Behind Art Institute’s new Arms and Armor exhibit

By Jean Lotus Staff reporter — April 3, 2017

John Tavares, curator of the Art Institute Arms and Armor collection, stands in the museum’s new gallery. (Chronicle Media)

In a 1937 photo, the smartly dressed museum curator perches at his workbench, surrounded by metalworking tools, a knight’s helmet and medieval battle axe.

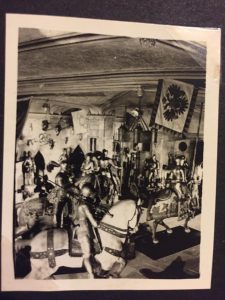

Antique photo scrapbooks from 1924-40 have helped the Art Institute of Chicago better understand the George Harding II arms and armor collection acquired by court decree in 1982.

After four years of planning, the museum unveiled in March more than 1,000 pieces of heraldic hardware from the collection — for war, tournament and adornment — along with a collection of historic firearms. Pieces are displayed in the new Saints and Heroes medieval and Renaissance wing. About 45 percent of the Harding collection is displayed, the “best of the best,” said Jonathan Tavares, arms and armor curator.

Compiled by the collection’s first curator and caretaker, Kyotsugu Tsuchiya, the early scrapbooks show images of the original Harding Museum in Hyde Park. Tsuchiya’s granddaughter, Lourdes Nicholls, of Oak Park, lent the scrapbooks to the Art Institute in 2015. Nicholls recognized the collection in 1990 when she moved to Chicago from California. She had just interviewed her 90-year-old grandfather about his experiences during WWII at the Manzanar internment camp near California’s Sierra Nevada mountains.

Lourdes Nicholls, of Oak Park, holds one of her grandfather’s vintage photo scrapbooks. (Chronicle Media)

Tsuchiya, then 90, told his granddaughter about his early years in Chicago as an Art Institute student hired to maintain the opulent and iconoclastic private collection of George Harding II.

Kiyotsugu Tsuchiya, curator of the George Harding Museum at his workbench in 1937. (Photo courtesy Lourdes Nicholls)

“When I saw the armor at the Art Institute for the first time, I told my husband, ‘This has to be the armor from my grandfather’s museum,’” Nicholls said.

She attempted to contact the curator, Leonid Tarassuk, but found he had just died in an auto accident.

The collection was under wraps for decades and then largely held in storage at the art museum, where only 10 percent was on display.

But in its heyday, the collection reflected the taste of Harding himself.

George Harding II was the wealthy son of a successful Civil War officer and a 1920s Chicago Republican politician and real estate magnate.

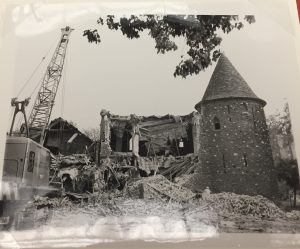

He traveled the world in a private plane, amassing a cache of paintings, rare antique musical instruments, original Remington bronzes and other treasures. The collection was housed in a wing of Harding’s home built to resemble a German castle in the 4800 block of Lake Park Avenue.

Tsuchiya served as a live-in caretaker and curator for the collection. Called “Bill” by visitors, Tsuchiya gave private tours to visitors, including Al Capone.

Harding’s arms and armor collection was often purchased from liquidated estates of cash-hungry European nobles during the global depression leading up to World War II, said Tavares.

“He had the money, and they needed it,” he said. Harding competed with rival armor collector William Randolph Hearst for the best pieces.

“[Tsuchiya’s] photo albums filled a huge gulf,” Tavares said in a 2015 interview. “They show the castle as it was lived in during, and just after, Harding’s day. The photos offer vantage points we had not seen and, most importantly, they tell how the pieces were distributed and organized.”

Tavares, a former curatorial fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, studied the Ivanhoe-inspired Victorian obsession with collecting arms and armor in graduate school. The new exhibit pays homage to Harding around the top of the armor room where panoplies of pole weapons, halberds, axes and spears are fanned, as they would be above a Victorian fireplace.

“We wanted to capture the spirit of Harding’s display and the idea of that chivalric legacy,” Tavares said.

The man who first created those displays was to have a difficult path in life.

Kyotsugu Tsuchiya married his wife, Chie, in Los Angeles on Dec. 7, 1936, exactly five years before Pearl Harbor. The two returned to Chicago, where Chie opened a small restaurant serving “Dainty Japanese Dishes.”

But Harding died unexpectedly in 1939, leaving his assistant (and likely mistress) Jessie Katz as manager of the collection, which had by then become a “free museum,” according to local newspaper reports.

The Tsuchiyas decided to return to California in 1940, bearing a letter of recommendation from Katz saying Kyotsugu had worked for the museum for 14 years. “He was found to be honest, trustworthy, reliable and capable. We regret very much him leaving this corporation and recommend him very highly,” the letter said.

The Harding Museum building is torn down for road expansion in 1965. (Photo courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago)

The couple moved to Los Angeles and purchased a small nursery business, just in time for their lives to change forever.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 within two months, requiring persons of Japanese ancestry to report for “evacuation” from coastal areas. Detainees could only bring a single bag of possessions, and Tsuchiya had to sell his nursery to the milkman for $75, he told his granddaughter.

