South Side Hacker Space is four years old and has moved into space at 37th Street and Morgan Avenue. One unique feature is “we’ve been given a lot of 3D printers that we’re getting on line.” Fong said.

“I can see why Chicago is a center for hacker spaces in the Midwest because we’ve had such a base of manufacturing here in our history.”

Manufacturing is undergoing terrific change, said Dan Meyer, who started as a metal-casting welder on the factory floor and spent 20 years in industrial manufacturing.

“We feel like we’re living in the future. It’s shocking to us that we’re teaching people like this,” he said. “Eventually everybody is going to know this, being able to use these tools and how empowering it is.”

The Mold-O-Rama machines made famous at the Museum of Science and Industry are a good way of looking at how hacker spaces are “democratizing manufacturing,” Meyer said.

“With the Mold-O-Rama you get a U505 plastic submarine, that someone else has designed for you. Now you can design anything yourself. In a few years, something like a spaceship can be designed in a hacker space,” he said.

The Museum of Science and Industry Fab Lab serves about 600 guests a month with a special ticket purchase, Meyer said. The lab is based on a model created by the Massachusetts Institute for Technology.

“The maker scene is now a source of skilled people to work in manufacturing careers, for which there’s lots of demand.”

Fong says SSMS wants the space to help the community. She’s sometimes frustrated that Chicago’s startup tech culture doesn’t acknowledge the importance of maker spaces.

“Unless we make big bucks, no one focuses on maker spaces as an investment in people and education in the community,” she said. “It would be nice to have backing and support from the mayor and politicians.”

Meanwhile, the movement is growing. A PS1 satellite space, Analytics Lounge at Cicero and Grand Avenues, is built around scientific uses for sonic absorption spectrometers and a scanning electron microscope that weren’t being used as much at PS1.

“It’s more a chemistry and science-oriented space,” Doeksen said.

“Three years ago I predicted, wrongly, that there would be hacker spaces everywhere,” he said. “Turns out there is a financial impediment until you get to a certain membership size.”

Pumping Station One will be expanding in a few months to 11,500 square feet.

“We’re doubling our space and I have to get 50 or 60 new members to stay where our discretionary budget is right now,” Doeksen said. “Ban the skepticism! Full speed ahead!”