A disabled young patient was sent to get treatment. He was abused instead. And he wasn’t the last.

By Beth Hundsdorfer Capitol News Illinois Molly Parker Lee Enterprises Midwest — September 7, 2022

Alex Bandoni/ProPublica (Source images: Whitney Curtis for ProPublica; document and photo from Illinois State Police file obtained by Capitol News Illinois and Lee Enterprises Midwest)

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Capitol News Illinois and Lee Enterprises.

As Blaine Reichard rose from a breakfast table at the Choate Mental Health and Developmental Center in southern Illinois, a worker ordered him to pull up his sagging pants.

A 24-year-old man with developmental disabilities, Reichard was accustomed to workers at the state-run residential facility telling him what to do. But this time he didn’t obey.

“I’m a gangsta! This is how we do it where I am from!” responded Reichard, who, despite his street-tough defiance, still slept with a teddy bear.

Investigators who later came to the scene of the 2014 incident heard various versions of what happened next. But multiple witnesses told the Illinois State Police that shortly after this exchange, Reichard was taken to the floor, held down by four mental health techs and repeatedly punched in the face, according to a 700-page state police investigation obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

Reichard cursed and spat, trying to fight back. His resistance was met with more blows, according to witness accounts. Reichard, whose diagnoses include autism, would later tell police it felt like he was hit 100 times.

Multiple employees, including a doctor, told investigators that Reichard’s injuries were the worst they’d ever seen. One tech told police she vomited at the sight of his injured face.

Located about 120 miles southeast of St. Louis, Choate serves people with the most profound disabilities in the state. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division had cited Choate for failing to protect residents from physical and psychological abuse and other harm. The federal agency stopped short of suing the state of Illinois — a step it has taken against other states — and closed its investigation in 2013, saying in a report to Congress that Illinois officials had made adequate improvements.

The Reichard beating happened the next year, just before Christmas. While it is one of the most egregious examples of abuse of a Choate resident in a decade, a monthslong investigation by Capitol News Illinois, Lee Enterprises and ProPublica has found that the incident is one of many instances of mistreatment at the rural facility managed by the Illinois Department of Human Services.

Reporters from this team filed more than 50 public records requests, reviewing thousands of pages of internal documents from IDHS and its inspector general; the Illinois State Police; officials in Union County, where the facility is located; and other entities.

An image of Reichard’s bed that was included in the police report. Closer images show blood splatter on the floor and the wall. (Illinois State Police report obtained by Capitol News Illinois and Lee Enterprises Midwest)

The documents and interviews with current and former employees and advocates, and with residents and their guardians, revealed a systemic pattern of patient abuse, neglect, humiliation and exploitation.

Over a 10-year period running through 2021, the state police opened at least 40 criminal investigations into alleged employee misconduct at Choate, more than at any of IDHS’s other facilities in southern Illinois.

Using court records and Illinois State Police case files, reporters found that at least 26 Choate employees were arrested on felony charges over roughly the same time period, including four who were connected to the Reichard case. Employees have since been accused of whipping, choking, punching and raping residents.

Among the more recent arrestees are four employees who were accused of choking and beating another Choate patient in 2020, leading to felony battery charges. Two have pleaded guilty to misdemeanor battery charges in exchange for probation sentences and two cases are still pending.

In 2020, an employee was charged with felony battery, for allegedly taking off his belt and using it to repeatedly whip a resident. Then, earlier this year, an employee was charged with criminal sexual assault of an intellectually disabled person who lived at the facility. And in another 2022 case, an employee was charged for allegedly grabbing a nonverbal patient with the mental capacity of a 15-month-old by the neck and punching him in the back of the head as a security officer watched, according to court records. These three cases are still pending.

Over the years, advocates have called for the facility to be closed. “It’s a purely political decision to keep Choate open,” said civil rights attorney Thomas Kennedy, who has provided legal services to Choate patients on and off for decades. “It’s not about helping people. It’s not about habilitating or rehabilitating people. It’s about keeping jobs in the community. Period. They have failed miserably at any other mission.”