The scrapbooks and other important papers were hastily stored in a Buddhist temple in Los Angeles, according to the Tsuchiyas’ daughter Fumi Knox.

The temple was an emergency repository for many Japanese residents.

“In L.A., the Nishi Hongwanji [Buddhist temple] served as a warehouse for inmate belongings, watched over by Rev. Julius Goldwater, the lone Buddhist priest left in L.A., since he was white,” said Densho.com Content Director Brian Niiya in an email.

Based in Seattle, Densho is a “history non-profit dedicated to preserving the and sharing stories of the Japanese American past in order to promote equity and justice today.”

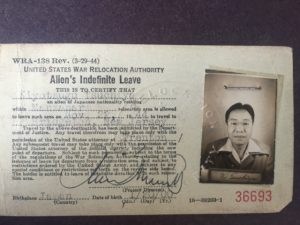

Alien’s Indefinite Leave card allowing Tsuchiya to travel to New Jersey for work in 1944. (Photo courtesy Lourdes Nicholls)

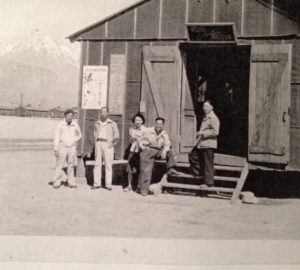

The couple were detained in the Manzanar internment camp for three years with 11,000 other Japanese. On a desolate plateau, the hastily built camp was surrounded by barbed wire. Armed guards patrolled the watchtowers. A total of 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of them American citizens, evacuated to internment camps. Daughter Fumi was born in Manzanar.

Based on his experience as a curator, camp directors asked Tsuchiya to create a museum for the camp, which he did. At first the museum consisted of collected animals, insects, plants and found objects. A best friend, Toyo Miyatake, smuggled a camera into the camp and recorded life there, later publishing a book. When WPA photographer Ansel Adams arrived to photograph the camp, he befriended Miyatake and Tsuchiya. Adams also allowed the camp museum to later host a display of his photos.

After being freed from the camp in 1944, Tsuchiya worked briefly in Chicago and New Jersey at a hotel, a plaster casting business and a cannery, earning less than $1 a day. He eventually was hired by Oklahoma University to teach Japanese and helped as a translator during post-war criminal trials in Japan.

Meanwhile in Chicago, Harding’s daughter and some former associates sued the museum and Katz in the 1940s. The museum continued through the 1960s, when it closed and the building was demolished in an urban renewal street-widening program. The collection ended up downtown, available for viewing only by appointment. When a batch of antique musical instruments was intercepted en route to an auction house, lawyers for the Illinois Attorney General accused the collection’s trustees, former lawyers of Harding’s daughter, of conspiring to sell pieces of the collection. Directors were paid “exorbitant” salaries and $250,000 was used to buy shares in a bank, prosecutors charged.

During his lifetime, Harding is said to have wanted the collection to end up at the Art Institute. At the time it was turned over as part of a legal settlement, the collection was reputedly valued at $25 million.

Tavares is the most recent link in a chain of curators, leading back to Tsuchiya.

Curator Leonid Tarassuk, had also been displaced for political reasons as former “Keeper of Western Arms” at the Hermitage Museum in Moscow in the Soviet Union. According to his 1990 New York Times obituary, Tarassuk was imprisoned from 1959 to 1962 “what were called anti-Soviet activities, because of comments he made in a private residence that was bugged.”

Tarassuk was tasked with unpacking crates of artifacts after the collection was delivered to the Art Institute, in the early ’80s, Tavares said.

“It must have been a tough job because there was very little paperwork,” Tavares said.

Tarassuk identified some pieces that even Harding may not have known about, such as a 1610 hunting pistol belonging to Louis XIII of France and a breast and back plate from body armor created for “False Dmitry,” Tsar of Russia for less than a year in 1605-1606, Tavares said.

After Tarassuk’s death, Walter C. Karcheski curated the collection next, writing a book about it that Tavares remembers receiving as a Christmas gift at age 15.

“To actually be the curator of this very collection is like childhood dream come true,” Tavares said.

Tavares gathered an opening night party for the new exhibit inviting Nicholls and her mother Knox. Also attending were descendants of the Harding clan and a retired assistant AG who helped move the collection to the Art Institute.

“I do believe in fate, and it was fate that brought this collection to the Art Institute and that brought Lourdes with the scrapbooks from her grandfather,” Tavares said.

Kyotsugu Tsuchiya became a U.S. citizen in 1955. In 1990, he was one of the first internees to be issued a $20,000 reparations check from the U.S. government for wrongful internment and loss of property. But the check arrived a few months after his death.

For Nicholls, bringing her mother to see the Harding collection in all its glory was a “bucket list” event, she said. She hopes to write a book or maybe use recordings of her grandfather’s stories to create a documentary about his life journey.

“It has been a rollercoaster of emotions but I feel like my grandfather would be proud,” she wrote. “It’s ironic that two years after [my grandfather] left one of the most amazing/priceless museums he would be the curator of a museum in an internment camp collecting bugs, butterflies and household items.”

Read the current issue of the Cook County Chronicle

Free subscription to the digital edition of the Cook County Chronicle

— New Art Institute exhibit includes WWII internment camp for first curator —