BICENTENNIAL 2018: Lincoln the first president to make use of electronic mass media

By Steve Tarter — August 9, 2018FDR used the radio, JFK scored on TV and Donald Trump embraces Twitter. But the first president to make effective use of electronic communications was Abraham Lincoln.

His use of the telegraph, a tool used extensively during the Civil War, was one of the things that made Lincoln a unique communicator in tumultuous times.

“Two things set Lincoln apart in terms of his relationship with, and mastery of, the press,” said Harold Holzer, author of “Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion,” published in 2015. “His language was simple and direct enough to make press reprints of his speeches especially compelling. Second, he courted journalists from the beginning of his career.”

Holzer, director of the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College in New York City, added two more things: “(Lincoln) drafted editorials for his Whig and Republican newspapers and owned a newspaper, himself (as did his arch-rival, Stephen A. Douglas),” he said.

The newspaper that Lincoln purchased — in secret — was a pro-Republican, German-language paper published in Springfield just prior to the 1860 presidential election. “State legislators bought and distributed the paper in their districts,” said James Cornelius, curator of the Lincoln Collection at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum in Springfield.

Cornelius said Lincoln’s rise in Illinois politics was marked by a close relationship with the press. “He was often in newspaper offices up and down the state in the 1830s and 1840s. Hanging around a newspaper office was a good place to shoot the breeze — and exchange information. He also wrote a lot that was published anonymously during that time,” he said.

William Herndon, Lincoln’s Springfield law partner, observed Lincoln’s relationship with the press firsthand. Writing in 1886, he noted: “In common with other politicians, he never overlooked a newspaperman who had it in his power to say a good or bad thing of him. The press of that day was not so powerful an institution as now, but ambitious politicians courted the favor of a newspaperman with as much zeal as the same class of men have done in latter days.”

Herndon recalled Lincoln writing to an editor of a small country paper in southern Illinois. “‘I have been reading your paper for three or four years and have paid you nothing for it,’ Lincoln wrote. He then encloses $10 and admonishes the editor with innocent complacency: ‘Put it into your pocket, saying nothing further about it,'” he said.

Not long after, Lincoln sent an article “on political matters” to the editor – who declined to publish the piece “because I long ago made it a rule to publish nothing as editorial matter not written by myself.”

“Although the laugh was on Lincoln, he enjoyed the joke heartily,” noted Herndon, recalling Lincoln saying, “That editor has a rather lofty but proper conception of true journalism.”

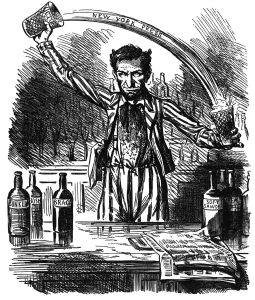

True journalism wasn’t always on display in the newspapers that reigned in Lincoln’s era. Editors were not shy about taking stands — or taking shots — at the nation’s leaders.

“Let’s just say that the openly, proudly partisan editors of the Lincoln era — Republicans like Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune and Democrats like Manton Marble of the New York World — would not be surprised at all that today’s media outlets, like Fox and MSNBC, display the same kind of doctrinaire leanings, except (the networks of the 21st century) don’t like to admit it,” said Holzer.

“Partisanship was deeply embedded in the American press tradition, from the days of John Adams onward,” he said.

In talking about the “reliability” of newspapers, Lincoln is said to have joked, “They lie and then they re-lie.” But Lincoln also said, “No man, whether he be private citizen or President of the United States, can successfully carry on a controversy with a great newspaper, and escape destruction unless he owns a newspaper equally great, with a circulation of the same neighborhood.”

Lincoln learned how to deal with a divided press just as he did with a divided country. “Mr. Lincoln understood the power of the press. He well understood the excesses of the media, especially during his presidency. On the whole, he was thick-skinned, but he did object to falsehoods, calumnies, libel and slander,” noted Lewis Lehrman, author of “Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point.”

“Lincoln’s genius with the press consisted primarily in presenting arguments for the Union cause and emancipation which prevailed over the common prejudices of the day. His fair-mindedness, even in the face of vicious press attacks, was apparent to all — in the end, even to his enemies,” Lehrman said.

Holzer suggested that a lifetime of reading, writing and negotiating with newspapers laid the groundwork for what Lincoln was able to do as president: reach the public with letters to the editor spelling out his positions on some of the much-debated issues of the day.

“With his dramatic letters of 1862 and 1863, Lincoln in some ways wrote the big three New York editors out of the equation when it came to molding public opinion,” the historian noted.

Lincoln’s habit of maintaining close ties with members of the press as president didn’t always set well with members of his Cabinet. Writing in his diary in 1864, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles complained: “It is an infirmity of the President that he permits the little news mongers to come around him and be intimate, and in this he is encouraged by (Secretary of State William) Seward, who does the same, and even courts the corrupt and the vicious, which the President does not. He has great inquisitiveness. Likes to hear all the political gossip as much as Seward. But the President is honest, sincere and confiding — traits which are not so prominent in some by whom he is surrounded.”

When it came to using the technology of the day, Lincoln learned about sending messages by wire from Charles Tinker, a telegraph operator he met at the Tazewell House hotel in Pekin in 1857. By the time he moved to Washington in 1860, Lincoln was well aware of how the telegraph operated and ways he could use it, stated Tom Wheeler, author of “Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War.”

Lincoln not only installed a telegraph office at the White House but used that office as a situation room, allowing the president to communicate with field commanders in the nearest thing to real time that was available in the 1860s, noted Wheeler, adding that Lincoln sent out almost 1,000 telegrams during his time in the executive office.

But speed of transmission wasn’t the only factor that made Lincoln a great communicator. “Lincoln was a master political strategist. He understood what it took to get the message out to people,” said Peter Schnall, a filmmaker whose “Lincoln@Gettysburg” program was shown on PBS in 2013.

The president’s 272-word Gettysburg Address was a good example of adapting his message to the media, Schnall said, “(Lincoln) knew the speech would be telegraphed across the nation; within 48 hours every newspaper as far as California had printed the speech straight on the front page, which is exactly what he was aiming for.”

Steve Tarter covers city and county government for the Journal Star. He can be reached at 309-686-3260 or starter@pjstar.com. Follow him at Twitter@SteveTarter and facebook.com/tartersource.

Editor’s note: The weekly Illinois Bicentennial series is brought to you by the Illinois Associated Press Media Editors and Illinois Press Association. More than 20 newspapers are creating stories about the state’s history, places and key moments in advance of the Bicentennial on Dec. 3, 2018. Stories published up to this date can be found at 200illinois.com.

–BICENTENNIAL 2018: Lincoln the first president to make use of electronic mass media–