Bee colony collapse impacts McHenry County

Adela Crandell Durkee — June 1, 2015

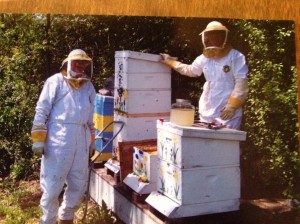

Tina Wildbrandt and her 83-year old father Allen Visin know first-hand how tenacious beekeeping can be.

One out of every three bites of food is directly or indirectly on our tables because of the honeybee.

A healthy hive is so important that the U.S. Postal Code allows for queens to be sent through the mail. Beekeepers, however, are seeing a decline in the honeybee population due to colony collapse disorder.

For more than 10 years, beekeepers lost one-third of their bees each year due to colony collapse disorder. Scientists are uncertain what causes colony collapse, but they do know some of the factors that contribute to the malady.

It’s a serious problem to beekeepers as well as farmers.

$15 billion in crops each year depend on honeybees. McHenry County produces $1.56 million per year in farm produce. Although the majority is in corn, wheat, and soybeans, farmers in McHenry County also grow vegetables and fruits, which rely heavily on honeybees.

McHenry County has 79 registered beekeepers.

Tina Wildbrandt and her 83-year old father Allen Visin know first-hand how tenacious beekeeping can be. Visin, wanted to be a beekeeper since he was 10 years old. Five years ago, he and Tina took a class at McHenry County College, studied like mad, networked with other beekeepers, and finally took the plunge. Wildbrandt and Visin are passionate about stemming the tide of colony collapse.

“It’s really physical work,” said Wildbrandt. “Each hive weighs about 80 pounds. But we love the bees. They’re so gentle. And all they want to do is work, work, work.”

Bees have a collective social behavior, and even a social healthcare. Bees weed out sick individuals and will even oust a queen, or swarm away from the hive or origin to create a new colony, if they sense the queen is weak.

Some experts blame Nature Deficit Disorder, which occurs when humans forget their connection with nature. After WWII, farming became more industrialized. The average farm size in McHenry County is 332 acres; 82 percent are family owned. In comparison, the size of an industrial farm can be 1,100 acres or more.

Farmers began to use pesticides and herbicides and chemical fertilizers. They stopped planting cover crops and clover to naturally replenish the soil. Farmers stopped planting flowering shrubs as hedgerows dividing the fields.

Farms became monocultures, or food deserts for bees, dominated by soybeans, wheat, and corn. Miles and miles of one crop create a banquet for pests. When farmers separate fields by a hedgerow, they create a natural barrier to the spread of disease, and provide a banquet for honeybees. To combat crop diseases, more pesticides got developed. Pesticides and herbicides make their way into bee populations. Many times a hive has six types of pesticides.

Neonicontinoids, a new class of pesticide, coats the seed, moves through the plant as it grows, and kills the pests. Non-lethal doses migrate to pollen and nectar. Neonicontinoids is a nicotine-like chemical and has a similar effect on bees as tobacco has on humans. The bees get a little buzzed. Some become disoriented, lose their way back to the hive, and die. Some bees return to the hive and lead others back the addicting nectar. Honeybee colonies can disappear almost overnight.

A mite called Varoa Destructo compromises the immune system of honeybees. These mites attach to a bee larva. Usually six mites attach to each bee.

Wildbrandt explains what happens in human terms, “It’s like having six parasites the size of your fist, sucking the energy out of you.”

The mites grow, living on the juices of the bee, weakening it, so it cannot mature to a strong bee. This impacts the overall health of the colony.

Bees keep the hive at a constant temperature 24/7, all year round, by beating their wings. Too many mite-infected bees can cause the hive to lose temperature control and collapse. Wildbrandt and Visin often lose one of six hives over the winter this way.

The more modern penchant for clean, manicured lawns contributes, too. Lawn application makes up 11 percent of the pesticide use. Yard after yard of clean, pristine lawns create a food desert, just as miles of corn or soybeans do.

Individuals can make a difference in bee health with minimal effort.

- Plant rooftop gardens and keep rooftop hives in housing complexes.

- Plant bee-friendly flowers. Wildbrandt explains that flowers with flat heads like catmint and Echinacea are ideal. She’s convinced her landscape architect husband, Doug, to allow dandelions to take over part of their back lawn.

- Plant flowering shrubs and flowers between fields and along roads or streets in hedgerows to provide a variety of nectar and pollen to bees.

- Avoid pesticides when possible.

- Search for native or indigenous flowering plants that require little chemical assistance to thrive.

- Consider cover crops as a way to replenish the soil and keep out weeds and pests, rather than chemicals.

- Plant a meadow in the back yards. If space is limited, plant a meadow in a pot on the patio.

We can take a lesson from the bees, said Wildbrandt.

“Every one of us needs to behave more like a bee society,” said Wildbrandt. “Each one thing we do can add up to something larger than the sum of each one thing.”