Was Kit Carson a Racist or was he an American Hero?

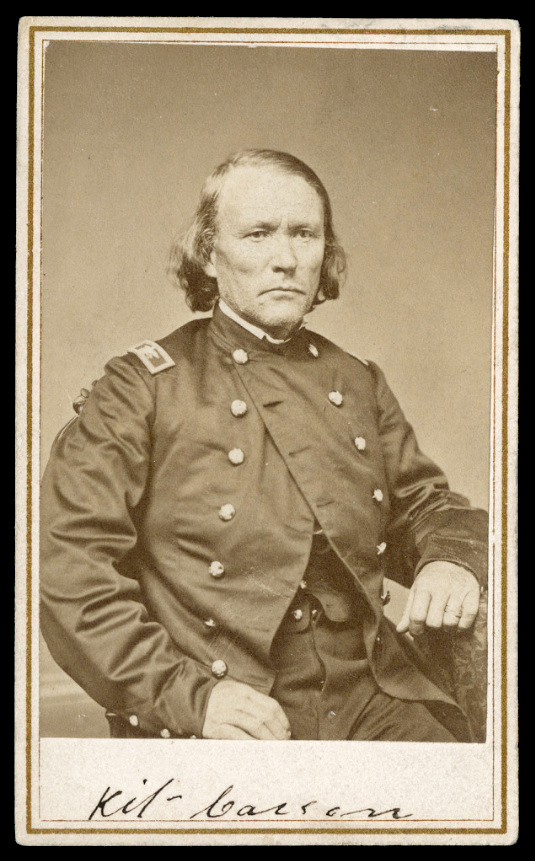

August 6, 2014Photo by paulfrasercollectibles.com

By John T. Bennett

For many Americans, the name Kit Carson evokes several of the greatest elements of the American character: bravery, self-sufficiency, and the thrill of exploration. For some, Carson’s name stands for victory over hostile native tribes. But for one group of ethnic grievance activists in Taos, New Mexico, Carson represents racism and American evil.

Taos is the site of Kit Carson Memorial Park, where Carson is buried. The Taos Town Council recently voted to change the name of the Kit Carson Memorial Park to Red Willow Park. The council has since dropped the name change to Red Willow Park, but the council still plans on renaming the area of the park beyond Carson’s graveyard. But has anyone stopped to ask what Kit Carson actually did, or why he is being slandered?

These questions are part of a deeper, fundamental question about the American identity. Should we feel guilty about the supposed historical injustice of “stealing” native land, or should we refuse to apologize for prevailing in mutual conflict?

“[Kit Carson] was atrocious, an Indian killer,” said Taos council member Fritz Hahn. “We have got to heal the wreckage of the past, and Kit Carson is part of that. The “wreckage” Hahn referred to is the “Long Walk,” a military operation whereby U.S. soldiers, with the help of several Indian tribes, removed the Navajo from Arizona and northwest New Mexico, then relocated them to an area in eastern New Mexico.

Viewed in isolation, the Long Walk seems to feed the narrative that European settlers as a whole were generally unfair towards natives. However, viewed within a historical context, without anti-white or anti-European bias, the Long Walk holds a very different significance.

Who was Kit Carson, and why did he fight some Indians? What did the Navajo Indians do that caused Kit Carson to involve himself in their relocation? These are the questions that should have been asked by the Taos Town Council, and they are questions that inquire into the roots of our national character.

Kit Carson was born in 1809 in Kentucky, and his family moved to the dangerous Missouri frontier when Kit was a young boy. During this time, the Missouri frontier was so unsafe due to raiding Indians that settlers, farmers, and families were forced to seek shelter in forts. Kit’s father was a member of the local militia, and he lost two fingers fighting Indians.

Carson would go on to fight for the Union in the Civil War, and establish fame as a trapper, scout, and soldier. He guided John C. Fremont on the expeditions to Oregon and California, which led to the mapping of the Oregon Trail. In the 1840s, he settled in New Mexico, where conflict had been raging among Indian tribes and Mexicans for generations. The Navajo, in particular, were a source of tremendous tension and violence.

The Navajo viewed non-Navajo groups as “prey,” justifying their “aggressive and thieving impulses,” in the words of R.C. Gordon-McCutchan, former director of the Kit Carson Museum. The Taos Town Council appears to be completely unaware of the Navajo’s conduct towards settlers and neighboring tribes, but it was in fact the Navajo’s conduct that ultimately led to their relocation. In Carson’s day, the challenges faced by New Mexicans were practical and immediate. As Dunlay describes:

“It requires a real effort to recapture the world view of nineteenth century New Mexicans, for whom the Navajos were not the victims of others’ rapacity and racism but the scourges of New Mexico, perpetrators of innumerable raids in which thousands of head of horses, cattle, and sheep were carried off and hundreds of ordinary, unoffending people, herders, and inhabitants of small villages and ranchos were killed or made captive.”

The Navajo had no unified government with which to form treaties that would be binding on all involved. Instead, there were innumerable subgroups that proved nearly impossible to coexist alongside of. Peace treaties were often unenforceable.

By 1861, Navajo raids had resulted in almost 300 murders over an 18-month period. Given the extremely small population relative to current figures, that number of murders would have been seen as an existential threat in the American southwest. It was in this context that Carson became an Indian agent for the Utes and Jicarillas. U.S. officials, unsurprisingly, decided that relocation of the Navajo would be the only effective alternative to perpetual war. The 1864 relocation came to be known by the Navajo as the “Long Walk.”

The Navajo were so disdained that several neighboring Indian tribes joined in the U.S. mission to relocate them.

This is truly a testament to the widespread fear and contempt the Navajo engendered through their own conduct. That important historical fact is totally missing from the current effort to slander Kit Carson, and all that he represents. The historical record is full of very compelling reasons why American settlers, and neighboring Indian tribes, would want the Navajo relocated.

Council member Hahn, claiming to speak on behalf of a “Native American,” said “she feels uncomfortable in the park, which is named after someone who egregiously hurt her people.” For such a person, the thought that “her people” may have hurt American people is beside the point. She has her racial loyalty, and that is the starting point for her worldview. By contrast, Kit Carson does not have an interest group advocating for his heritage and his accomplishments.

Americans should regard Carson as an admirable, central figure in the settlement of the West. At the very least, a reasonable assessment of Carson would include a few essential facts: Carson was called upon to lead armed forces in a civilizational conflict that would paralyze modern men with dread. He did so with distinction and fairness, in the eyes of many. Simmons notes that Carson was appreciated during his life by “Indians, Mexicans and Americans”

Carson’s actions were at times forceful, but he acted in keeping with the established norms of military conduct during conflicts of his day. From a moral and practical standpoint, Carson’s treatment of the Navajo was far more humane than the manner in which the Navajo treated their neighbors and enemies. Given all of this, it is an Orwellian rewriting of our history for certain victim groups to slander Carson.

Let us hope that our national character still contains and preserves some part of Carson’s spirit. To that end, we should at least preserve the name of the state park established in his memory.

Excerpted from a longer article by John Bennett, which can be accessed at www.americanthinker.com.