Westmont honors soldier hero of ‘Hell’s Perimeter’

By Bill Dwyer for Chronicle Media — September 5, 2019

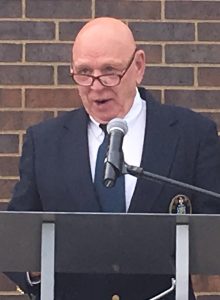

Vietnam veteran Phil Hall, a Charlie Company comrade of James Robinson, speaks at the ceremony August 30, renaming the Westmont Post Office in Robinson’s honor. (Photo by Bill Dwyer / For Chronicle Media)

Aug. 29 would have been Westmont native James W. Robinson Jr.’s 79th birthday.

The occasion was observed as family, friends, admirers and various public officials gathered at the Westmont Post Office to celebrate its renaming as The James William Robinson Memorial Post Office Building.

Most people driving past the Cass Ave. building won’t know the man behind that name, the life lived or the long-ago deeds underlying the honor bestowed.

Phil Hall knows the name and the man.

He was there that terrible day in a terror-filled jungle battle field in Vietnam during Operation Abilene. In April 1966 when James W. Robinson Jr.’s heroism gave him and 27 other men a chance to survive the night.

Combat soldiers call it “foxhole adoration,” the respect and trust one warrior puts in another knowing the man has what it takes to handle the terror and chaos of a firefight.

Robinson certainly did. Wounded at least three times, out of ammo for his rifle and watching his comrades being shot up by withering .50 caliber machine gun and sniper fire, he refused to stay in safe cover.

At 6-2 and 210 pounds, the former US Marine who earned a karate black belt while serving on Okinawa, had already served his time. But he re-enlisted in the Army because he wanted to join the fight in Vietnam. On April 11, the fight found him during one of the most vicious fire fights of the entire war.

Operation Abilene near the village of Xa Cam My, 40 miles east of Saigon, was supposed to be a battalion-sized search and destroy operation with Charlie and two sister companies hunting an elite Viet Cong battalion.

“We were looking for a large front line battalion,” said Hall.

But only Charlie Company made contact. Nearly 300 men strong on paper, it was down to 134 soldiers due to of various reasons including injury and leave. The company’s four platoons were supposed to be backed by two other companies, but military planners did not account for the time and effort required to hack through dense jungle foliage.

It was later determined that Bravo Company was just 1,000 meters away when Charlie Company was attacked. But jungle vegetation so dense soldiers “often lost sight of the man nearest him,” had limited their forward progress to about 100 meters an hour.

“You were lucky to see 15 to 20 meters away,” Hall said. “What went wrong is that both our sister companies couldn’t get to us in time to lessen the casualty rate.”

What resulted was an utter debacle, with 80 percent of Charlie Company killed or wounded. Hall himself was wounded and knocked unconscious twice, first by a mortar explosion then later by a grenade.

The descriptions below are from Phil Hall’s recollections, James Robinson’s Medal of Honor citation, a newspaper account, The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War and journalist George Wilson’s well researched narrative of the battle in his 1989 book “Mud Soldiers.”

Hall said it all started when three Viet Cong wandered into a clearing nearby.

”Several soldiers formed a firing line, and we hit all three of them,” he said. “One got away wounded.”

Within minutes, Charlie Company was getting hit with a hail of sniper fire from distant trees. “They were hit with mortars, recoilless rifles and small arms fire after part of the probe killed five members of a Viet Cong platoon in a brisk fight,” one newspaper account read.

What followed was anything but “brisk.” According to The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, an official Vietnamese Communist unit history stated that all three battalions of the VC 4th Regiment/5th Division joined in the assault on Charlie Company that afternoon.

“They were waiting and ready for us,” said Hall. “What we walked into is called a ‘kill sack.’ They set up a horseshoe perimeter, and they let you get all the way in, and they close the door.”

Plaque honoring the late James W. Robinson Jr. on the wall of the U.S. Post Office in Westmont. (Photo by Bill Dwyer/for Chronicle Media)

Charlie company’s four platoons quickly “circled the wagons,” into a defensive circular perimeter utilizing “interlocking fire.” But the hunter had become prey. Pinned down, the soldiers were shielded from the mortar explosions, but not from numerous snipers firing from the trees.

“Lying flat, the soldiers were protected against mortar fragments, but not against the Viet Cong snipers high in the trees,” Wilson wrote. “They kept getting shot in the back as they lay prone.”