In a statement to reporters, IDHS spokesperson Marisa Kollias acknowledged the seriousness of the concerns at Choate. She said that the problems are the “result of longstanding, entrenched issues dating back decades” and that the agency has “taken aggressive measures over the past several years to unravel them.” That includes increasing staffing and training and appointing Equip for Equality, an independent legal advocacy organization, to monitor conditions inside the facility, just as IDHS did in response to troubling conditions there nearly 20 years ago.

Blaine Reichard with his dog, Frankie. (Courtesy of Amanda McIntosh, Reichard’s mother)

A spokesperson for the Justice Department provided the news organizations with the congressional report announcing its official exit from Choate, which included a commitment to continuing to monitor conditions there. She declined to answer additional questions.

Strapped to His Bed for Hours

As the beating of Reichard continued, one of the employees shouted for restraints. Reichard was dragged to his room and bound to his bed with black nylon straps around his ankles, wrists and chest.

An IDHS record included in the police report showed that for almost two hours, mental health tech Mark Allen sat just an arm’s length away from Reichard. Allen had been accused of harming residents on seven previous occasions since he started his employment at Choate in 2011 — and had been cleared to return to work each time.

Colleagues would later tell Illinois State Police investigators that Allen was volatile and moody. He told them he was an Iraq War veteran diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

A fellow resident who walked by the room told police that he saw Allen continue to pummel Reichard’s face even after Reichard was strapped down on his bed. The crime scene photos show blood splattered on the floor and walls of his bedroom.

Allen threatened Reichard with death if he reported that employees had beat him up; made fun of him for not having a girlfriend; and punched him again in the jaw, nose and eyes, Reichard told state police in an interview.

While Reichard was still restrained, Allen sent a text message to a colleague. The text, later obtained by police, read, “we just got done strappin Blaine in… I f***** his world up this morning.” “U guys always do lol…,” she responded.

Fifteen months passed before anyone was arrested. In March 2016, Allen was charged with three felony counts of aggravated battery and intimidation. In October 2016, charges were filed against three other Choate employees, Curt Ellis, Justin Butler and Eric Bittle, who were all accused of helping Allen conceal the abuse and lying to police.

Within a month of being charged, court records showed Ellis cut a deal, agreeing to plead guilty in exchange for a misdemeanor conviction for failing to report the matter to authorities. Bittle and Butler followed suit within three months.

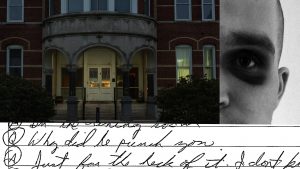

Choate Mental Health and Developmental Center in rural Anna, Illinois, was built more than 150 years ago. (Whitney Curtis for ProPublica)

Nearly seven years to the day after Reichard’s assault, Allen pleaded guilty to a felony, but not for beating Reichard. He pleaded guilty to felony obstruction for destroying evidence by throwing away the bloody towel he’d used to mop up Reichard’s blood. He was sentenced to two years of probation.

Until now, the Reichard case has never been covered in the press. It also did not serve as a deterrent to the alleged mistreatment of residents by employees at Choate.

“The Perfect Victim”

People from across Illinois come to live at the 270-bed facility on the outskirts of the small town of Anna, Illinois. It serves people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, mental illnesses or a combination of disorders. Patients can enter voluntarily or be placed there by a guardian, or a judge may order them to Choate for treatment after finding they’re at risk of harming themselves or others. Many end up living at Choate for years.

Nearly 15% of Choate residents with developmental disabilities have diagnoses in the severe or profound range; about 10% are nonverbal.

“In essence, many of these individuals can be ‘the perfect victim’ for a crime because it is easy to cast doubt on someone who has mental challenges or can’t give a statement due to their mental health status,” said Tyler Tripp, the state’s attorney in Union County.

