Economists see a long, punishing path out of Illinois money woes

By Jean Lotus Staff Reporter — July 10, 2017A sigh of relief swept across the Prairie State when an Illinois State budget was passed July 6, after two years of impasse. But public policy experts think there is still hard work to be done to right the ship.

On top of that, K-12 school funding still must be resolved.

“I call it a ‘petit bargain,’” said economist J. Fred Giertz, emeritus professor at the University of Illinois Institute of Government and Public Affairs (IGPA). “Overriding the Governor’s veto is not really solving our problems long-term.”

The bad news? Recovering Illinois’ fiscal security will cost a lot and take a long time. The good news? The Illinois economy has been much worse — and is slowly improving.

Looking at the big picture, the state has two problems, Giertz said. Over the past 20 years, Illinois has developed a “long-term structural fiscal imbalance” that means spending will outpace revenues — especially with regard to state pension obligations. Giertz is a trustee of the SURS University pension system.

Giertz’s research contributed to the Fiscal Futures Project’s state report, released by IGPA in Nov. 2016 and funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The report tracks all funds in state government and maintains a computer model of the state budget to provide a clear picture of the state’s fiscal affairs.

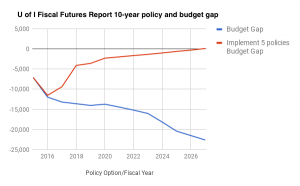

U of I’s Fiscal Futures Report data shows how a 10-year policy can reduce the state’s unsustainable deficit with a policy mix of five changes. (Data courtesy of University of Illinois Institute of Government and Public Affairs)

The report identified an Illinois spending deficit of between $11 billion to $13 billion. On top of that, the gap between pension payments and pension debt is expected to grow by another $15 billion between FY2017 and FY2027, the report said.

The other problem, Giertz said, is a short-term shock that came from reducing income taxes by $10 billion over two years when the state allowed Gov. Pat Quinn’s “temporary” 5 percent state income tax to expire. The tax rate fell back to 3.75 percent, but the state did not make drastic spending cuts.

“The state lost $5 billion in revenue this year and didn’t make any full adjustments,” Giertz said. “On top of that we have pension underfunding and bond payments,” he added.

Giertz said quick fixes have been proposed, like bankruptcy for the state, similar to what happened in the City of Detroit.

“First of all, the state can’t declare bankruptcy. There’s no federal provision for state bankruptcy,” Giertz said. “Secondly, you can’t say discharge unpleasant liability and then keep all the good assets. If it were a true bankruptcy, it would be a cataclysmic situation: Most people focus on [bankruptcy solving] pension underfunding, which is a real problem, but there’s no reason why pension funds would take a haircut and bond holders would not.”

The Fiscal Futures Project’s report recommends a 10-year mixture of five policy changes. These are cutting spending growth by 10 percent per year; increasing personal income tax rates to 5 percent; increasing the income tax base of working people by .5 percent yearly; increasing sales tax base by taxing services (such as lawn-work and haircuts and tattoos) and increasing income growth.

Personal income tax makes up almost half of the total revenue in the state budget. The U of I economists believe about $5 billion per year can be gained by raising the income tax back to 4.95 percent, as was approved in the July 6 budget. As for corporate tax, the state collects about $1 in corporate income tax for every $10 collected from individual tax, according to Illinois Comptroller’s Tax Expenditure Reports. Illinois expects to collect more than $500 million from the corporate tax increase to 7 percent.

The report elaborates more ways to get the state budget back into whack: Consistent, across-the-board spending cuts of 10 percent per year plus growing the income and corporate tax base by stimulating job growth.

A punishing multi-year regimen of program cuts is tough for politicians to stomach, especially Illinois pols, who are not used to saying “no.”

“Lawmakers are facing two unpleasant things, increasing revenue and exercising spending discipline over a multi-year period,” Giertz said. “It’s a choice between two unpleasant options, one is to continue the way we are spending money and not paying our bills and the other is to bite the bullet with more taxes and cuts to reduce the bleeding.”

As for attracting more tax-paying workers to Illinois, growing the economy and building the tax base, politicians disagree on how to make that work. The IGPA report suggests the state’s residents need to see “personal tax base growth of one-half of 1 percent each year.”

Rauner’s unsuccessful “Turnaround Agenda” reforms were meant to draw more job-creating corporations back to Illinois by reforming worker’s compensation laws, weakening unions, along with redistricting reforms and legislative term limits. But other lawmakers have suggested growing the tax base by luring workers with an increase in minimum wage for 2 million workers. Some lawmakers also believe free four-year university or community college tuition, as passed in New York, might also attract productive new residents.

The IGPA report gives a recipe for a slow-but-steady climb out of the Illinois deficit hole: “Our model projects that the combined effect of all of the policy changes we have discussed—substantially reducing spending growth, increasing income tax rates, broadening both the sales and income tax bases, and increasing the economic growth rate—would be just sufficient to close the budget gap if we can implement these policies soon and maintain them over the next decade,” the report said.

How can economists tell if the state economy is improving?

“Surprisingly, the Illinois economy has actually not done that badly in the last couple of years. It’s growing slowly, but still growing,” Giertz said. Giertz and researchers have compiled the U of I “Flash Index” which has tracked economic data monthly since the early 1980s to provide an index picture of the state economy.

“A year ago the unemployment rate was a full percentage point less than the national average, now it’s around 3/10s of a percent less,” he said. With zero growth being a 100 score, the Illinois economy’s yearly average score has been as low as 88 and as high as 110. Right now, the Flash Index score is averaging around 104, Giertz said. A good growth rate would be 105 or 106, he said.

“There is a resilience in the Illinois economy, in spite of all the uncertainties and dysfunction in Springfield.”

School budgets still up in the air

The July 6 budget and spending plans are designed to force the state to adjust school funding according to the “evidence-based model” proposed by Sen. Andy Manar (D-Bunker Hill) in the school funding bill, SB1. Manar worked with a bi-partisan education commission to recommend changes in school funding equity, which is among the worst in the nation. But in the end, Senate Democrats popped the school funding proposal into the voting queue at the very end of the legislative session. Now SB1 is given extra power. At press time, it remained to be seen whether SB1 would be brought before the General Assembly and evade Gov. Rauner’s veto stamp.