Around 3:45 p.m., engineers managed to cut a hole in the jungle canopy to allow Air Force para-rescue troopers to rappel down to the jungle floor. One by one, 12 wounded men were winched up in a basket to a HH-43 Huskie helicopter.

As the chopper flew away, all hell broke loose. Around 5:45 p.m. two .50 caliber and eight .30 caliber machine guns encircling Charlie Company opened up. The 50s calibers were devastating – within minutes more than a dozen more men were killed or wounded. Despite repeated attempts to break out of the trap, Charlie Company remained pinned down.

“I kind of viewed it as possible no one was going to get out of this,” Hall said, adding, “I was going to go down fighting.”

It was indeed “Hell’s Perimeter.” A newspaper article the next day spoke of the cries of dying soldiers. “I’ve never heard such screaming in my life,” one soldier is quoted. “Many of the wounded were yelling for their mothers. Some of the kids were calling for God.”

Hall recalled one young soldier he knew, lying mortally wounded outside the perimeter. “He was hurt so bad, he cried out for someone to shoot him.”

As the night wore on, Hall said, the cries became” fainter and fainter.”

Robinson, already wounded twice, was cursing at the devil, “spraying M16 fire at the trees, killing snipers, one of them with an M79 grenade launcher.”

“As the battle continued and casualties mounted, Sgt. Robinson moved about under intense fire to collect from the wounded their weapons and ammunition and redistribute them to able-bodied soldiers,” his citation reads.

Wilson wrote that Robinson, “saw a medic and a sergeant, both wounded and pinned down by enemy fire. Running through bullets, he locked one man in each arm, dragged them inside the perimeter, dressed their wounds, gave them shots of morphine.”

“One of his buddies had been cut down by machine-gun fire. Robinson ran to him. The same machine gun hit Robinson’s leg as he ran. He reached his comrade, pushed him behind a tree, tied bandages around the worst wounds and patched himself as best as he could under cover of the tree.”

It was then that Robinson made the decision to risk what his Medal of Honor citation called “an act of unsurpassed heroism.”

“‘I’m going for it! Cover me!’ he told his colleagues. But he was out of ammo, so, “sitting beside the wounded man, he pulled two grenades off his web belt. He yanked out the pins so they were ready to go off once he let his fingers off the firing mechanism.”

Robinson charged the machine gun with a grenade in each hand. “A tracer round hit him in the leg, setting his trousers on fire,” Wilson wrote. “He staggered to within 10 yards of the gun and lofted the grenades expertly into the position. They went off in one giant blast, killing the crew and silencing the .50 for the rest of the battle.”

With that, Robinson, hit in the chest by two more 50 caliber slugs, fell dead.

Hall didn’t see Robinson fall, but he and what was left of his platoon felt the effects of his actions immediately. More likely than not, they all lived because Robinson took out the gun nest.

“There’s no question that taking out that 50 caliber saved lives,” Hall said.

There was more suffering, fear and sheer endurance before the night was over and help arrived.

“It was a long night,” Hall recalled. He noted that the Army dropped “1,143 (105 mm) cannon rounds as close as 15 meters (less than 50 feet) from his position (at the request of the company commander) to fight off the Viet Cong.

The after-action report estimated that at least 150 elite North Vietnamese troops had been killed. But the survivors of the Battle of Courtenay Plantation had no interest in any reports. Of the 134 men who walked into the jungle, 36 were dead and 71 badly wounded.

Medal of Honor citations don’t speak of emotion, but Wilson’s reporting noted that most of Charlie Company’s 27 survivors “cried unashamedly” as they viewed the carnage in the morning light.

Hall said any thoughts of politics or patriotism didn’t matter that day, only the brother’s in arms around you.

“I never thought of winning one for the Gipper,” Hall said. “You fight for your brother and for life itself. You fought or you died.”

James Robinson Jr. fought for his brothers that night, and those who recall him do not want him or his deeds forgotten.

In a way, our families are his family, our kids are his kids,” Hall told the Chronicle.

Last Friday afternoon at the ceremony honoring his fallen comrade, Hall spoke again of the great and precious gift Robinson left his fellow soldiers.

“Those of us who survived that day, and Vietnam… came home and had the rest of our life,” he told the audience. “Sgt. Robinson didn’t get to have the rest of his life. He didn’t get to have that Mustang convertible. He didn’t get to have kids and grandkids.”

“He gave that to us.”