Choate houses the state’s only forensic unit for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities who have been accused of a crime and found either unfit to stand trial or not guilty by reason of insanity. That’s the unit where Reichard, who had been arrested for attacks on his family, police and medical personnel, initially lived; he was moved to the less restrictive “step-down” unit in 2014. Though Choate includes a small psychiatric unit, a review of records shows that most of the alleged mistreatment has involved patients with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

Records from the IDHS inspector general’s office — the internal watchdog charged with investigating wrongdoing at the state’s facilities — show the office investigated more than 1,500 reports to its hotline that alleged patient abuse or neglect by employees at Choate over a 10-year period ending in 2021. That’s more than any of the 12 other facilities operated by IDHS, some of which have more patients than Choate. Those reports include roughly 800 claims of physical abuse, 100 of sexual abuse and 600 of mental abuse, financial exploitation or neglect.

Internal investigators found about 5% of the cases to be substantiated, roughly in line with the statewide substantiation rate. But advocates acknowledge that while residents of the state’s facilities sometimes file false reports, Choate in particular has faced repeated criticisms from the inspector general, prosecutors and state police for interfering in their investigations into alleged wrongdoing.

The number of abuse and neglect allegations from Choate reported annually to the agency’s inspector general has been steadily climbing for a decade. There were more than 200 reports in fiscal year 2021, the latest period for which data was available. That was more than double the number from fiscal year 2012.

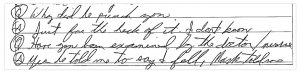

Blaine Reichard’s initial statement, which was given to a Choate security officer, is included in the Illinois State Police investigation file. (Illinois State Police document obtained by Capitol News Illinois and Lee Enterprises Midwest)

In addition to the charges of violence, Choate employees have been the subject of hundreds of other allegations, according to reports from IDHS’ Office of the Inspector General and Union County court files. Among the substantiated allegations are instances when staff tortured and humiliated patients, including one who was marched naked in front of peers as punishment for taking too long in the shower, and another who was forced to drink an entire cup of hot sauce.

The substantiated allegations also include incidents of employees using racial and homophobic slurs, sending sexually inappropriate text messages to a patient, and bribing residents with treats to give the employees foot and shoulder massages, according to OIG reports.

In OIG cases brought between fiscal years 2015 and 2022, employees have also been accused of various forms of neglect, including sleeping on the job and failing on multiple occasions to protect clients with pica, a dangerous disorder that causes people to ingest inedible objects.

In one case, a patient was rushed to a hospital after swallowing a razor blade; while there, under the care of a Choate employee, the patient removed two batteries from a heart monitor and swallowed them. Hospital staff reported that the employee’s feet were propped up, his headphones were on and he was playing on his cellphone.

Kollias, the IDHS spokesperson, said the agency is concerned about the volume of reports of abuse and neglect at Choate, but added that the high number of allegations could also be a sign that staff and residents report potential misconduct at a higher rate than people at its other facilities.

Delayed Consequences

For approximately 48 hours, there was no call to a doctor to treat Reichard’s injuries. There was no call to the OIG hotline to report the abuse, a call that the law dictates must be made within four hours of the discovery of an incident. At least three shifts of workers came and went without raising an alarm, the police report showed.

When security arrived on the unit Monday morning to follow up on an anonymous report, Reichard, his face bruised and swollen, greeted the officer with outstretched arms and said, “Look what they did to me,” according to an employee who was on the unit that day but who is not authorized to speak publicly.

In an interview with a reporter, Allen acknowledged that Reichard had been assaulted but maintained he was not the one who did it. He declined to answer further questions. Butler did not respond to calls placed to a phone number provided by a family member, or to messages sent through Facebook. Reporters sent messages to Ellis and Bittle through Facebook and through a union representative seeking comment; the union representative said both men had been made aware of the story and had been provided with contact information for a reporter, though they did not respond.

