Morton College supersized police force has deep local ties

By Jean Lotus & Bill Dwyer Chronicle Media — April 13, 2016

A Morton College squad car is parked in front of the gym building at the Cicero community college. (Photo by Jean Lotus/Chronicle Media)

Morton College is one of the state’s smallest community colleges. About 5,400 students take classes in four buildings with a footprint of about two city blocks in a residential corner of Cicero.

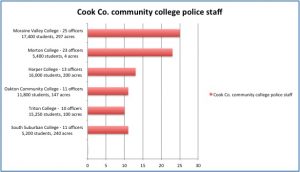

But for a small institution, Morton College has a jumbo police presence. The school police department employs 30 people to patrol a four-acre campus, including four full-time and 19 part-time officers and eight dispatchers.

In 2012, according to a Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the college spent $780,000 on campus security. Among neighboring suburban Cook County community colleges, Morton has the highest ratio of officers-to-students, an analysis shows.

For comparison, South Suburban College, with two campuses near South Holland has 5,200 students on 240 acres and employs a total of 11 officers. Triton College in River Grove has two campuses on 100 acres and a student enrollment of 15,250. Triton employs 10 officers. Oakton Community College has two campuses on 147 acres and 11,800 students with 11 police officers. Harper College employs 13 officers for a 200-acre campus with 16,000 enrolled.

Moraine Valley College employs more officers than Morton — 25 — but with an enrollment of 17,400 and a 297-acre campus.

As far as campus safety, reports show Morton has very little crime. Even though Cicero is known for gang activity, Morton’s 2015 Annual Crime Statistics and Campus Safety report showed 18 thefts and one auto theft during the year. The campus hasn’t reported an assault since 2012.

On Illinois college campuses, a school security force is traditionally staffed by retired and part-time police officers, who often supplement their pension income with a second job. As Illinois colleges face a funding crisis brought on by the state budget impasse, some campuses are cutting costs by hiring “school resource officers” without the full duties of sworn officers.

But Morton College appears to be bucking that trend.

Officer pay at Morton may not be great, but benefits and pension perks are generous.

Full- and part-time union officers are paid $15-$17 an hour with a 3.5 percent raise yearly, according to their most recent contract. Even part-time rank-and-file officers and dispatchers are entitled to health insurance benefits, enrollment in the State University Retirement System and free tuition reimbursement.

Full- and part-time union officers are paid $15-$17 an hour with a 3.5 percent raise yearly, according to their most recent contract. Even part-time rank-and-file officers and dispatchers are entitled to health insurance benefits, enrollment in the State University Retirement System and free tuition reimbursement.

Department brass earn between $50,000 and $80,000, while eight others average between $25,000 and $28,000. With benefits and a pension, most of these officers are raking in a respectable salary.

Public compensation and pension documents from 2013, the latest year available, obtained by the Freedom of Information Act, show how part-time officers at Morton’s close-knit police department earn a significant income. One officer retired from the Illinois Secretary of State police department, from which he receives an $84,000 annual pension.

Retired Berwyn Police Chief Frank Marzullo, the campus’ executive director of public safety, receives a $140,000 pension yearly from the City of Berwyn, according to transparency website www.openthebooks.com. Morton College paid Marzullo $87,843 in 2015, according to the Illinois Community College Board.

Campus Police Chief Leonard Rutka is retired from the Cicero force. Rutka’s Cicero pension pays around $62,000 a year, and his Morton salary was $67,000 in 2013, websites show.

Neither Marzullo nor Rutka responded to emails for comment.

“Institutions of higher learning are often very large parts of state or county budgets,” said Stephen Larrick of the Washington, D.C.-based Sunlight Foundation. “There are significant amounts of public dollars and often the highest-paid public employees are members of a university. We’ve decided with our budgets that these are important ways to spend public money,” he said.

“Universities and community colleges are charged with hugely important tasks and we need them to be effective.”

Morton does not post salary information on its website, nor annual financial reports and audits. The board of trustees does not share board documents with the public, other than the agenda.

Perhaps because the board is so low profile, the police department has grown based on deep local ties and collegial relationships. Five other officers are retired from either Berwyn or Cicero police departments. Additionally, three part-timers are currently employed by the Town of Cicero, Cicero School District 99 and the Berwyn auxiliary police. The brother of a Berwyn alderman works as a part-time police officer. The daughter of a Cicero town elected official is a part-time dispatcher.

Morton College police personnel are also supporters of local politicians. Political campaign contribution data from the Illinois State Board of Elections shows since 2009, 10 officers and a dispatcher donated $16,200 to campaign committees for Cicero Town President Larry Dominick. Three officers have been paid as Dominick campaign workers.

Also, three officers have donated $2,000 to committees associated with Berwyn Mayor Robert Lovero. One officer was paid $2,000 by the Lovero campaign. A dispatcher was paid for campaign work by House Speaker Michael Madigan’s Democratic Majority Committee. Two officers have made $500 donations to General Assembly Democratic leaders and State Sen. Martin Sandoval.

The school serves a largely low-income population with a high percentage of immigrants. Morton is designated a Hispanic Serving Institution by the federal government. Morton College receives about $10 million in federal aid yearly, almost half of its $22 million budget.

But dollars are getting harder to find. Morton is among the Illinois community colleges hardest squeezed by the Illinois budget stalemate. The district has a budget gap of $6 million in state funding, or about 26 percent of its operational expenses, according to the Illinois Community College Board. Additionally, the state has not paid $870,000 of Monetary Award Program (MAP) grants for the 2015-16 school year. Funds for student daycare and adult education have already been targeted to cut.

Larrick argues the way to get stakeholders to understand and value the expenses of the college is to become more transparent by posting financial and board documents online.

“There is a question of trust,” Larrick said. “The way public institutions in the 21st Century build trust is by opening the data and allowing the public to see under the hood and participate, especially with a fiscal crisis. People want to know how we are slicing the pie when there’s not enough to go around.”

It remains to be seen whether the college will look for cost savings by cutting the police department, or whether those steps would even make a difference in the school’s bottom line.

“With little actual crime, why is the college over-staffed on its police force?” asked transparency advocate Adam Andrzejewski, Elmhurst-based CEO of Openthebooks.com.

“It certainly looks like an employment farm for the politically connected insiders, and not manned to meet true law enforcement needs,” he added.

“Some personnel are expensive, and there are times when people get overpaid,” Larrick said. “But by putting the data out there, not just analyzed internally, comparisons can be made [to other colleges] and you build legitimacy that goes along with trust.”

— Morton College supersized police force has deep local ties —