New Illinois laws take aim at high maternal death rates, racial disparities

By Jerry Nowicki Capitol News Illinois — September 2, 2019

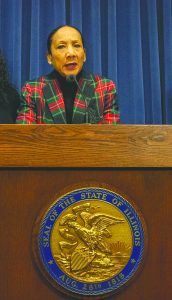

State Rep. Mary Flowers (D-Chicago) said she was moved to sponsor and pass a number of bills aimed at reducing maternal and infant mortality rates in Illinois after a series of news reports and testimony during legislative committee hearings brought the severity of the problem to her attention. “What is happening and what has been happening is truly unacceptable,” Flowers said. (Flickr photo)

SPRINGFIELD — Illinois is taking steps to combat troubling maternal and infant mortality statistics after one lawmaker was moved to action by a series of reports which showcased the state’s and country’s maternal health shortcomings, particularly among African-American women.

The lawmaker is Chicago Democrat Mary Flowers. The troubling statistics: Pregnancy-related complications kill more mothers in the United States than in any other developed country, and African-American mothers die at three to four times the rate of white mothers.

“What is happening and what has been happening is truly unacceptable,” Flowers said. “I can only go back to the articles that I read about the unconscious bias and untreated conditions and unrecognized factors that lead to poor outcomes when it comes down to African-American women and women of childbearing age. It’s unacceptable.”

Last week, Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed the last bills from a package of new laws to create new maternal legal rights and a task force to study the high death rate among African-American mothers and babies, to force hospitals to collect more accurate data on maternal mortality and be better equipped to treat pregnant women, and to mandate proper training for medical staff that are likely to treat pregnant women.

Troubling Statistics

The U.S. weakness in maternal health care was detailed in a 2017 study by National Public Radio and ProPublica which showed 26.4 of each 100,000 mothers in the U.S. died from pregnancy-related complications in 2015, while the next closest developed country was the United Kingdom with 9.2 per 100,000.

The racial disparities are driven home in a report by the Illinois Department of Public Health which said an average of 73 women in Illinois died each year from 2008 to 2016 within one year of pregnancy, and African-American women were six times more likely to die of a pregnancy-related condition during that span. According to the report, 72 percent of those deaths and 93 percent of violent pregnancy-associated deaths were preventable.

State Sen. Jacqueline Collins, a Chicago Democrat and Senate sponsor of several of Flowers’ maternal health care measures, said the disparities existed across income and education levels.

“We found that a lot of highly educated black women in high paying careers are more likely to die as a consequence of childbirth than a white woman without even a high school diploma,” she said.

Flowers said a 2018 New York Times Magazine article which also caught her attention detailed that, in the U.S., African-American infants were more than twice as likely to die than white infants, at 11.3 deaths per 1,000 babies and 4.9 deaths per 1,000 babies, respectively.

While infant deaths have decreased to 30 times less than what they were in 1850 for African-American babies, the number decreased by 44 times for white babies, making the disparity between the races even larger today than it was during that pre-Civil War era.

“That was more than a decade before the abolishment of slavery,” Flowers said. “Now, that tells me there’s some real problems here in the United States.”

Collecting Accurate Data

In response to the reports, Flowers called two committee hearings last year which she said brought forth further revelations.

Her committee heard testimony about poor hospital funding and readiness to handle childbirth in certain communities, obstacles to continuity of care and poor documentation of pre-existing conditions for people with low incomes, and systemic bias and racism in the medical profession which leads to stress on patients and their health concerns sometimes being ignored by doctors.

“Doctors testified to racism, and they also testified to implicit bias and all other kinds of problems that needed to be addressed as well as training,” she said. “And we know that more women are dying from something as simple as hemorrhaging, and it’s not being addressed.”

To look further into the driving forces of maternal and infant mortality rates, Flowers sponsored and unanimously passed House Bill 1, which was signed by the governor in July to create the Task Force on Infant and Maternal Mortality Among African Americans.

The task force will be comprised of state health officials, doctors, midwives and medical professionals, hospital and insurance leaders, community experts in infant and maternal health, and an African-American woman who has experienced a traumatic pregnancy.

The task force will meet quarterly and report findings to the General Assembly by Dec. 1, 2020, on the causes and rates of maternal death and ways to improve the quality and safety of maternity care.

State Sen. Jacqueline Collins speaks during a news conference March 6 at the Capitol in Springfield. Collins (D-Chicago) sponsored several Senate bills aimed at reducing the state’s maternal and infant mortality rates. Among the statistics is that African-American mothers die at three to four times the rate of white mothers of pregnancy-related complications. “We found that a lot of highly educated black women in high paying careers are more likely to die as a consequence of childbirth than a white woman without even a high school diploma,” she said. (Photo by Jerry Nowicki/Capitol News Illinois file)

“It’s been well known in African-American communities that there were certain disparities in care and how doctors perceive our pain, but we never had the data to back it up, or to make that determination,” Collins said. “And so this is really getting at it.”

Another measure, House Bill 3, requires hospitals to include in each of their state-mandated quarterly reports any instances of preterm infants, infant mortality and maternal mortality, and the racial and ethnic information of the mothers in those instances.

Collins said accurate data is necessary to more clearly define the problem in Illinois, and “just to put the issue on the radar screen.”

“We want to hold hospitals accountable so we can have accurate data and gauge the scope of this problem,” she said. “This task force will focus on a data-driven approach to crafting policy.”

Maternal Rights

House Bill 2 is another unanimously-passed bill in the maternal mortality package, and it adds 19 new rights for pregnant women to the Medical Patient Rights Act. The Act was established in the 1990s, laying out rights for medical patients that, if violated by a health care provider or insurance company, can result in a fine ranging from $500 to $1,000.

House Bill 2 adds to that act, giving a woman the right to receive health care for herself and her baby before, during and after childbirth, to be treated with respect at all times, to contact with her baby when medically possible, and to refuse any treatment to the extent medically possible.

A woman also has the right to choose a certified nurse midwife or physician as her maternity care professional, to seek different caregivers if they are unsatisfied, to know the names of those providing her care, and to receive information about her condition and possible treatments.

Women also have the right to receive medical information in a language they understand, and to receive information about breastfeeding.

As well, a woman can choose her birth setting from a full range of options in her community, be informed if caregivers enter her or her baby in a research study, and has a right to give birth in the position of her choice within generally accepted medical standards.

“These rights show that a woman is to be respected,” Flowers said.

The bill also gives a right to privacy and confidentiality, emotional and physical support during childbirth, and the ability for a mother to decide collaboratively with caregivers when she and her baby will leave the birth site.

Finally, women have the right, regardless of how they are paying for their stay, to receive an explanation of the total bill for services, including itemized charges for specific services received as part of her maternity care.

“We know that patients have rights, but it’s unfortunate that we need to enumerate them, the kind of rights that should be so basic, and universally understood,” Collins said.

Other Measures

Another of the bills which received unanimous approval, House Bill 5, directs the Department of Human Services to ensure pregnant and postpartum mothers have access to substance use disorder services that are gender-responsive and trauma-informed.

House Bill 2433, which passed 56-0 in the Senate and 111-2 in the House, requires every hospital to have the proper instruments available to take a pregnant woman’s blood pressure.

House Bill 2438, which also passed unanimously, amends the insurance code to require insurers to cover any mental health condition that occurs during pregnancy or during the postpartum period.

House Bill 2895, which passed the House 109-2 and the Senate 55-0, requires all birthing facilities to conduct continuing education yearly for all staff that may care for pregnant or postpartum women. That training must include modules on management of severe maternal hypertension and hemorrhaging.

Jnowicki@capitolnewsillinois.com