History holds model for effective regional rapid transit system

Bill Dwyer for Chronicle Media — December 29, 2015 Efficient, green intra-city rail was junked nearly six decades ago

Efficient, green intra-city rail was junked nearly six decades ago

In 1957, an editorial in the Chicago Tribune foreshadowed a debate over the appropriate balance between roads and rails in our regional transportation system.

”In some future legislative session there will be [lawmakers] capable of seeing that transportation in a large city cannot depend on the private automobile.”

However, over the next 50 years, most state and federal planners would be largely blind to the positive role rail-based rapid transit played in the Chicago region’s transportation system. This despite the example of a time-tested, relatively inexpensive and efficient rail-based rapid transit technology that was in place for half a century and which had worked just fine.

As modern planners work on the rebuild of the antiquated I-290 Eisenhower Expressway and large scale improvements to the CTA Blue Line that runs along the expressway’s right of way, they would do well to revisit a model that was unceremoniously junked in favor of superhighways, which were once seen as the wave of the future.

Part of that answer those officials seek could literally send them “back to the future.”

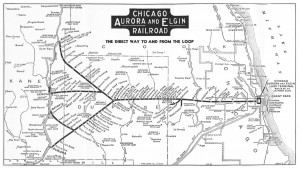

Up until July 3, 1957, the Des Plaines Avenue station in Forest Park was a transfer point where riders on the Chicago, Aurora and Elgin railroad (CA&E) connected with CTA trains heading downtown to Chicago. For half a century the electric CA&E trains transported thousands of riders comfortably and quickly over the Garfield Park Elevated tracks at speeds of up to 75 mph, from downtown Chicago to Forest Park, then on to Westchester, Broadview, Maywood and points as far west as Wheaton, Aurora.

The CA&E’s electric rails were powered by fixed location generating plants, now known to be far less polluting than thousands of individual internal combustion motors.

But February, 1952 saw the beginning of the end of that system, as plans were announced for the extension of the Congress Street Super Highway 30 miles west, through Du Page into then-distant Kane County. That March, a Tribune article predicted that, “Super Highways may strangle Aurora-Elgin.”

The CTA sold its right-of-way for its tracks between Racine Avenue and Sacramento Boulevard in 1952, setting the stage for the destruction of its elevated structure as part of the planned expressway.

In April 1952, the CTA proposed the extension of the CA&E rail service to Oak Park, Forest Park and possibly to Maywood at First Avenue, foreshadowing proposals that would be made 50 years later.

CTA chairman Ralph Budd said at the time that the longer service would permit retention of the CA&E’s electric interurban service. The railroad’s general counsel, Joseph T. Zoline, called the CTA’s proposal “the most intelligent suggestion” thus far for maintaining the existing rails.

However, money was always the determining factor, and most people believed that cars, not trains, were the wave of the future; the money needed to support the CTA’s plans was never appropriated.

In December 1952, the CA&E concluded its presentation before the Illinois Commerce Commission seeking to permanently abandon its rail line west of Wheaton and temporarily abandon its line east of Wheaton. A nearly five-year court fight then began to keep the service going.

Officials at all levels of government attempted to intervene, hoping to work out a deal that would save the rail service, but none succeeded.

The situation became even more problematic when Cook County later went to court to condemn the right-of-way it controlled between Austin Boulevard and the Des Plaines River. The city of Chicago had plans to eventually build the Garfield elevated rail system in the middle of the planned expressway, then allow the CA&E to transfer service to those rails.

But again, no money was committed to the project, and the privately owned railroad’s board of directors balked at the massive losses the likely years-long delay would cost. The CA&E board asked for $3 million to compensate them for their losses but was turned down.

As is still true today, there were large sums for highways in 1957, and much less for rapid transit. In June 1957, Illinois lawmakers approved the appropriation of nearly $645 million over two years for highways, but overwhelmingly rejected a bill that would have allowed the state, counties and cities to use gas tax funds to support rapid transit needs.

That additional tax revenue would have allowed the CTA to purchase the CA&E outright for $9 million. Also, the CTA was seeking around $20 million annually for 15 years to pay for badly needed track and car improvements and to extend the line.

“There may have been sound arguments against subsidizing mass transit with gas tax funds, but none was presented in the house debate,” the Chicago Tribune reported at the time.

The Tribune rather bluntly questioned the legislature’s wisdom in a June 22, 1957, editorial. Noting the massive imbalance between funding of roads and rails, the Tribune called the decision a blow to the CTA, and, “More especially, it was a blow to the people of Chicago and its suburbs.”

At noon on July 3, 1957, after numerous injunctions and challenges and ongoing financial losses, the CA&E pulled the switch on its commuter service-unbeknownst to some 3,500 to 6,000 commuters who’d traveled downtown on CA&E trains earlier that morning. Making matters worse, railroad officials reportedly didn’t notify CTA officials of the shutdown until 5 p.m.

Commuters were met by a posted notice and an apologetic station master. Officials at the Leyden Motor Coach company, which was planning to pick up the slack when the CA&E eventually ended service, were also caught unprepared.

The West Town Bus Company in Oak Park sent four buses to transport people to train stations in River Forest and Elmhurst. Some commuters took cabs, if they could get one, or called home to arrange for a car to pick them up.

Wheaton resident Julie Johnson, who was 15 at the time, was one of the earlier arrivals who was able to hail a cab to Oak Park and catch a train home. But for thousands of other commuters arriving later that afternoon, their previously routine trip had suddenly turned into a mob scene, as trainload after trainload of returning commuters arrived to find the last leg of their journey home no longer existed.

“They just said, ‘We’re sorry, but the railroad’s been shut down,’” Johnson recalled several years ago.

By 5 p.m. an estimated 3,500 riders had arrived at the station, and things took an ugly turn as more and more people realized they were stranded. There were reports of benches and other equipment being thrown onto the tracks by angry commuters.

Nearly three years after the CA&E made its final commuter run, permanent Congress Line service on the Eisenhower Expressway (now the Blue Line) began in March 1960 between downtown and the city limits at Austin Boulevard. Tracks were also laid in the Oak Park section between Austin and out to Des Plaines Avenue in Forest Park.

On Oct. 12, 1960, the last three miles of expressway, between Austin and Des Plaines Avenue, opened for traffic. But any chance that the CA&E model could have been resurrected died in 1961, when the entire length of the CA&E tracks west of Forest Park was abandoned without ceremony.

The right-of-way eventually gave way to various housing developments and the Illinois Prairie Path.

In the 58 years since the CA&E ceased service, cars have increasingly been the primary mode of travel connecting the far western suburbs to downtown, to the detriment of the environment and the built up communities through which the expressway moves some 200,000 vehicles daily.

That may now finally be changing, as Oak Park and other west suburban communities have come to realize that they’re getting swamped by “the wave of the future” and its ever-increasing environmental impacts.

–History holds model for effective regional rapid transit–