New hall of fame to celebrate Chicago’s rich musical heritage

By Bill Dwyer For Chronicle Media — October 5, 2017

The Chicago Music Hall of Fame museum will be located in the top three floors of a four-story building at 1431 Taylor Street that now houses the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame.

Ron Onesti, a veteran Chicago area cultural and musical events promotor, has announced plans to launch a Chicago Music Hall of Fame late next year.

Onesti, who brings national music acts to his 900-seat Arcada Theater in St. Charles, envisions a video centered museum honoring and celebrating the many personalities and bands that have enriched Chicago’s music scene over the last century. He says he’ll invest about $250,000 into lights, sound and video for the music museum space, which he hopes to have ready for the public within the next 12 months.

The museum will be located in the top three floors of a four-story building at 1431 Taylor Street that now houses the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame. The sport hall will consolidate its daily operations and exhibits on the first floor. Onesti said the music hall will be centered on the second floor, with food, beverage and entertainment options located throughout the rest of the upper two floors.

Onesti, who calls Chicago’s influence on the development of popular music “almost immeasurable,” will have a deep well of talent and musical experience from which to draw. The museum will focus on music from 1920s jazz and the big band era through the Mississippi Delta Blues that took northern root on Chicago’s southside, and on to the rock and pop scenes that music helped spawn. In addition, Onesti wants to spotlight the venues in which all that music happened, and the behind-the-scenes players responsible for promoting the music.

“There is so much to feature,” Onesti said.

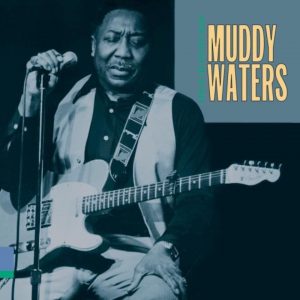

Chicago’s place in American music is well established. The city was becoming a hotbed of jazz when what is now called the great migration began around 1915. Between then and the early ’60s, around 6 million African Americans fled the racial oppression of the Deep South in an historic exodus. Hundreds of thousands of them came to Chicago, and with them a rich lode of musical tradition and talent, including Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf and numerous others.

The city is dotted with musically significant sites, many just a few miles from the proposed museum.

One of the first things a then-unknown English band called the Rolling Stones did after their first album was released in June 1964, was come to Chicago on a tour break and record at the legendary Chess Studios at 2120 South Michigan Avenue.

Stones guitarist Keith Richards has called the Chess studio “hallowed ground.” It certainly was fertile ground.

The incomparable Muddy Waters, born McKinley Morgenfield, made Chicago his home for nearly 50 years, and made his adopted town a mecca for many rock superstars who idolized him.

Waters recorded his powerhouse “Mannish Boy” at Chess; Chuck Berry laid down “Johnny B. Goode” there. And when Fontella Bass recorded her pop/soul classic “Rescue Me” in August, 1965, her session musicians included drummer Maurice White and bassist Louis Satterfield, who went on to form Earth, Wind & Fire.

Many of the songs recorded at Chess were penned by song writer Willie Dixon, who heavily influenced the likes of the Stones, Cream, and Led Zeppelin.

The Pilgrim Baptist Church, at 3301 S. Indiana Ave., is widely believed to be the birth place of modern gospel music under composer Thomas Dorsey.

BB King, Chuck Berry and Waters were just a few of the blues greats who played the Checkerboard Lounge on 43rd Street, where numerous white blues aficionados like Richards and Mick Jagger and guitarist Eric Clapton came to pay homage to their idols.

When the Beatles and the Stones led a so-called British Invasion in the mid-’60s, Chicago radio exploded with an incredible array of music. White youth all over the Chicago area were electrified by music largely sourced from those African-American blues pioneers. By the mid-’60s there were hundreds of garage bands playing gyms and teen clubs across northern Illinois.

The best of those bands joined a host of national acts playing at numerous clubs around the Chicago area. That all culminated in perhaps the heyday of Chicago popular music between 1967-68, when Chicago area bands like the Shadows of Knight, The Buckinghams, New Colony Six, Cryan’ Shames and American Breed had numerous hit songs played on Chicago radio stations WLS and WCFL.

Guitarist Mimi Betinis was one of those kids who fell in love with British Invasion music while growing up in Oak Park. He formed Pez Band following high school graduation with drummer Mick Rain, guitarist John Pazdan and bassist Mike Gorman. They added singer Cliff Johnson in 1972.

Johnson left the band in 1974 and eventually formed the popular but short-lived Off Broadway, which recorded three albums. Meanwhile, Pez Band, which started out playing covers of Peter Green era Fleetwood Mac, was by 1978 opening major stadium shows for Fleetwood Mac, as well as Supertramp, and playing top clubs like Max’s Kansas City and CBGB’s.

The Buckinghams, from Chicago’s Northwest Side, had five hits between 1967 and 1968, including the million-selling “Kind of a Drag.” They were among a half dozen top bands in the Chicago radio market round that time.

Though officially disbanded in 1980, Pez Band continued to play on and off, including in England in 2006-07, and more recently in Japan, where they still have an ardent fan base.

Asked what he thought of the proposed local music hall of fame, Betinis said he would be “very honored” to be included.

“We were so fortunate to have grown up in a time when the origination of contemporary art and music was the norm and that is what influenced me the most,” Betinis said.

Few people around today have a stronger institutional memory of the history of popular music in Chicago than Bob Sirott. The DJ and television personality says it’s about time the city honored its rich and varied musical history.

“It’s a shame that Chicago does not really have an official home that tells the story of the impact this city has had on the international music scene,” Sirott said. “We are finally going to have a place that will celebrate these contributions, and I am excited to be a part of it.”

Onesti said that while he envisions a hall of fame for the Chicago music scene, he doesn’t see a traditional hall of fame process, with annual inductions of a few artists stretching out over many years.

“I want this to be a living, breathing exhibit from the start,” Onesti said. “The plan is to include all the stories pertaining to Chicago and its music. I am not going to ‘induct’ five to 10 individuals or groups each year. I want as many of the pioneers to be ‘inducted’ right now, not over the next 20 years.”

Onesti has formed an advisory board that includes Sirott and other radio and television personalities and music industry professionals. He said he intends to build both an online and on-site presence “almost immediately.” That includes promotional and fundraising events, with a goal of completing the hall of fame’s main exhibits within the next year.

Onesti’s project received a warm welcome from prominent Taylor Street businessman George Randazzo. The president and founder of The National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame said the music museum will complete the vision he had for Taylor Street 20 years ago.

“To have (Onesti) adding an entertainment element to our building and to Taylor Street will be a huge boost for us and to the community in general,” Randazzo said. “Our original intention was to create a complete entertainment experience here on Taylor Street and this is the piece of the puzzle that will help accomplish that.”

Free subscription to the digital edition of the Cook County Chronicle

Read the current issue of the Cook County Chronicle

— New hall of fame to celebrate Chicago’s rich musical heritage —