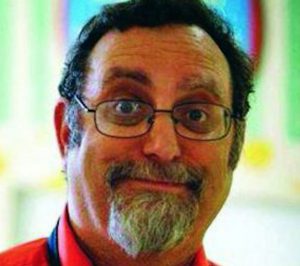

Leavitt: A primer on living with dying alone

By Irv Leavitt for Chronicle Media — April 29, 2020The music played, and I remembered what it was like to lose love forever.

Brahms Clarinet Quintet, Opus 115. I’d never heard it before, and I didn’t know much about Johannes Brahms. But I could tell that he knew where love goes after it’s stolen in the middle of the night.

The music historians say he lived much of his life with a broken heart.

For wounded music lovers, and those with other passions, there may come, with time, a moment when heartbreak is so palpable that it can be felt squeezing the center of one’s chest.

It spreads out from there. Painful and numbing at the same time, it moves around to the small of the back, and upward, to make the shoulders shiver. It takes over thought.

Emotion breaks, and in its wake, something may change. Love thought stolen away forever may return as an almost tangible gift that you can open at will. Yours to husband or to share. Yours to inspire forgiveness of others and yourself. Yours for good and always.

The music doesn’t make it happen. It just reminds you that it happened, that it’s possible.

The plaintive notes of the strings flood in, and then they recede, and then the clarinet comes back fuller than before, and suddenly, it’s not just Brahms’ music anymore. It’s yours.

Brahms, they say, was a lonely man. He knew great loss. Soon, you may, too, if you haven’t had the experience already.

Many people around the world are now losing loved ones before they’ve had a chance to prepare. Family members and friends struck by this awful plague are quarantined after they’ve sickened, and they’re cut off from them.

I hope you’ve been spared this tragedy. Your luck may not last, however.

There’s something you should do right now, so that when the time of heartbreak comes, there’s a gift of love to receive.

I know about these things. Death and I are on a first-name basis.

Death has come to my house, and I have also gone to meet him. I have argued with him. Won a few and lost quite a few more. He has made off with almost all of those I have held dearest. He tried to take me. And at times, I have helped him in his work.

I have tried to prepare for most of the deaths in my life, sometimes well and sometimes badly. I believe that if we ever want to wrap ourselves around that gift of lost and returned love, we have to prepare consciously, and fill the package in advance. We do that by saying the things we need to say to our loved ones now.

They need to know we love them, and that we forgive them and ourselves for everything that ever pushed us apart.

And if they are separated from us while still alive, we should know the depths of our love for each other long before the gurney rolls down that cold and brightly lit hall.

The issues that got in the way can be talked about now. Most of them can’t be that hard to deal with if they haven’t completely ruined our relationships already. And if they’re really that tough, just let them go.

After all, we should try to love our families and close friends the way our dogs love us. Unconditionally. What good is it to harbor resentments? Did anyone ever pass on while wishing they had held more grudges?

If we settle our lives before we’re separated, the fact of our dying alone may be easier.

Mostly, we must admit, the tough part about dying alone is usually on the survivors.

When you’re dying in America, you typically enter a new community of health professionals who minister to you. They become your familiars.

It’s often a strain to respond to visitors, who sometimes come because they yearn for a connection with the sickened person. If you’re still searching for that connection when life is slipping away, you have probably waited too long.

A friend of mine told me that when she was unexpectedly dying one night, beyond the knowledge of her family, she didn’t care at all that there was no one there for her. Donna knew she was loved, so she just left it up to the nurses and doctors to do their jobs, and after they saved her, she had no regrets that her family had been absent.

I remember, years ago, as a severely burned firefighter awaited his life’s end in a clean room where non-staffers weren’t allowed, his visitors remained in another room. It wasn’t ideal, but his fellow firefighters and family members were able to commiserate without disturbing him.

Two people I know of who were on ventilators before their recent coronavirus deaths were largely unresponsive to communication for days before their passing. Their loved ones spent their time comforting each other. That probably did the most good, anyway.

Before my own wife died in 2011, her sickness entered her brain, and communication became upsetting to everybody. Sometimes, memories of the vigils of waning life, tainted by the unfortunate circumstances of disease, compete against a lifetime of much better moments.

But that didn’t last forever, because we knew who we were before the trouble started. And later, I had my moment of trading heartache for heart renewal.

I’m grateful for that moment, which I remember well today. It gave me a little storehouse of love that I draw on when I need it. It made me almost whole, almost normal.

I wish that all of you who are fated this year to lose the most important people in your lives have the same experience.

And I hope you all find clarinet players who know Brahms.