Illinois bail reform law draws mixed reviews

By Jean Lotus Staff Reporter — June 19, 2017

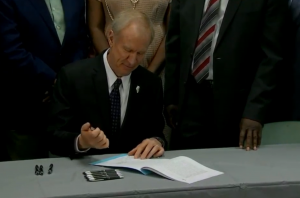

Gov. Bruce Rauner signed his first legislation of 2017 on June 9 with bi-partisan lawmakers and Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx (Center) and philanthropist Willie Wilson (right of Rauner) at Chicago Baptist Institute. (Blueroomstream)

Cash-bail reforms signed into law June 9 by Gov. Bruce Rauner are a good first step, but need more strength to really affect the number of persons who are held in jail because they cannot afford to pay a bond, said bond reform advocates.

Bail reform got an added boost when Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx added some muscle to the new law on June 12 with an announcement that Cook County prosecutors would be recommending recognizance (I-Bonds) in low-level felony or misdemeanor cases.

Sponsors of the Bail Reform Act (SB 2034), Sen. Donne Trotter (D-Chicago) and Rep. Elgie Sims (D-Chicago) said the new law would help fix a system that was keeping people in jail for the crime of being poor.

“By reforming our broken bail system, Illinois becomes a national leader in ensuring incapacitation is reserved for those who are threats to public safety, not those who are poor or suffer from mental health or substance abuse challenges,” Sims said in a statement. Democratic lawmakers were joined by Republican House Minority Leader Jim Durkin (R-Western Springs), Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx and Chicago bail philanthropist Dr. Willie Wilson at the signing at Chicago Baptist Institute.

“The legislation signed today is a good example of forward thinking legislation worked in a bi-partisan manner,” said Durkin in a statement. The law also extended Illinois’s RICO statute, set to expire in June, until 2022.

“We are taking an important step in improving our state’s criminal justice system,” Rauner said about his first legislation signed in the year 2017. “What this does is provide fairness to folks, who are struggling to make ends meet, commit a minor offense, and should not be forced to languish in jail.”

Bail is the total amount of money a judge sets to allow a person charged with a crime to remain free until their hearing. Bond is a percentage of the bail money (usually 10 percent) paid by the defendant to guarantee he or she will show up at trial. If a person cannot post bond for a bail amount, they are kept in “pretrial detention” in custody in a county jail.

But bail reform advocates say money is not necessary to ensure a person charged with a crime returns for a court date. A cash bail system discriminates against poor and minority defendants, they say. Statistically, a person who is held in jail before a trial is more likely to end up in the prison system, advocates say.

Regarding the new law, advocates say reforms don’t go far enough. The changes are “merely the first step toward truly comprehensive bail reform in Illinois,” said Sharlyn Grace, an attorney and criminal justice policy analyst for the Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice.

The new law “doesn’t include any hard limits on money bond,” Grace said. “Judges can still use money bond on every case before them, the same way they can right now.”

The new law allows some people who can’t immediately come up with bond to attend a second bail hearing in seven days. The bill also gives some people a $30 credit toward bond for every day spent in jail.

But Grace predicted those changes would not make a difference in the number of persons incarcerated who are unlikely to be any more able to come up with a large sum within a week. Grace said $30 a day was not enough to work off a large bond sum.

“[M]ost of the harms of pretrial incarceration — such as increased recidivism, the loss of jobs, loss of housing, interference with caretaking responsibilities for children of other dependents — happen after just 24 hours of pretrial detention,” said Max Suchan, co-founder (with Grace) of the Chicago Community Bond Fund. The CCBF has posted “more than $400,000 to free 69 people from Cook County Jail,” according to the organization. Wilson has also posted bond for strangers at Cook County jail, paying $15,000 in September 2016 to release several people from jail.

Grace said one good part of the new law that defendants had the right to a lawyer at the bond hearing. While Cook County does provide access to a public defender at bail hearings, Grace said this new rule would make it easier in other counties for defendants to have a lawyer present.

Sheriff Tom Dart has supported bail reform to allow persons to avoid pretrial detention merely based on inability to pay. The sheriff’s website posts the number of nonviolent detainees who are being held because they cannot afford bond. In mid-June, the Cook County Jail had 9,640 inmates and 152 nonviolent detainees unable to post a bond of $1,000 or less, according to the website.

Dart’s office also believed the new law failed to address another problem: Violent offenders with access to cash — possibly from gang-sources — who can pay a high bond and be released to the streets.

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx added momentum to bail reform by announcing the next week that prosecutors would now be specifically recommending a noncash I-bond for certain cases. Foxx said assistant state’s attorneys had previously participated in bond hearings by reading a “proffer of alleged facts.”

Prosecutors will suggest an I-bond in cases where the person charged had no prior criminal history, crimes were low level felonies or misdemeanors, or there were few “risk factors” that the defendant would not come back to court, Foxx said in a statement.

“Routinely detaining people accused of low-level offenses who have not yet been convicted of anything, simply because they are poor is not only unjust — it undermines the public’s confidence in the fairness of the system,” said Foxx said. “For too long, prosecutors have abdicated our responsibility by not participating in this process. With this policy change, we recognize the role our office can play in decreasing the overreliance on pretrial detention.”

Malcolm Rich, Chicago Appleseed Fund’s executive director said Foxx’s directive would “help to move Cook County away from a money-based system of pretrial justice.”

In October, 2016, two low-income defendants sued the Sheriff Tom Dart and the Cook County Circuit Courts in a class action alleging the courts were violating the constitutional rights of poor defendants by setting unaffordable bond, which held them in jail. The first hearing for the case will take place July 12.

— Illinois bail reform law draws mixed reviews —