Underwood, Kennedy speak out for better mental health care

By Erika Wurst For Chronicle Media — August 2, 2019

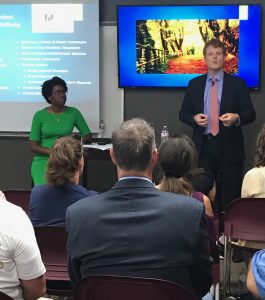

U.S. Rep. Lauren Underwood of Naperville listens as fellow Democrat Congressman Joe Kennedy III speaks about the need for elevating the status of mental health care during a forum at the Kendall County Health Department on July 31. (Photo by Erika Wurst/for Chronicle Media)

In a small, but jam-packed room inside the Kendall County Health Department in Yorkville on July 31, you could hear stigmas being broken.

You could feel shame flying out the window and listen as once silent voices were being raised.

The voices were those of young men and women who were sharing their plights with mental illness at the Generation Z/Millennial Mental Health Forum.

They had come to meet with Congresswoman Lauren Underwood (D-14th) of Naperville and Massachusetts Congressman Joe Kennedy III, a fellow Democrat, to discuss the problems they’ve faced, and to seek help for mental health advocacy.

“My hope here is to hear your voices and elevate your stories,” Kennedy told the crowd. “There are people at every level fighting for you and we can only do that if you raise your voices and partner with us so we can help.”

Bravely, nervously, and ready to see changes be made, several young men and women got up in front of the sea of faces to share their stories. While each story was unique, all of them had a common thread.

Each speaker expressed the need for access to mental health care.

There was Emily, 26, who lives in Aurora. She obtained a master’s degree, owns her own business, and is now living life to the fullest. Ten years ago, that wasn’t the case.

Emily had tried to take her life on many occasions. Her drive for perfection drove her to the edge and it would take several hospital stays before she got back her will to live.

During her last attempt, where she overdosed on the bus during a band trip home from Disney World, Emily wasn’t sure she’d make it out alive. She promised herself that if she did, she’d do everything to beat her demons.

“I thought in that moment, ‘Oh crap! I don’t really want to die. I want to feel better. I don’t want to feel nothing every again.’,” she professed.

With a new attitude, and proper mental health care, Emily has learned to take care of her mental illness and succeed. Her hope is that the access to care that she was afforded will one day be afforded to everyone.

“I live a totally normal life now. I am not the ‘normal’ picture of someone with mental illness,” she said. “But, without help, I don’t know who I would have become. If (those incarcerated or the homeless) had the treatment they needed, who would they be? If we went to the root of the problem, I’m willing to be a lot of times their issues have to do with mental illness. If we had treatment for them, think about who we could be as a community?”

U.S. Rep. Joe Kennedy III addresses the audience gathered July 31 for the Generation Z/Millennial Mental Health Forum held at the Kendall County Health Department in Yorkville. (Photo by Erika Wurst/for Chronicle Media)

Younger students, still in college, lamented about their access to care within their universities— sometimes waiting up to four months to get in to see a mental health provider.

Kennedy supported their concerns.

“Would you ever tell someone with stage 3 Cancer to come back in four months and see you then? If we ever tried that, the outrage would be immediate and we’d fix the system,” he said. “Twenty percent of Americans are going to be diagnosed with a metal illness at some stage in their life. This is not a rare thing, and the system is not set up at all to deal with these issues. This system needs a massive structural overhaul.”

Those without proper access to therapy and medications are often found self-medicating, Underwood pointed out.

“This can be deadly,” she said. “It is in our community’s best interest that people who need access to medication get medication.”

For those like Emily, who shared her story, Underwood’s response is one she sought to hear.

“This is so important to treat, talk about, and not be ashamed of,” she said.