While the four men were initially charged with felonies, no one was ultimately held criminally responsible for the beating.

The news organizations’ investigation found that this was not the only incident in which consequences were delayed or minimized. The investigation found that employees who abuse residents or engage in other misconduct face few serious consequences. IDHS does not track employee arrests at its mental health and developmental centers.

Court records show that 22 other employees have faced felony charges since the four arrests in the Reichard case. Of those, 11 pleaded guilty in exchange for their charges being reduced to misdemeanors or were sentenced to probation in lieu of charges, seven have cases pending, and four had cases dismissed.

None of those charged have served prison time.

Allen holds the distinction of being the only employee at Choate convicted of a felony related to patient maltreatment in at least a decade.

Yet neither he nor the other three Choate employees convicted in the Reichard case have been fired. Ellis and Butler were almost immediately placed on leave, as was Bittle when the charges were filed. After pleading guilty, the three returned to work at Choate, mowing lawns, cooking or doing laundry. About three years ago, their status returned to administrative leave. They no longer do any work at Choate, but they still receive a state paycheck today. Since the incident, taxpayers have paid the trio more than $1 million combined. Their annual salaries range between $50,000 and $54,000, IDHS records show.

The three are also receiving their scheduled raises, health insurance benefits, vacation time and service credit toward their pensions. Per their plea deals, their court fees amounted to $807 each, $350 of which was a fine.

John “Mike” Dickerson, the unit supervisor on duty the day of the assault, participated in restraining Reichard, according to police records. Though he was not charged in the Reichard beating, Dickerson was reassigned to mow grass at the facility two years later, records show.

Between when the incident occurred in 2014 and when he retired in December 2017, he received $168,000 in salary, plus insurance and credit toward his pension. He receives $39,000 a year in state pension benefits. Dickerson, reached at home, declined to comment.

IDHS senior officials told reporters in an interview that Allen’s coworkers and supervisor were outliers in terms of the amount of time they spent on paid administrative leave. But agency records obtained via the Freedom of Information Act show 26 Choate employees were on paid leave as of the end June, the last month of the state fiscal year. Eleven have been on paid leave for more than a year. Some of these cases involve employees who were charged with crimes or are under criminal investigation.

IDHS’ spokesperson said administrative reviews by its inspector general typically do not proceed until any criminal investigation is concluded.

“Regrettably, some investigations, which can be conducted by the Illinois State Police, the IDHS OIG, or both, and the prosecutorial decision whether to charge an individual have taken years to complete,” IDHS’ statement read.

A supervisor with the OIG’s office wrote in a May 2020 email to Inspector General Peter Neumer that the internal investigation will rule that the abuse charge against Allen is substantiated, as are the charges against the other three for egregious neglect for “not stopping the abuse, colluding and failing to report,” according to emails obtained by the news organizations. His email from more than two years ago asked if it would be possible to proceed with closing out the case because “it has gone on too long already.”

Senior officials within IDHS and its OIG who spoke to reporters declined to elaborate further on the details of the investigation. With Allen’s guilty plea this past December, the investigation is nearing completion, and depending on the results, IDHS will either pursue discipline or return Butler, Bittle and Ellis to work, the agency’s spokesperson said in a statement.

State police said in a statement that abuse cases are challenging to investigate due to a lack of witness cooperation and corroborating evidence.

While Allen was suspended without pay when he was charged in 2016, he remained on the state payroll during the 15-month period between the time of the incident and the time he was charged, collecting nearly $56,000 while on administrative leave, IDHS records show. He received nearly $2,000 in three additional payments between 2016 and 2019. As a part of his plea deal, Allen agreed to pay fines and court fees of $2,874.

Reichard was discharged from Choate after the assault, but he was readmitted three years ago after he attacked his mother. Deemed by a judge to be unfit to stand trial, he lives in the Sycamore Unit, the same building where the assault occurred.