Chicago welcomed 30,000 Japanese internees after Pearl Harbor

By Jean Lotus Staff Reporter — December 7, 2016

Japanese young people in Chicago in 1949 (from left) Bob Kubo, Heidi Kubo, Heidi Okihara and Paul Hiramura. (Photo courtesy of Shiuko Sakai Collection, Oregon Nikkei Endowment/Densho Encyclopedia Digital Collection).

A little-known episode in Chicago history after the Dec. 7, 1941 Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor appeared in the 2000 obituary of Leonard Japp Sr., also known as the “Potato Chip King.”

Japp, who died at age 96, sold snack foods in Chicago. After Pearl Harbor plunged the nation into war 75 years ago, the company changed the name of “Mrs. Japp’s Potato Chips” to “Jay’s Foods. “

“The grocers who carried Mrs. Japp’s Chips wanted them out of the stores pronto, due to all the anti-Japanese feelings at the time,” Japp told the Chicago Tribune. “We had to rename our company fast. The name Jays was available so we made it Jays Foods.”

The ethnic slur for “Japanese” was not new during World War II; it had long been used in California and the western United States according to Bill Yoshino of the Japanese American Citizens League, Chicago Chapter.

“That term had been directed at members of the Japanese community ever since the turn of the century,” Yoshino said. “It reached its peak usage during World War II because we were at war with Japan.”

The three-letter slur was also a great fit for newspaper headlines: On Dec. 8 the Chicago Tribune used it twice on the front page: “U.S. AND JAPS AT WAR” and “Jap Raiders Bomb Two Isles in Philippines.”

But Chicagoans who allegedly rejected Mrs. Japp’s salty treats in 1941 actually had very little exposure to people of Japanese heritage, said Peter Alter, historian at the Chicago History Museum.

“There were maybe 300 Japanese residents of Chicago before World War II, and they were dispersed throughout the city,” Alter said. “They didn’t really have their own neighborhood. I think [the reaction to the word ‘Jap’] was part of a national hysteria,” Alter said. “If you look at the LIFE magazine from Dec. 1941, you’ll see an article ‘How to Tell Japs from the Chinese,’” he said.

Chicago may have rejected the name “Japp,” but when real Japanese came to the city, a few years later, they found a relatively welcoming environment, Yoshino said. In 1943-45, tens of thousands of Japanese internees left camps in the south and southwest often with a few dollars and a handful of meager possessions. Their first stop was Chicago, he said.

“During the war, after about two years or so, individuals at the camps could get ‘leave clearance’ if they could show they had a job or family or a place to go. However, they couldn’t return to their homes on the west coast, which were still considered security zones, so about 30,000 came out of those camps to Chicago to find jobs.” Chicago was the largest population center of Japanese internees in the U.S., he said.

“Word got back to the camps that Chicago was a place they could get jobs, and employers in Chicago were pleased with the types of employees they were getting,” Yoshino said. “Many people regarded Chicago as being hospitable toward the Japanese in comparison to the treatment they had in California before they were kicked out of their homes. You weren’t running into the depth of hostility they had experienced pre-war in the lead-up to incarceration.”

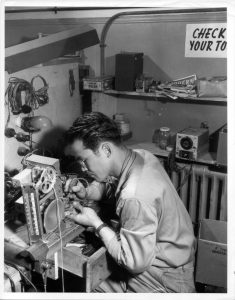

M. Mori of Chicago, a radio repairman with the Allied translator and interpreter section, Tokyo, Japan, works at repairing a radio in the repair shop in September 1946. (Photo courtesy of Seattle Nisei Veterans Committee and the U.S. Army/Densho Encyclopedia Digital Collection).

“Public Opinion Kind in Chicago” reads a headline on the front page of a May 1943 camp newspaper, the Manzanar Free Press

Within three months of the Pearl Harbor attack, in February 1942, Japanese Americans on the west coast were classified as a “security risk” by Gen. John DeWitt of the Western Defense Command, Yoshino said. President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 Feb. 19, 1942, which ordered the removal of 120,000 Japanese residents in California, Oregon and Washington state, almost half of whom were “Nisei” or American citizens,according to the online encyclopedia of the Seattle-based Japanese history and advocacy group Densho Encyclopedia.

