As cities file suit, feds propose reduction in opioid manufacture

By Bill Dwyer For Chronicle Media — August 28, 2018 As the number of deaths from opioid abuse in America has topped 70,000 in the past year, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Drug Enforcement Administration announced Aug. 17 that they have formally proposed “significant reductions” in the allowable manufacture rate of the most common of those drugs.

As the number of deaths from opioid abuse in America has topped 70,000 in the past year, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Drug Enforcement Administration announced Aug. 17 that they have formally proposed “significant reductions” in the allowable manufacture rate of the most common of those drugs.

The news out of Washington, D.C. comes as officials in several Chicago suburbs have filed suit against several opioid manufacturers, distributors and doctors, seeking permanent injunctions and monetary damages for what they allege is rampant over production, distribution and prescribing of the drugs.

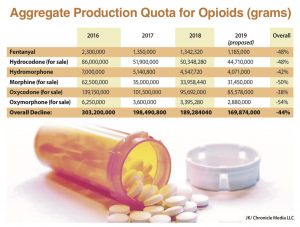

Among the more commonly prescribed schedule II opioids being targeted under the new initiative by the DEA are oxycodone, hydrocodone, oxymorphone, hydromorphone, morphine, and fentanyl.

“The opioid epidemic that we are facing today is the worst drug crisis in American history,” Attorney General Jeff Sessions said in a press release. He touted the federal government’s “significant progress” reducing the number of opioid prescriptions over the past year.

“Cutting opioid production quotas by an average of 10 percent next year will help us continue that progress and make it harder to divert these drugs for abuse.”

The DEA establishes an aggregate production quote for more than 250 schedule I and II controlled substances annually. In that process, it considers data from many sources in setting the APQ for narcotics.

Those include “estimates of the legitimate medical need from the Food and Drug Administration; estimates of retail consumption based on prescriptions dispensed; manufacturers’ disposition history and forecasts; data from DEA’s own internal system for tracking controlled substance transactions; and past quota histories.”

When Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act, the quota system was intended to reduce or eliminate diversion from “legitimate channels of trade” by controlling the quantities of the basic ingredients needed for the manufacture of controlled substances.

Once the aggregate quota is set, the DEA allocates individual manufacturing and procurement quotas to manufacturers that apply for them, and may revise a company’s quota at any time during the year if it believes change is warranted for whatever reason.

“We’ve lost too many lives to the opioid epidemic and families and communities suffer tragic consequences every day,” said Uttam Dhillon, the DEA’s acting director.

“This significant drop in prescriptions by doctors and DEA’s production quota adjustment will continue to reduce the amount of drugs available for illicit diversion and abuse while ensuring that patients will continue to have access to proper medicine.”

The proposed federal enforcement actions come as a class action lawsuit originally filed in Illinois state court in May was ordered transferred to the federal court in Chicago.

That lawsuit was brought by 10 Cook County municipalities and one city in southern Illinois. They include Melrose Park, River Forest, Bellwood, Berkeley, Berwyn, Hillside, Northlake, Chicago Heights, Oak Lawn, Tinley Park and the City of Pekin.

The lawsuit breaks the defendants in three groups; manufactures, distributors and prescribers.

The prescribers named are three doctors — Paul Madison, William McMahon and Joseph Giacchino — who operated alleged “pill mills,” first in a store front clinic in Melrose Park and later in Riverside.

In bringing suit, Melrose Park and their co-plaintiffs state that “prescription opioids are devastating communities across the country and in the State of Illinois.”

Since 1999, they note, there have been more than 351,000 opioid related deaths in the country — six times more than the death toll in the Vietnam War.

In 2015 more than 2 million people in the U.S. had substance abuse problems related to prescription opioids. The annual cost of that epidemic is estimated to be as high as $500 billion nationally.

The Melrose Park suit alleges that opioid manufacturers “purposefully and aggressively marketed opioid products for approved uses, buried unfavorable research and employed a network of phony front groups, opinion leaders, and sales representative to expand the market for opioids and obtain massive profits.”

In 2007, executives of a top opioid manufacturers, Purdue Pharmaceuticals, pleaded guilty to federal charges of misbranding their OxyContin opioid and paid a $600 million fine.

Prescription opioid distributors, the suit alleges, “utterly failed in their duty to provide adequate monitoring of drug volumes and any suspicious activity, and instead “pursued blockbuster profits by throwing open the gates and looking the other way, as millions upon millions of doses of prescription opioids flooded into cities, towns, and villages throughout Illinois.”

As for Madison, McMahon and Giacchino, the lawsuit alleges, they were “working around the clock to prescribe opioids to anyone who came through the door of their clinic … whether or not they had a valid need for them … or presented any number of patently suspicious traits.”

Giachinno operated a clinic in Winston Plaza in Melrose Park from 1985 until 2011, when his medical license was permanently revoked. HIs conduct, the suit noted, “has been so brazen and destructive as to earn him the nickname ‘Dr. Millionpills.’”

McMahon’s medical license was permanently revoked in 2016 for overprescribing of opioids, and Madison’s medical license was suspended in November 2016, also for overprescribing opioids.

The Illinois Department of Professional and Financial Regulation determined that opioid pills from the Riverside clinic were distributed not just locally, but also to clients hundreds of miles away in Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota Wisconsin and six more distant states.

“Defendant’s indifference has taken a dramatic toll on (communities throughout the state),” the suit argues, including “drug abuse, addiction, and crime” that continues to impose “tremendous social and economic costs” on the communities bringing suit.

Among the legal remedies the suit seeks are monetary damages from each defendant, the establishment of an “abatement fund” paid for by the defendants, the payment of punitive and exemplary damages, and all court costs associated with the lawsuit.

—- As localities file suit, feds propose reduction in opioid manufacture —-