BICENTENNIAL 2018: How the University of Illinois wound up in Champaign-Urbana

By Tom Kacich — November 29, 2018

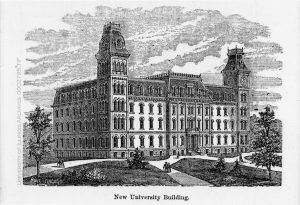

University Hall, which stood on the site of the present Illini Union until it was town down in 1938. (UI Archives)

Champaign-Urbana owes its prominence to the University of Illinois, and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign owes its existence to Clark Robinson Griggs.

If it hadn’t been for Griggs — probably the greatest political operator in Champaign County’s history — the U of I or, as it was then known, the Illinois Industrial University, would have been located in Jacksonville, Lincoln, Bloomington or perhaps Chicago.

Yet, there is no Griggs Hall at the university, no statues of Griggs on campus. Even in Urbana, where he served a year as mayor, there is only a four-block-long street that bears his name.

One can only guess why Griggs’ name has been forgotten by all but the history books. Perhaps the university is just a little ashamed of the man who could be called its father.

You see, Griggs was a bit of a scoundrel.

Much of the story of Griggs’ delightfully sly effort comes from an interview he gave to Allan Nevins (who later became known as the father of oral histories) shortly before his death.

Historians have disputed some details of Griggs’ story, but there seems little doubt that he was an operator who would fit well in today’s Statehouse.

Griggs was a Massachusetts native who came to Champaign County in 1859. He purchased land north of Philo on Yankee Ridge, a place so named because of all the New Englanders who settled there.

At the start of the Civil War, he enlisted in the Union Army and served as a sutler, a man who sold food and drink to soldiers.

After the war, Griggs was elected to the Illinois House. He had already served two terms in the Massachusetts Legislature and apparently had learned a lot there about political maneuvering. Griggs went to Springfield a freshman lawmaker who didn’t act like one.

In a 1915 interview shortly before his death, Griggs told Nevins how he helped bring the university to a swampy, sparsely settled community.

It started with $40,000 appropriated by the supervisors of Champaign and Urbana townships and Griggs’ decision to travel most of the state (everywhere but Jacksonville, Lincoln and Bloomington), meet with other state representatives and build support for Champaign-Urbana.

In five weeks, he said, he interviewed 40 House members and gained pledges from 15 of them.

Next, he met with the governor and lieutenant governor and with the chairmen of the state Republican and Democratic parties. In those conversations he learned that the postwar Legislature would be occupied with a number of special interests.

Southern Illinois wanted a prison; Peoria and Springfield were fighting over which would be the state capital, and Chicago wanted to deepen the Chicago River and develop a system of parks and boulevards. Such knowledge would be important in future vote-trading.

This home at 506 W. Elm St. in Champaign was designed for Clark Griggs, who was instrumental in bringing the University of Illinois to Urbana. (The News-Gazette)

When the Legislature went into session in January 1867, the Champaign County Committee moved into Springfield’s Leland Hotel, where for the next three months it held the principal reception room and a suite of parlors and bedrooms. The rooms were used to entertain legislators and their constituents with either drinks, light refreshments or sumptuous dinners of oysters or quail. Lawmakers were supplied with cigars and theater tickets. Late in the session, Griggs arranged for a special train to take legislators to Champaign-Urbana.

None of the other communities seeking the university had a similar arrangement.

Inside the House Chambers, Griggs showed his skill by running for speaker.

For two days, the House was tied up in endless voting. On the night after the second day, an intermediary visited Griggs and asked what it would take to get him to drop out of the race. Griggs wanted the chairmanship of the Committee on Agriculture and Mechanic Arts — the committee that would hear all the bills about locating the university — and the right to choose its members. He got it, dropped out of the race for speaker and thus was able to control the legislation.

As the session progressed, advocates for the other communities, particularly Jacksonville, wondered why the university location legislation wasn’t being heard in the committee.

Griggs would explain that he had called the committee together but that he couldn’t get a quorum. Then he’d publically announce another committee meeting but privately tell its members not to show up.

This went on until late in the session when Griggs was convinced he had the votes.

Finally, on Feb. 20, the legislation — which named Champaign as the site of the university — reached the floor.

An amendment was made to substitute Jacksonville for Champaign. It failed 61-20.

Another motion was made to substitute Normal. It failed 58-26.

The Old Dormitory, a former seminary, was the first building used by Illinois Industrial University when it opened in 1867. The five-story building, located where the Beckman Institute now stands, was the largest building in the twin cities and was dubbed the “Elephant.” It was torn down in 1881. (UI Archives)

A third motion was made to insert Lincoln for Champaign. It failed 60-21.

Then the legislation naming Champaign was put to a vote and was approved 67-10. The Senate followed suit Feb. 25.

Three days later, Gov. Richard Oglesby signed the legislation.

Opponents charged that Griggs had bought legislators with a “slush fund.” Jonathan Turner, who had sought the university for Jacksonville, said the Legislature had exhibited “a degree of corruption, hypocrisy, drunkenness and debauchery unparalleled in the history of Illinois.”

The state wasn’t even 50 years old. A much greater history of corruption lay ahead.

Tom Kacich of the (Champaign) News-Gazette can be reached at kacich@news-gazette.media.

Editor’s note: The weekly Illinois Bicentennial series is brought to you by the Illinois Associated Press Media Editors and Illinois Press Association. More than 20 newspapers are creating stories about the state’s history, places and key moments in advance of the Bicentennial on Dec. 3, 2018. Stories published up to this date can be found at 200illinois.com.

–BICENTENNIAL 2018: How the University of Illinois wound up in Champaign-Urbana–