The forced removal of Japanese citizens from their homes, farms and businesses was also pushed by interest groups who wanted their property, the Densho Encyclopedia said.

DeWitt even opposed Japanese citizens entering the armed services. “[T]here isn’t such a thing as a loyal Japanese and it is just impossible to determine their loyalty by investigation — it just can’t be done,” he is quoted as saying on the Densho website. Nonetheless, 14,000 Nisei men left the camps to volunteer for the 42nd Infantry Regiment, a segregated Japanese-only unit. The unit served in Europe and was highly decorated, Yoshino said.

Chicago had a booming war economy and jobs were plentiful, Alter said.

“Generally, the folks who were coming were American citizens, native born, and English was their first language,” Alter said. “They were migrants, not immigrants. They had an easier time than displaced persons or “DPs” who came to the U.S. later after the war.”

When internees were allowed to leave the camps, they arrived with very little.

“[Internees] were given $25 and a train ticket to where they were headed,” Yoshino said. “They were allowed to take only what they could carry when they were forced out of their homes, so they had very little and had to start again.”

Japanese neighborhoods popped up on the North Side near Clark and Division streets (where the Chicago History Museum stands today) and in the south side Woodlawn neighborhood, Yoshino said.

“These were not necessarily nice neighborhoods,” he said.

Internees still faced housing discrimination when they got to Chicago, remembered one woman in an oral history video on the Densho website.

“[M]y daughter and I walked and walked and walked, and we walked all day long. And everywhere we went, there would be a ‘for rent’ sign. We’d get there, they’d say, ‘Oh, it’s rented already, rented already,’” said Peggie Nishimura Bain, of Seattle, in 2004. After the war, some former internees returned to their homes in the western U.S., but many stayed in Chicago and the neighboring suburbs.

“[T]here’s a lot more freedom,” remembered former internee Kiyo Yoshimura of Skokie on the Densho website. “If we wanted to do some things, I think we would just go ahead and do it. It [was] freeing us from our past so that we [were] venturing into some new territory that [had] a lot of potential and possibility.”

The Japanese American Citizens League was formed in San Francisco in 1929 to address discrimination toward Japanese citizens, Yoshino said. Some examples were the “Alien Land Law” passed in California forbidding Japanese from buying land, miscegenation laws forbidding marriage between Caucasian and Japanese people and blocked paths to citizenship.

“Japanese couldn’t become naturalized as citizens until 1952. They were the last group to achieve naturalization rights.”

Segregated schools, being prohibited from certain careers and even being barred from cemeteries were some of the issues the League has taken on.

Defamation has always been a concern, said Yoshino.

“The slurs used during World War II had a propaganda use: To demean the enemy and make him as sub-human as possible,” Yoshino said. “The lessons of World War II are lessons we need to heed today. In the last year or so, this whole notion of ‘not being politically correct’ has emboldened many individuals to be less civil than they otherwise would be. The use of slurs is out there more than before,” Yoshino said.

“We are very interested in trying to defend the rights of others, so when there’s talk of anti-Muslim or anti-Arab American [sentiment] we have an obligation to speak out. It harkens back to what happened to us during World War II.”

“The incarceration of 120,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor was a tragedy of American history,” wrote Natasha Varner of Densho in an email. “As an organization tasked with preserving that history, Densho is committed to speaking out when we see similar patterns in American society today. We have taken a stand against the proposed Muslim registry and Islamophobia, against family detention of immigrants, and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.”

As for the negative reaction to Mrs. Japp’s Potato Chips, Alter said the episode may have been an example of fear of the unknown.

“The unknown is even more dangerous and fearful than the known,” he said. “Chicago went from almost no Japanese [in the city] to thousands. [Chicago] was relatively accepting of these Japanese internees when they arrived in the 1940s and many of them stayed here and built businesses and established successful lives and Japanese communities.”

Read the current issue of the Cook County Chronicle

Free subscription to the digital edition of the Cook County Chronicle

— Chicago welcomed 30,000 Japanese internees after Pearl Harbor —