The silent threat of HCM

By Kevin Beese Staff Writer — February 26, 2025

Former Steger resident Bill Rossi was diagnosed with HCM in his late 20s. He noted that 1 in 250 people have HCM.

Bill Rossi was a power lifter who worked out with a professional trainer six or seven days a week, but one day just carrying his briefcase down Michigan Avenue in Downtown Chicago left him short of breath.

Jan Berger, who did polar plunges and ran marathons, went in for her annual health check-up and the internist she has had for years noticed something.

“’You’ve got a (heart) murmur, but you’re in good health, you exercise. I’m sure it’s nothing,’” Berger remembers the internist saying.

“I said I was a little slower walking the stairs or an incline. I said, ‘I get tired, but I am also 67 years old,’” Berger said of the 2023 medical appointment.

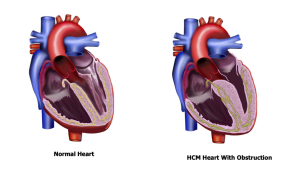

Both Rossi and Berger were diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a genetic heart disease that can affect both the plumbing and electrical systems of the heart. It causes a thickening of the heart and makes it harder for blood to flow out of the organ.

“It is the most common inherited heart disease,” said Berger, a clinical assistant professor at the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine. “It is also the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young people.

“Most people don’t know about it until an athlete or a young person has a sudden cardiac event or death. When that happens, it is most commonly hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.”

Young athletes

Rossi, a local entrepreneur and HCM patient advocate, said 1 in every 250 people have the disease.

“When you see on the news that a young athlete dropped dead on the basketball court, football field or soccer field, it is typically because they have the disease and don’t realize it,” Rossi said. “They don’t know and they do things they are not supposed to do, like competitive sports. That puts them in a dangerous position.”

Today marks National HCM Day, bringing attention on the often-misdiagnosed heart affliction. Between 600,000 and 1.5 million people in the United States are estimated to have the disease.

Jan Berger, a professor at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine, has been diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a genetic heart disease. HCM is the most common inherited heart disease.

“One of the very hard things about HCM is there are people who truly have symptoms for 10, 15, 20 years and are misdiagnosed or diagnosed with nothing,” said Berger, who is also a Chicago-based health care author. “So, (the symptoms) tend to be common things, but when you bring them together,” HCM can be pinpointed.

She noted research has shown that women have a higher rate of hot flashes when they have HCM.

“How do you know the difference from a 45-year-old woman who’s going through menopause and one who has hypertrophic heart disease?” Berger asked. “So, it is very much a challenge.”

The always-active Berger admitted that the first several months after being diagnosed with the disease were difficult, full of mental strain, depression and anxiety.

She said she is now able to exercise, in moderation, but the polar plunges are out.

Nevertheless, Berger said she is happy to be able to remain active.

“It used to be (when you were diagnosed with HCM), ‘Go sit on the couch and wait to die,’” she said.

When first diagnosed decades ago, Rossi did think it was a death sentence.

“I thought I was going to die. The first thing that came into my head was ‘I have a bad heart. I’m going to die,’” Rossi said. “I freaked out … I had to give everything up. I had to stop my whole life. My life came to a complete standstill.”

Lagging behind

Berger said other counties are ahead of the United States in discovering HCM earlier.

“Every athlete in Italy – from small age to adulthood – gets an EKG,whether they have symptoms or not,” Berger said. “They are screening through the use of EKGs.

“In the (United Kingdom), they are doing genetic testing on babies. There are other countries that are doing screening. We are not.”

A Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association graphic showing the difference between a normal heart and a heart with HCM

Berger, Rossi and other members of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association are promoting the Children’s Cardiac Safety Act, proposed legislation aimed at integrating cardiac screenings into routine health care, including pediatric wellness visits and athletic exams.

The act, they said, addresses critical gaps in screening practices as 80 percent of children who die from HCM-related complications are not athletes and often go without any diagnosis of the disease.

Components of the Children’s Cardiac Safety Act include addressing cardiac questions in wellness exams, improving health care provider training, enhancing physicals, adding family education and fostering discussion about family heart history to identify children and families at risk.

HCMA members note that states with cardiac monitoring laws have already reported improved detection rates and outcomes, highlighting the urgent need for national action to save lives through early detection.

Pinpointing disease

Rossi, who was diagnosed with the disease in his late 20s, said that researchers have been able to determine the mutated genes that cause HCM.

He noted his brother has been been complaining of dizziness and shortness of breath. His doctors have told him he doesn’t have HCM.

“But you don’t know unless you get genetic tested,” Rossi said. “It is not a here today, gone tomorrow thing. It happens gradually over time. He might be at the early stages of this and gradually getting worse.

thing. It happens gradually over time. He might be at the early stages of this and gradually getting worse.

“There are also a lot of other things those symptoms can be attributed to, but being in a family with HCM, did he get the luck of the draw and get that gene? Who knows?”

His brother has agreed to be tested, Rossi said.

Rossi believes his lifting of heavy weights brought on the condition earlier than it would have materialized under normal circumstances.

The former Steger resident had a cousin, a fireman, who died his sleep at age 27. It is now attributed to HCM. His mother was diagnosed with the disease in her 70s, and continues to live with it.

“There is a 50/50 pass down rate from parents,” Rossi said.

Berger pointed out that there are several symptoms of HCM: shortness of breath, fatigue, dizziness, a heart murmur, chest palpitations and chest pain.

“None of those are exclusive to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,” Berger said. “People are often misdiagnosed for years. Doctors will say, ‘You’re just not an athlete. You have asthma. You have anxiety.’”

She encouraged individuals thinking they may have the condition to get genetically tested.

kbeese@chronicleillinois.com